At the Core of Regulation and Design

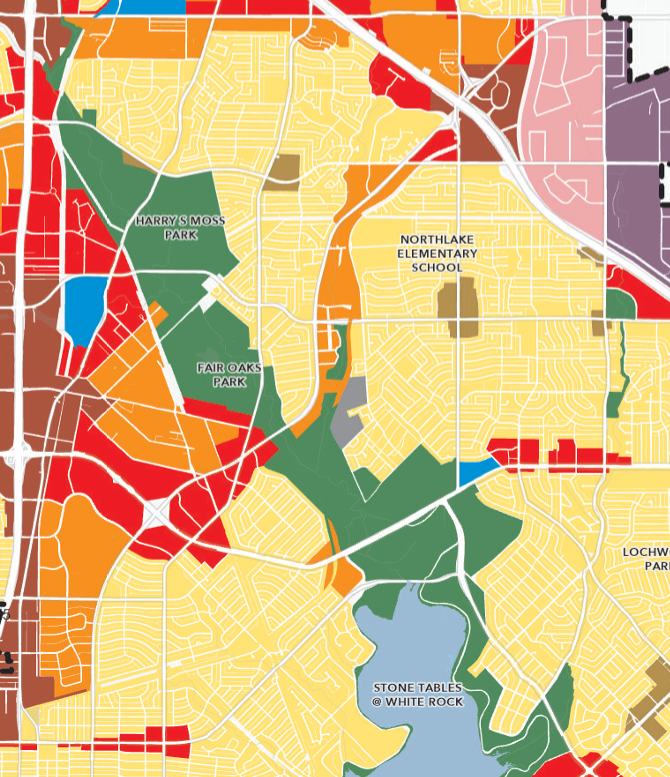

ForwardDallas Draft Placetype Map #7, 2024

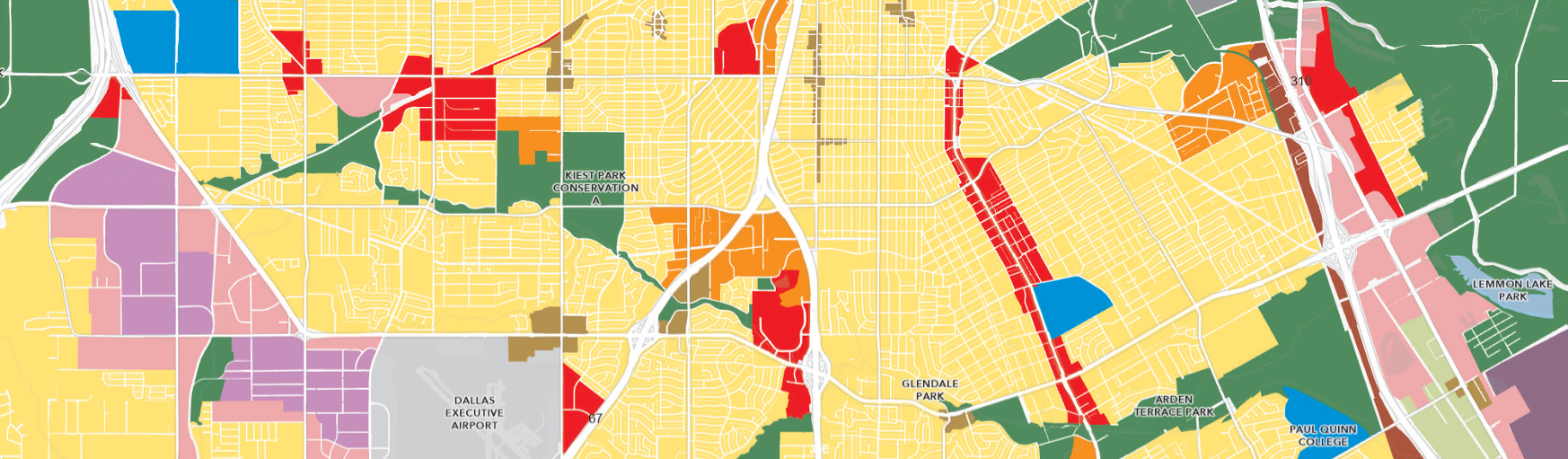

ForwardDallas Draft Placetype Map #7, 2024

Have you ever wondered what architects and lawyers have in common? If you think about it, the common language both professionals respond to is that of humans. Human needs, human interests, human behavior. People are at the core of design and regulation, and people are what we mutually respond to and focus on in our respective practices. They are the common “why.”

