Dustin Wheat, AIA

Dustin R. Wheat, AIA is a senior lecturer at the University of Texas at Arlington, School of Architecture where he has been teaching since 2009. He served as coordinator of the first-year drawing program for 15 years, playing a pivotal role in shaping the foundational design curriculum. Wheat is an internationally recognized artist, having received multiple awards for excellence in drawing. His work has been featured in publications such as Texas Architect and the RIBA Journal and has been exhibited at the Sir John Soane’s Museum in London. In addition to his academic work, he is a senior designer at BRW Architects, where he brings his artistic insight and technical skills to architectural projects.

How does your role at UTA influence your professional work, and vice versa?

I’d say my professional work influences my teaching more than the other way around. I often share examples of my work, particularly the early stages of design, to show students that the creative process doesn’t have to be polished. That design isn’t a linear process and it’s better to have loose diagrams and gestural sketches that invite interpretation. It’s about questioning and being comfortable not knowing exactly where you’re going.

You have entered the Ken Roberts Memorial Delineation Competition (KRob) and made the show many times. Can you explain that journey?

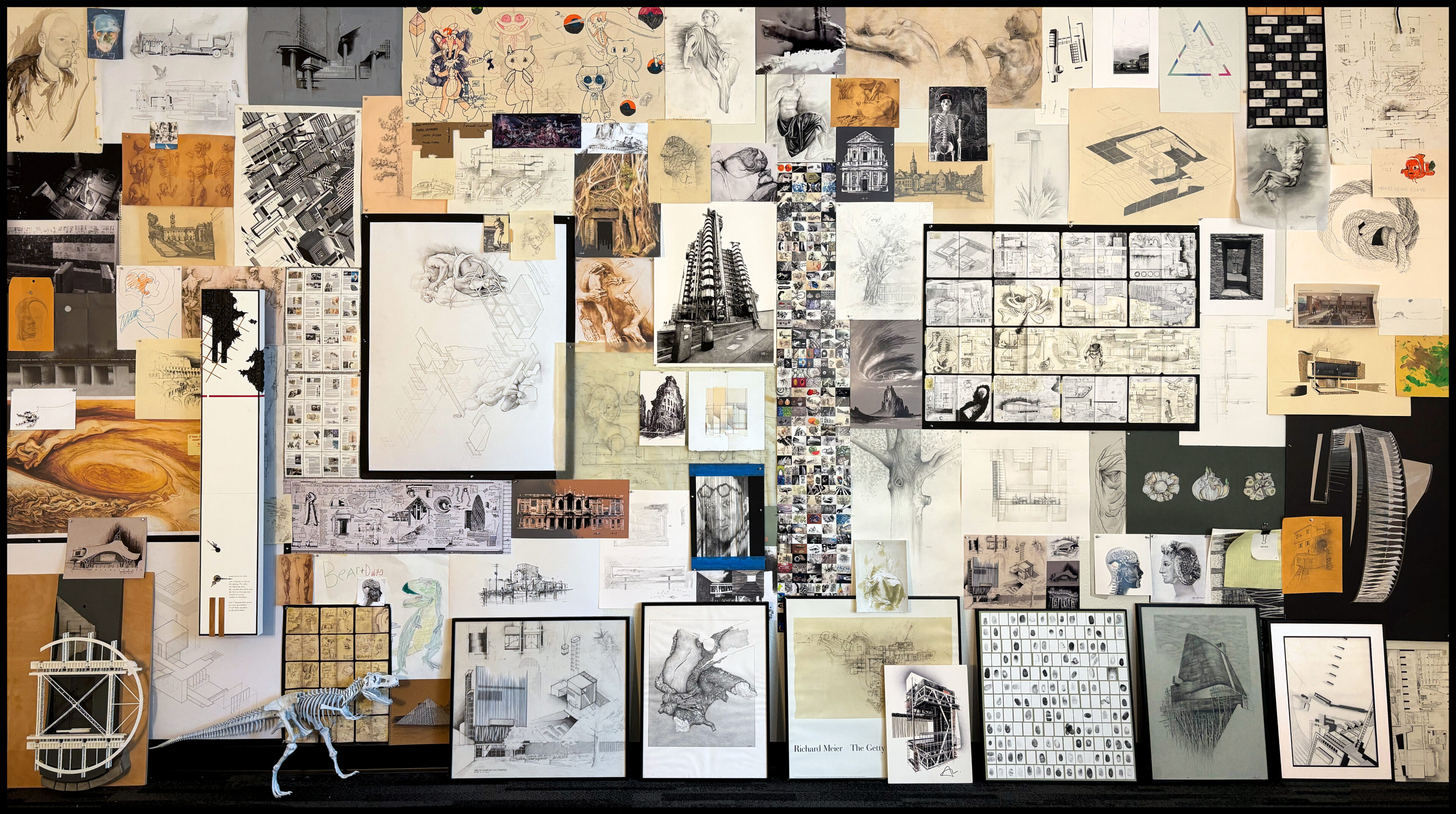

The first time I made the show was in 2007 as a student, that experience gave me a boost of confidence. I chased the competition for the next four years and in 2011, I submitted the dry-erase board which earned my first win. At the time, my mindset was ‘go big or go home.’ The dry-erase board was 48”x144” and took 100+ hours to complete. I was still experimenting with the medium so there was a lot that got erased along the way.

Rather than developing variations of a theme, what keeps me engaged is the process of discovery. In terms of delineation, I’m typically more interested in how something is drawn rather than what is drawn. In general, I choose a medium early on and wait until the right subject reveals itself. In that way it’s a lot like architecture, sometimes we have a compelling idea but have to wait until the right project comes along.

One thing I value most about KRob is the sense of community it fosters. Hundreds of people across 25+ countries come together to exchange perspectives and learn from one another. It’s a rare moment of collective inspiration. Over time, it’s also become a growing resource of creative work for students and professionals to reference.

Your whiteboard drawing was my first exposure to [UTA’s Architecture] program. It inspired me to think that I can draw like that someday.

When I started the whiteboard there was no real plan for how it would come together. My initial concept was to illustrate the range and transformation of architectural drawing. I was also studying for my licensing exams so some of that material naturally seeped in. The whiteboard marked an important moment in my creative path, not just because it was my first professional win, but because it helped me overcome the anxiety of drawing in front of others, as I was still early in my teaching career. It was definitely uncomfortable, but I needed to go through that process.

Are there other competitions that you enter?

