Sonic Solitude

Photo by Sammy Sander

Photo by Sammy Sander

Have you ever visited a restaurant and upon leaving found yourself inexplicably in a bad mood? The food and drinks were great; you dined with your favorite friends, whom you usually have such a wonderful time with; yet there seemed to be some sort of invisible force hampering the conversation. Oh, wait, could it be sound? Admittedly, it was a noisy restaurant, but how could that ruin the evening?

According to a study by Consumer Reports, noise is the leading cause of complaints when dining out. Many restaurateurs struggle to control the acoustical problems created as a by-product of ignoring the acoustics in their dining environments. The study shows that people complain more about noise than service, food quality, or an unclean environment.

Sound and noise have an incredible ability to change a person’s mood, affect their judgment, or bring on anxiety, depression, isolation, or exhaustion. Done right, sound can also help a person feel happier and more productive.

Unfortunately, you rarely hear of positive sonic experiences. Few people ever say, “This is a great-sounding room” or “Wow, that space really improved my mood!” Granted, sonic nuances can be subtle to the untrained ear, but sound can reinforce or supplement positive feelings of relaxation or satisfaction. I attribute this to a certain sonic Zen-like state that I refer to as “sonic solitude.” For many people, peace and solitude involve silence or at the very least controlled and ordered sonic experiences.

For example, can anyone deny the beauty of the Kimbell Art Museum’s entry sequence defined sonically on approach by the sound of running water, the subtle crunch of crushed gravel beneath one’s feet, then the transition to the refined and tight sound of feet walking on travertine before entering the building? Louis Kahn was not an acoustician. He did, however, master defining spatial sequences by experience. As architects and creators of place, we should strive to do the same by engaging sensory experiences beyond the visual.

Let’s break those sonic influencers down into three fundamental components.

Reverberation

First is reverberation, which is defined as the accumulation of sound waves after a sound source stops. If controlled, reverberation can enhance the aural perception and spatial definition of musical instruments, voices, or even environmental sounds that define an architectural space and thus the user experience.

On the other end of the spectrum, if uncontrolled, reverberation can completely overwhelm listeners and make basic conversation difficult at best. The aural assault created by reverberation noise is something nearly everyone has experienced at one time or another. Reverberation problems haunt patrons of restaurants, churches, nightclubs, and even school learning environments on a massive scale. To say there is room for improvement would be an understatement.

Here is a voice with no reverberation, courtesy of mcsquared.com. Then listen to these two examples—a voice with just 1.3 seconds of reverberation and a voice with 5.0 seconds of reverberation—to discover how it doesn’t take much uncontrolled reverberation to dramatically affect speech intelligibility. Add a little music to an overly reverberant space, and you’ve created a sonically jumbled mess.