As we dig deeper, the following framework shows how architecture can be seen as a physical manifestation of the law, with a corresponding refresher on what legally constitutes real property and how that plays into our particular line of work. We then discuss how zoning practices can mitigate the competing relationship between public and private interests and further examine how we might balance a variety of legal constraints with the desires of owners and architects when designing infrastructure. Through this, we see how real property law interplays with the practice of architecture and how the human element is ultimately at the core of both disciplines.

To begin, we often view laws as something defining what people—and the entities they control—can and cannot do. Law, globally understood as a human artifact, constitutes an ensemble of regulations which have been enacted to categorize behavior into two categories: legal and illegal. Every individual subject to a law’s application is expected to have a working knowledge of its content to advise and hold accountable attitudes that are either respectful or hostile towards it. As applied to real property and design, the law is undeniably related to space as it requires a given territory with precise borders to be able to implement itself. Lawyers and architects alike who work in numerous municipalities, states, and even countries, must extensively research what rules are applicable in any specific locale at any given time.

Moving beyond the legal perspective, can we then see architecture as something tangible to help us express, represent, embrace and/or comply with these applicable laws, something that creates order out of chaos? Walls, fences, and gates can be understood as types of boundaries, as something that actually defines one’s legal rights to possess or access real property, while simultaneously excluding those that one wishes to keep out. Structures and buildings can even be territorial, asserting power or dominance or a generational lineage of land ownership.

Following this line of reasoning, architecture can be understood as a physical manifestation of law when you contend that the built environment does not merely reflect legal rules; it embodies them, enforces them, and often even anticipates them. Law becomes a feature of the environment rather than an annoying intangible constraint. Just as law structures human action through rights and rules, architecture structures such action through spatial utility and controlled constraints. Buildings and spaces give form to norms, regulate conduct, project authority, and shape collective life—often more powerfully and more quietly than written statutes. In short, architecture is law made visible. Law is architecture made explicit.

It bears repeating that “real property” is defined as land and anything permanently attached above or below it, including the surface of the land in addition to buildings and other improvements or fixtures (such as fences, driveways, and rooted landscaping) on the land that are deemed immovable.1 The terms of art referring to real property—known as the “bundle of sticks” or “bundle of rights”—include these tangible items as well as the related legal rights—surface, subsurface (such as mineral) and air rights, together with the rights to own, lease, control, improve, use, sell or otherwise dispose of the property—of course, within the bounds of applicable federal and local laws.

One concept my professor drilled into me as a young law student was that real property rights can be granted to another only to the extent you own them, and not a smidge more. For example, you cannot sell real property to a buyer if you do not own it through a prior legal transfer, such as via a signed and delivered deed. Similarly, you cannot grant an architect the right to perform tenant improvements in a building unless you are the owner or a third party with contractual rights to do so, such as a tenant or a property manager. This is why a full investigation of the subject property’s chain of title, leasing history, boundaries, permitted use, zoning, and related rights is always warranted during the due diligence period whether you are looking to buy, develop or lease. Some or all of that diligence should be performed by licensed professionals such as attorneys and architects.

How does this lesson apply to the human element? Well, the saying “real estate is king” has been noticeably popularized over the years, meaning that real estate (and the associated real property rights mentioned above) can frequently be seen as a highly valuable and even influential asset, especially as an investment strategy. In a free society where personal liberties are cherished, real property can be used to create wealth and prosperity, making possession of that so-called bundle of sticks the ultimate American dream. I would venture to say that, first and foremost, information is king. It can be powerful beyond belief. The more we have, the more equipped we will be. Maybe the secret to one relevant version of success is having the real estate and having a team that is well informed about the imposed guidelines on how one can and cannot take advantage of it.