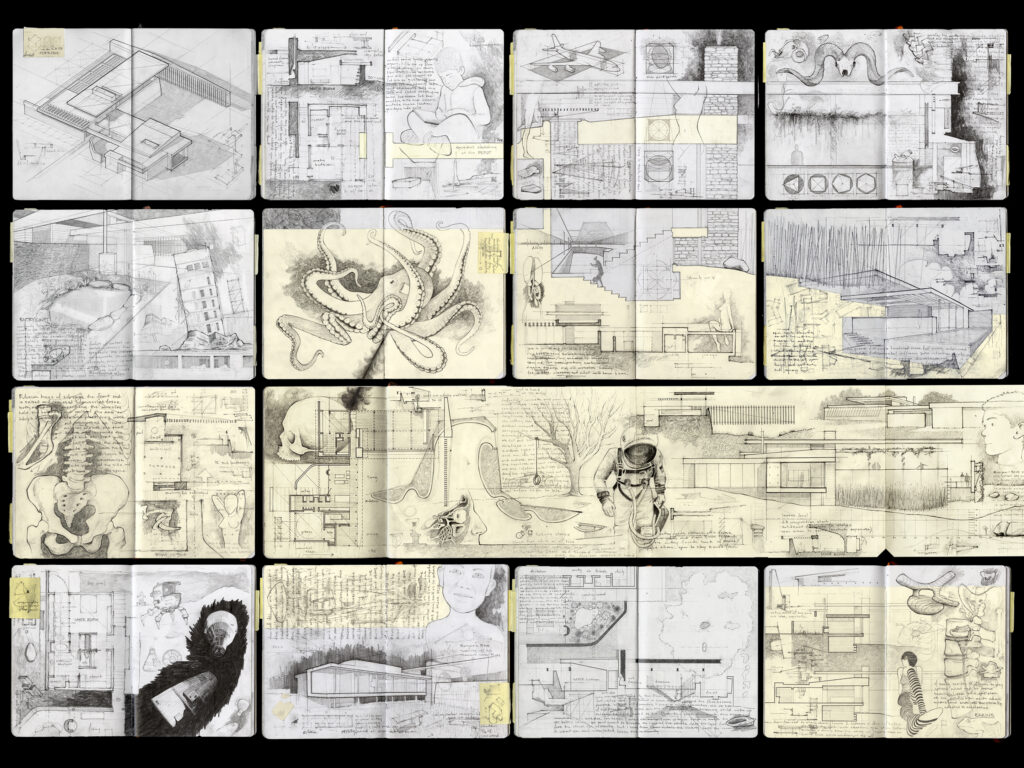

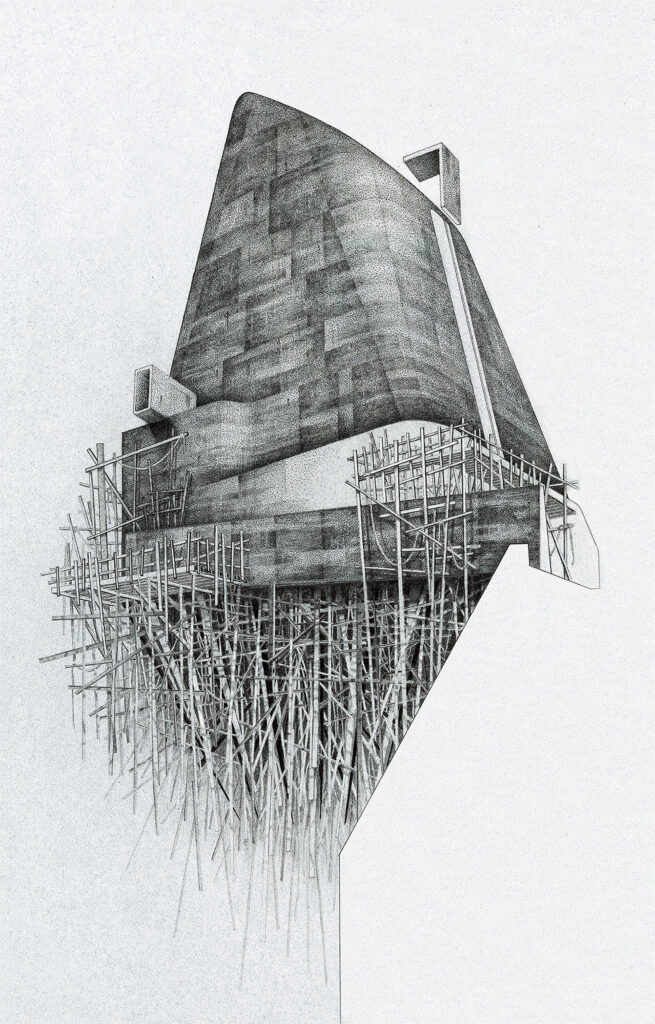

The last competition I entered was the RIBA Journal’s Eye Line, where my sketchbook layout Thinking Architecture was awarded first place. I was also a finalist for The Architecture Drawing Prize, which led to my drawing of Le Corbusier’s Firminy Chapel being exhibited at the Soane Museum for a few months. Seeing my drawing exhibited in London, at the Soane Museum of all places, was surreal and one of the highlights of my career. Every now and then I also enter design competitions, but to be honest, I enjoy the design process more than documenting, so I rarely submit. In fact, I’m still working on a competition that ended last year.

As you work through these pieces and look for a piece of discovery, it leads you to be more process-oriented in your drawing. Would you say that’s accurate?

Definitely. Most drawings that architects do in the professional world are about documentation. We create construction sets to communicate tectonics, perspectives to evoke the feeling of a space, diagrams to illustrate analysis, and so on. But what truly interests me are the kinds of drawings that are often raw, fragmented, and for the most part unresolved. For me, it’s the tracing and retracing of lines that allows my mind to wander, aimlessly at times. It’s the tactility of dragging pencil across paper, the unpredictable shifts in line weight that respond to thought over traditional conventions. It’s as if I’m thinking and not thinking at the same time. Maybe it sounds a bit philosophical, but somewhere in that space between thoughts lies an idea, quietly waiting to be discovered. These drawings are made unselfconsciously, which gives them a very personal quality. They’re the ones that architects cherish yet keep filed away hidden from the client.

