Throwing Shade

Texas has always had a reputation as a hot place. In the days before Willis Carrier brought the air-conditioning revolution, you didn’t venture inside the state from June to September without good cause, if you weren’t used to that big sky and fierce sun dominating your days.

Since that time, folks and industry have steadily migrated into Texas and other heat challenged states, seeking its open spaces and bold spirit. Mechanical cooling, however, masks the reality of intensifying heat and variable weather patterns that prolong periods of drought.

Growing up in Central Texas and Dallas-Fort Worth, I have often been struck by the relative lack of manmade shade. While the northern suburbs of the metroplex have increased the planting of shade trees and other vegetative cover, the built environment has negated most of that cooling effect with expansive development, roadways, and surface parking.

The adoption of mechanical cooling has significantly influenced the evolution of modern design, development, and construction. Floor plates have become much deeper since cross-ventilation was no longer required. This led to greater operational lighting loads and mechanical ventilation requirements. Operable windows in general have generally disappeared in large buildings as fresh air systems and climate control have replaced them. This became a problem during the response to the COVID-19 pandemic, when public buildings and institutions worried that infected air was not being moved at adequate rates.

As the modern movement became the de facto style of urban development in the middle of the 20th century, the sleek prismatic forms of the international style and corporate towers provided little shade or refuge, except for the imposing shadows of the skyscrapers themselves. Our cities have largely continued this trend, primarily due to the economic driver of leasable conditioned space.

European solutions

In Europe and much of the globe, the demand for air conditioning has been slower and less intensive for a long time. Exterior shutters, high-efficiency operable windows, and other modalities were the first line of defense to mitigate the energy expense of cooling loads. However, adoption still varies greatly by country.

We share hot dry summers with sunny Italy, which has long understood the beauty of relief and shade on a facade, as well as its practical purposes. Loggias were a godsend to citizens who walked out of doors frequently, while also lowering the ambient temperature near the building.

In desert climates, one passive strategy to fend off solar intensity is the double roof, or super-roof, where buildings are contained under a larger shade structure. Like the solar shutters common in Europe, a double roof stops the direct sun from heating up the building by deflecting it before it reaches the building envelope.

by SL Rasch GmbH

These types of passive approaches—deep overhangs/eaves, loggia, deep-set windows, cross-ventilation, and the like—have become less common in the modern air-conditioned environment, but they still play a role in reducing our dependence on energy intensive cooling.

Considerations

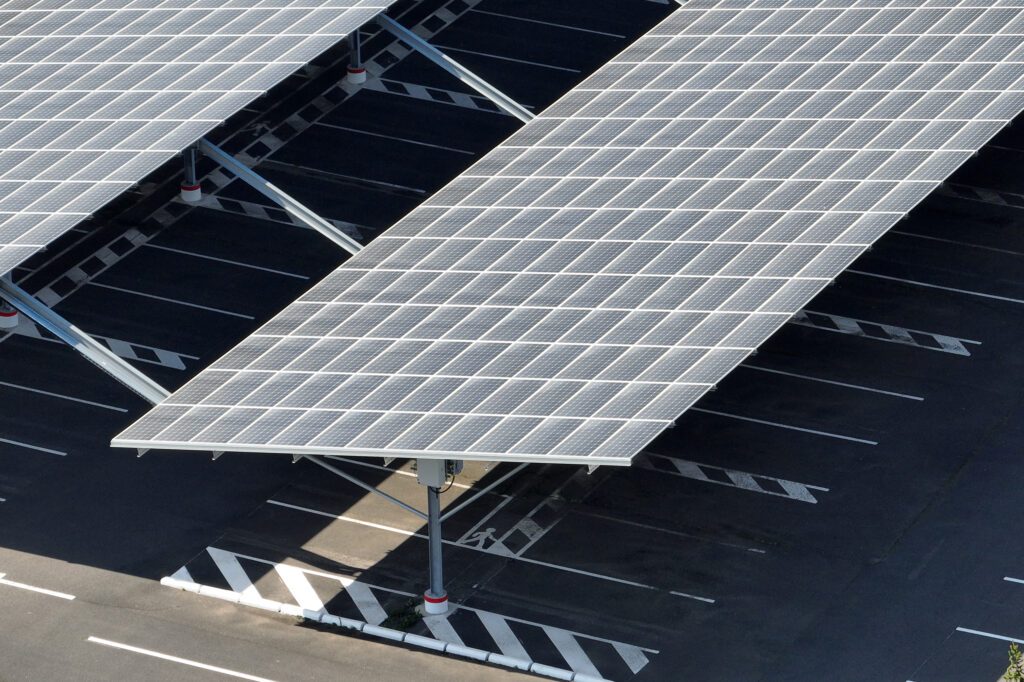

Shade is still the most fundamental passive solution to direct solar intensity, and commercial development is often lacking. I like to see shade canopies in office building parking lots protecting the cars during the day, often incorporating photovoltaics. This is not a cheap solution, but it has relatively low impact when compared to a multilevel concrete parking structure.

While it may be possible to plant trees—and in time they will help with heat islands—it will not offer enough relief on the hottest days. Many times, I have searched for a parking lot in July for the most direct path to the front door of a business.

Awnings and shaded walkways at the storefronts are not always a given either, but perimeter building shading creates a thermal buffer zone around the building envelope that mitigates direct sun. In 2023 alone, extreme heat added $295 to the average ERCOT customer bill—with $83 of that directly linked to climate change.

At the Venice Biennale this year, the USA Pavilion exhibited PORCH: An Architecture of Generosity. It provided a deep dive into porches/loggias/porticos as a cultural symbol, a climate strategy, and a principal form of human and civic engagement. The porch has been largely neglected in the last 40 years in home construction as homes have become more interior focused and less engaged with the block and neighborhood. The nominal porch has tried to make a comeback, but without a public life on the street fronts, it often is more of a signifier than an active part of the home.

The long porches and wrap-around verandas of Texas ranch houses have become scarce in the A/C era. However, the backyard has become the one opportunity for shade structures to make an appearance. There has been a resurgence of covered patios, trellises, and retrofitted shaded areas in contemporary single-family homes since these accommodate popular outdoor kitchens/living areas.

Looking to the future

I believe there’s an alternative built version of Texas that can be more regionally appropriate. I hope as designers that we would campaign for the spaces between buildings to be more hospitable. They are part of the city fabric just as much as lobbies and storefronts, if not more. These spaces need human scale amenities with water elements and shade implemented early in planning rather than ad hoc solutions as need arises. We should iterate on climate strategies that take the stress off building operational loads by creating shelter in its primary sense first and then creating the variety and degree of “climate control.”

A valuable resource for promoting design for change and resiliency can be found in the 10 principles outlined by the AIA Framework for Design Excellence.

As part of this cooler environment, low-slung buildings with overhangs and courtyards could create microclimates, water catchments could feed fountains, and resilient plantings could buffer verandas. Big box stores with blue or green roofs could be put to regenerative use as nurseries for plants. Housing with simpler roof lines could project again, giving us a sense of shelter and making it easier to collect rainwater for maintaining native and adapted gardens. While I don’t expect the towering, black-shingled hipped roofs of the suburbs to go away anytime soon, I do believe that we will start to see the sustainable wisdom of employing passive strategies to offset our increasing investment against heat.