Hot Take

Photo by Conleigh Bauer

Photo by Conleigh Bauer

Being a sustainability leader in Texas is not for the faint of heart. Over the years, I have grown thick skin and gotten good at talking about the benefits of sustainability without using that particular word, which can be politically loaded. Instead, the conversations became more about saving money, increasing energy independence, or creating healthier indoor environments. Those roads often lead to the same place, just with fewer potholes.

Something else that is not for the faint of heart: owning a 102-year-old house in an increasingly extreme Dallas climate. Like many older homes in Texas, ours has a pier-and-beam foundation, zero wall insulation, and its original single-pane windows—52 of them to be exact. It is drafty and cold in the winter and struggles to stay cool in the summer. But as an architect with an affinity for old houses, I was drawn to its deep overhangs, generous front porch, and undeniable charm.

Then came Winter Storm Uri in February 2021. We were among the millions of Texans who lost power for days. Our charming home quickly fell to below freezing inside, and we had to seek refuge elsewhere. The storm caused no lasting damage, but it did trigger a series of financial and environmental wake-up calls.

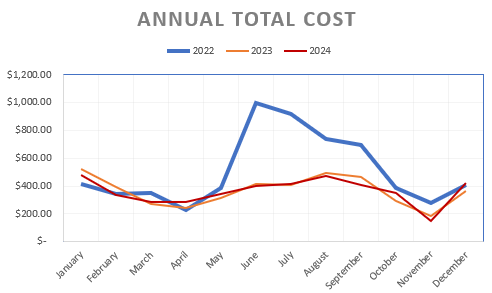

Uri made international headlines as the self-proclaimed “Energy Capital” of the world watched its grid falter and its residents left freezing in their own homes. How the storm drastically increased electricity and natural gas prices was not as newsworthy. Our electricity rate jumped from 0.09/kWh to 0.19/kWh. Suddenly, our bills skyrocketed from a few hundred to nearly a thousand dollars a month—an expense impossible to ignore.

And so began my heat pump journey.

As an architect who specializes in sustainable design and construction, I would like to think I have a thorough understanding of how to make my own home more energy efficient. When we purchased the house, it came with storm windows that increased thermal resistance, a tankless hot water heater, and an induction stovetop, so we had a head start. We later added attic insulation and weather stripping but found wall insulation and window replacement to be too invasive and costly. We knew that the HVAC units were old, so we were not surprised when the upstairs system failed in the spring of 2023. I knew immediately I wanted to evaluate heat pump technology before getting locked into more fossil fuel combustion for at least another decade.

Let me pause here: the term “heat pump” is in dire need of rebranding. Unlike a traditional boiler or furnace, a heat pump does not actually generate heat but simply moves it around. In the summer, it functions like a traditional air conditioner, removing heat from inside the house and expelling it to the outside. In the winter it simply works in reverse, pulling latent heat from the outdoors and transferring it inside. This makes it highly efficient. Variable speeds further boost its performance, increase thermal comfort, and reduce noise. Plus, heat pumps eliminate the need for natural gas combustion, improving air quality and cutting carbon emissions. If all of this greatness is not enough, heat pumps are eligible for a federal tax rebate up to $2,000 thanks to the Inflation Reduction Act.

But do they work in subfreezing temperatures like Uri? You will find conflicting views on this, but I concluded that older models did suffer from inefficiency, sometimes extreme, when temperatures dropped well below freezing. This certainly gave me pause, considering that at least one annual extreme winter event seemed to be increasingly likely. However, the newer generation of heat pumps, assuming they are sized correctly and come from reputable dealers, are much less prone to this inefficiency, even in subzero temperatures. This point was driven home for me when visiting Maine around the same time I was HVAC shopping. I saw houses with heat pumps everywhere, presumably due to the high cost of heating oil. There were heat pump retailers in virtually every strip mall. Surely, if heat pumps were a viable technology in a cold climate like Maine, they could handle the occasional Texas winter storm. I returned home determined to buy one.

It turns out, buying a heat pump in Dallas is harder than it should be.

I spoke with multiple contractors, and most of them tried to dissuade me. Their concerns—ranging from cost to winter reliability—were largely rooted in a lack of familiarity. Discouraged but not defeated, I finally found a contractor who had experience with the technology and agreed to evaluate my house.

He was not exactly a heat pump evangelist but noted their increasing popularity in higher-end new homes that benefited from eliminating natural gas piping altogether. He also acknowledged the hesitation among contractors: unfamiliar systems, fear of customer complaints, and a preference for the status quo. Because I already had the piping, he recommended a hybrid system—a primary heat pump with smaller natural gas backup—as peace of mind during rare cold snaps.

At this point, I was equally determined and hesitant. I admittedly only know enough about mechanical systems to be dangerous, so I worried that my own hubris was leading me down the wrong path. If this technology was so great, why was it so hard to find someone to sell me one? And we had not even discussed cost yet.