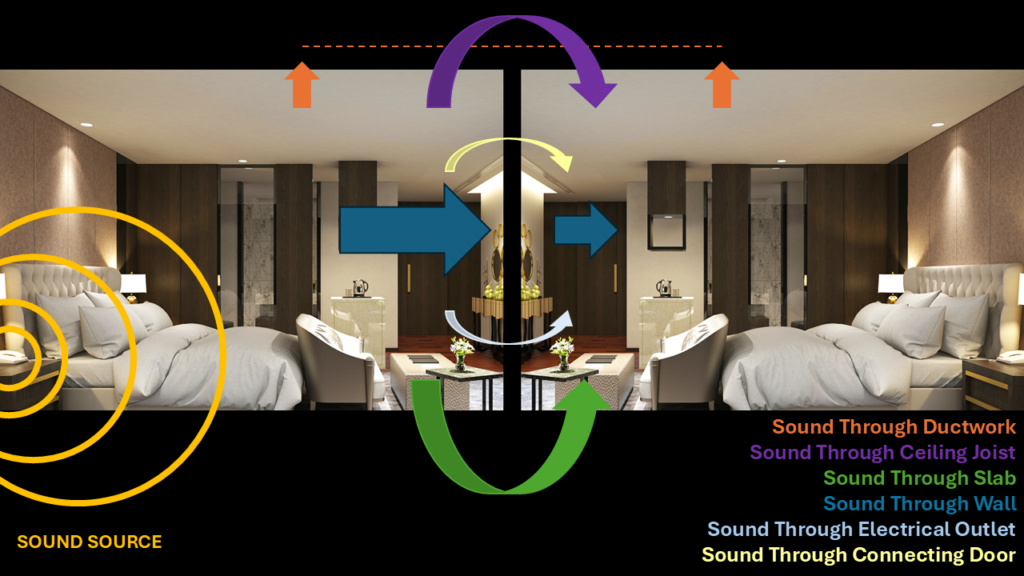

Isolation & Transmission

Isolation is the process of stopping the transfer of sound from one environment to another. Effective isolation prevents sound in one space from infringing sonically into another space (transmission).

The transfer of voices between adjacent cubicles in an office environment is one of the most common isolation/transmission problems. It’s difficult to concentrate when you hear every word your neighbor says. Occupants sometimes try to mask the sound of nearby neighbors with white noise or a sound machine. While this can work for a sleeping baby who just needs to drown out disruptive noises, it typically provides very little benefit in an office environment where people need to communicate with each other.

Likewise, footfall noise caused by individuals walking on hard surfaces intrudes into adjacent spaces; think high heels on a wood or concrete floor in a condominium. Sound transmission can be a difficult anomaly to pinpoint and stop once it has occurred. Best practice is to prevent it from occurring in the first place.

Resonance

The final component is resonance, which is the buildup of sound at specific frequencies. Though less common than the other two components, uncontrolled sonic resonance can be very destructive not only emotionally but also physically. Most people are familiar with the resonance demonstration of a very high singing voice breaking a wineglass. In an architectural capacity, noisy pipes are a common example of sonic resonance. A more destructive example of resonance is when lower frequencies build up in a space to create standing waves with a low resonating hum. It’s almost as if the space becomes a musical instrument—an annoying one. This video provides an excellent visualization of the concept of sonic resonance.

It’s beyond the scope of this article to cover the many possible solutions to these problems, but hopefully this provides an understanding of the fundamentals of architectural acoustical problems, to help you better prepare to work with your acoustical consultants on future projects.

According to acoustician Robin Glosemeyer Petrone of Threshold Acoustics in Chicago, “Most architects don’t want to involve an acoustical consultant until it’s time to choose finishes, but we really can help them much earlier in the design process to solve problems before they occur. A truly successful acoustical design is a process of curation. While deadening a space completely might seem like a successful one-size-fits-all approach, we’ve found that it is not. Different spaces and users have different needs [and …] over-treating spaces causes just as many problems as under-treating spaces. One must remain selective and attuned to the client’s needs. We provide tailored, artistic, and science-backed answers to a project’s biggest questions.”

My message here is simple: Sound plays an important and frequently overlooked role in how people experience architecture. You can either plan for it accordingly or suffer the random outcome of your ignorance. And, much like with other facets of great architecture, not everyone will appreciate or understand your efforts. Regardless, great architects have always taken the higher road with their “a good deed is its own reward” mentality. Whether or not visitors understand the mechanics implemented to create the success is irrelevant; a lasting and positive spatial experience is what’s really important.

I leave you with the words of 19th-century German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, whom I find rather poetic and still appropriate; he said, “Certainly there are people, nay, very many, who will smile at [my predicament], because they are not sensitive to noise; it is precisely these people, however, who are not sensitive to argument, thought, poetry or art, in short, to any kind of intellectual impression: a fact to be assigned to the coarse quality and strong texture of their brain tissues.” One could interpret this quote as implying that the greater a person’s intellect, the less tolerance they have for noise. Shouldn’t we as architects strive for intellectually appropriate spaces that stimulate, not irritate, end-users?

Additional Resources:

A Noisy Restaurant Can Impact Your Food Choices – Even How It Tastes