You mentioned your morning routine, are you working on a specific piece?

Over the winter break I spent two-weeks traveling Japan sketching temples and gardens. The craftsmanship and inherent beauty of their architecture, not to mention stationery, rejuvenated my love for drawing. Since I’ve been back, my morning routine begins with an hour of sketching. Sometimes I work on competitions, sometimes I start with a line and see where it takes me, and sometimes I try to emulate other drawing styles. Recently, I’ve been re-studying the work of Theodore Kautsky. His first book, Pencil Broadsides, was published in 1940 and has had a lasting impact on how I approach landscape drawing. I’m especially drawn to his greyscale palette, thoughtful compositions, and bold use of contrast. Reproducing his work helps me internalize those techniques and remain connected to his influence.

What do you think you picked up the most from studying other people’s work?

In drawing, you begin to develop your own hand by studying the work of others. The first architectural drawing that truly captivated me was the 1986 preliminary site study of the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. While the site organization was impressive, it was the juxtaposition between the clarity and ambiguity of lines that stood out to me. The drawing embodied the presence of an architect thinking.

Two of my former professors, Richard Ferrier and Kevin Sloan, also had a lasting influence on my understanding of drawing. Ferrier had this beautiful ability to create depth in his lines through subtle variations in pressure. As a student, whenever he sketched over my work, I would spend time copying his lines over and over. Line for line, he was unmatched. Kevin, on the other hand, was a mentor of sorts. While we didn’t work together professionally, he did invite me to collaborate on a 10-foot-long chalkboard drawing for Lark on the Park. For two days I remember being on scaffolding with him and he would talk about the analytical nature of drawing, and then the history of Dallas architecture, and the Renaissance, and Japanese gardens, and so on. His enthusiasm for architecture and breadth of knowledge was astounding.

Outside of professional practice, do you find yourself drawing digitally often?

Yes, mostly with my two boys, affectionately known as the “miniWheats.” My youngest is passionate about 2D animation, so we often set up action figures and a makeshift diorama for him to meticulously photograph frame by frame. It’s a fun collaboration; he brings patience and vision while I provide technical support. My oldest does more digital painting often inspired by Subnautica and Kerbal Space Program. He’s increasingly independent, and to be honest, I might be the one asking him for help before long.

What trends have you seen that interest you or what has really caught your attention as to how academia is professionally or technologically evolving?

At UTA, my role primarily centers on foundational design, which tends to evolve more gradually compared to the upper-level studios. Recently, however, my design studio has been experimenting with integrating AI earlier in the design process, not as a rendering tool, but as a means of generating and expanding ideas. The real challenge isn’t producing a compelling image, most students can do that. The difficulty is learning how to critique an image and pull an architectural idea from it. Once students can frame an argument, we then go through a process that ultimately removes the original AI-generated image, giving students authorship over the final outcome. The process begins with a digital collage, followed by multiple sections cuts. We go through a round of critiques and begin modeling the orthographic sections. As the designs begin to take volume, we introduce spatial narratives and feed that back into AI. We repeat the cycle until something completely unexpected emerges. It’s still an evolving tool and like many others, I’m still navigating its possibilities.

Do you have any advice that you want to pass on to others?

Students often say, “I can see it, I just can’t draw it.” I’ve thought this before and maybe so have you. But if drawing is a way of seeing, then maybe we’re not truly seeing at all. In this context, seeing is to question, with each stroke of the pen becoming part of the answer. It’s a deeply personal process that separates you from me, and both of us from Michelangelo. Consider this: a good musician doesn’t simply play an instrument, they play themselves through the instrument. Drawing is the same, and this is why architects draw, not to perfect the image, but to see and understand the world—and ourselves—through it. There’s real value in that individuality, and it’s worth embracing the unique way you interpret the world. Once you learn what questions to ask, that is, how to see, drawing becomes a natural extension of thought.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.