Not yet ready to commit, I asked for a range of proposals, starting with the cheapest and most basic traditional AC with a gas furnace all the way to the Cadillac of heat pumps, plus a few midpoint options between. To his credit, this contractor was up for the challenge and came back with four options: basic, better, best, and fantastic. The prices, across the board, were eye watering. Even the cheapest traditional system was roughly equal to four months of mortgage payments. Surprisingly, the “fantastic” option—the Cadillac of heat pumps—was not the most expensive. It actually came in cheaper than the mid-tier heat pump option, due to manufacturer and Oncor rebates.

In all, the traditional gas furnace systems were cheaper by 10-20% compared to the hybrid heat pumps. But when I factored in the $2,000 federal rebate, the cost gap narrowed to less than 6%, or around $1,000. That’s not nothing—but in the overall context of the cost, it was not everything either. Since I could not meaningfully predict the exact utility savings, I would have to take a leap of faith. I went with the Cadillac of heat pumps, which in this case was a Carrier Infinity variable speed heat pump with a natural gas backup. Like others on the market, it is designed to operate effectively down to minus 15 degrees Fahrenheit before its efficiency begins to decrease.

Two years in, did I make the right choice?

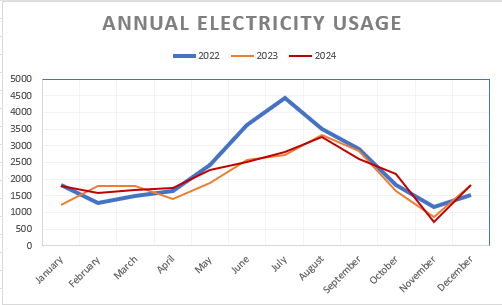

Unequivocally, yes. Let’s start with the dollars—the federal rebate came through with ease. If your tax burden is lower than the rebate amount, you will receive direct payment through the IRS. In reviewing our electricity and natural gas costs before and after we installed the heat pump, the summer savings were dramatic—we had reduced our energy usage consistently by more than 1,600 kwh per month and cut our bill in half. The winter savings were more modest, trading a lower gas bill for a slightly higher electric one. But the system’s efficiency kept the overall costs roughly equivalent.

By the end of the first summer, we had already recouped the heat pump’s cost premium. We are on track for full payback in eight years based on summer savings alone. Our ROI calculation assumes stable utility rates, which of course may change, but are unlikely to go down. If anything, the trend toward rising energy prices only strengthens the long-term case.

As for performance: it exceeded expectations. Even during two years of Dallas cold snaps, the system has maintained comfort without relying on the backup gas. We eventually overrode the gas altogether after finding the electric heat more consistent, more comfortable, and less jarring. Knowing what I know now, I would have skipped the natural gas backup entirely and gone with the fully electric option. Lesson learned.

Every house is unique, but firsthand stories like mine can help bridge the gap between manufacturer claims and lived experience. In my case, a heat pump proved to be an excellent investment—both environmentally and economically. If you are facing a system replacement, I strongly encourage you to consider one. Having navigated the ups and downs myself, here are a few words of wisdom that might make your path smoother:

- Experience matters: If your contractor has little or no experience with residential heat pumps, take their perspective with a healthy dose of caution. Often, it is not bad intentions but rather entrenched incentive structures and unfamiliarity that lead to outdated recommendations.

- Be manufacturer agnostic: You are better off finding a contractor you trust and working with their recommended product lines than falling in love with a specific system and struggling to find someone qualified to install it. Many reputable manufacturers exist, and contractors often receive better pricing from their preferred vendors.

- Talk in actual dollars: Do not assume that more efficient systems are automatically more expensive. Get real quotes and compare them.

- Understand the full cost picture: Most contractors will not include incentives like the IRA rebate in their proposals because they do not impact the upfront price you’ll pay them. But those rebates do matter. The Energy Efficiency Home Improvement Credit (Section 25C) was originally designed to be available through 2032, but the recent passing of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act significantly shortens that timeline of availability, phasing out the rebate for systems installed after December 31, 2025.

Retrofitting a century-old Dallas home with a modern heat pump was not just a test of technology—it was a test of patience, persistence, and perspective. In the end, the investment has paid off in lower bills, improved comfort, and the satisfaction of aligning our home’s performance with our values. But perhaps more importantly, it has shown me just how much inertia and misinformation still stand in the way of smarter, cleaner solutions—especially in markets like Texas where tradition and advancement are sometimes at odds.

Heat pumps are not perfect, and, as with all systems, they are not one-size-fits-all. But they are ready for prime time, even in the most unlikely of places. For architects, builders, and homeowners alike, the message is clear—the technology is here, the incentives are real, and the long-term benefits are tangible. The hardest part may simply be asking the right questions, challenging outdated assumptions, and advocating for progress—even when the industry says, “that’s not how we do things here.” As we brace for increasingly extreme weather events, the decisions we make about how we heat and cool our homes will matter more than ever. My advice? Don’t wait for the perfect solution. Choose the better one that is available now.