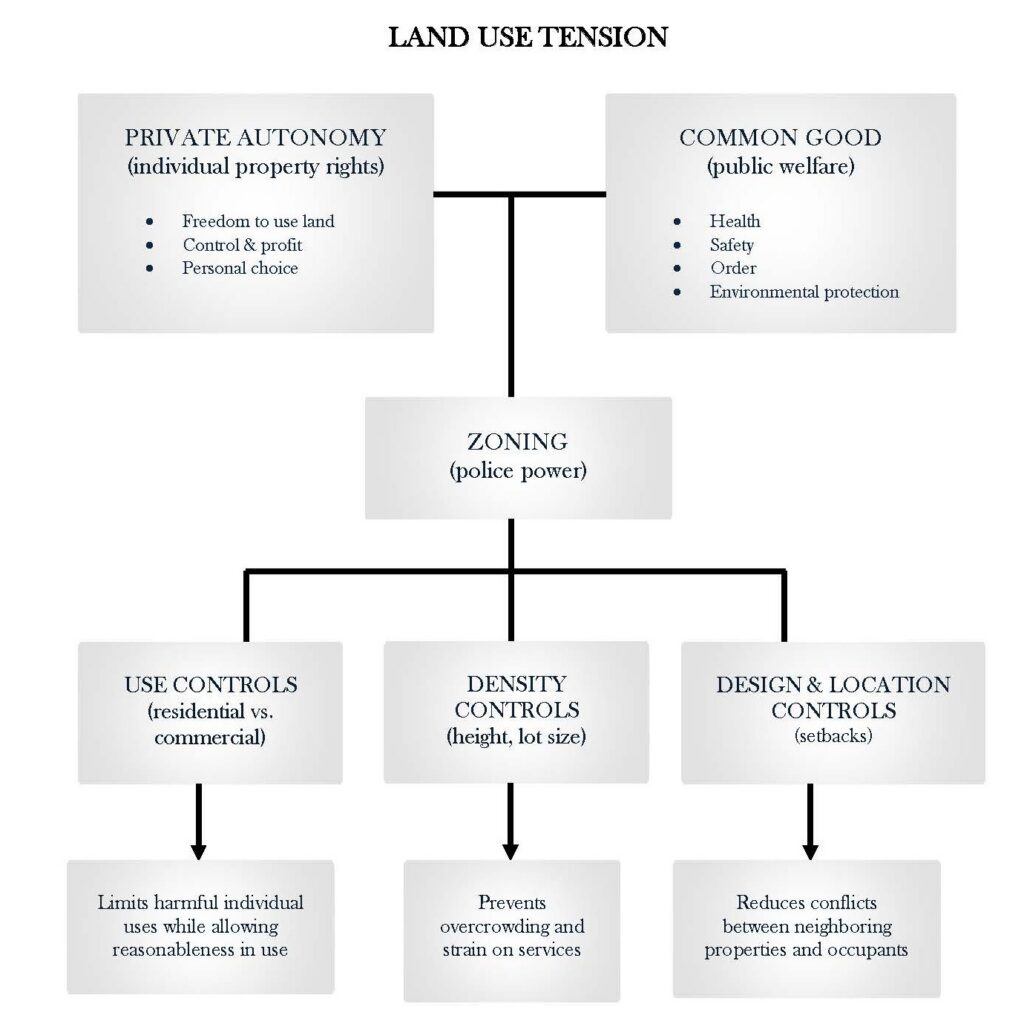

Now, on to zoning. If you’re anything like me, you might have sat in the coveted window seat on an airplane, gazed downward as you ascend to about 10,000 feet, and been struck by the structured continuity of the urban or rural landscape below—residential subdivisions, agricultural space, energy-efficient wind and solar farms, downtown skyscrapers or the like. This type of orderly community growth, made possible by comprehensive city land plans and development zoning regulations, is one of the benefits of having structured oversight and a tolerable number of regulations. Other benefits include protection of public welfare, health, and safety, safeguarding of private investment, allocation of land uses for collective efficiency, distribution of benefits and burdens, and the embodiment of community values in each built environment.

This is not to say that zoning eliminates the tension between private autonomy and the common good; rather, it creates a structured framework in which that tension can be managed. By shaping how land can be used, zoning becomes a legal as well as spatial tool through which society navigates what is best for individuals and what is best for the community at large. However, laws are synonymous with rules, and rules create power. This type of governmental power must be harnessed to allow for a level of human discretion as well as protection of individual choice, freedom, and self-realization by those holding legal rights to the land and structures. Allowing too much political interference in governing and overly restricting real property rights can be a declaration of power which is detrimental to a society.2 On the other hand, too much flexibility with little or no consistent regulation could create a zone reflecting the Wild West, where developers chaotically step on each other’s toes.3

Consequently, as citizens and professionals, we must take advantage of our rights to speak up at the local and state levels to harness the right balance between governing laws and the human “code.” Luckily, local zoning and other regulatory rules concerning real estate and development are typically built upon community input and lessons learned from past planning successes (and failures), while aligning with both city and state guidelines that regulate comprehensive plans. In a perfect world, zoning should function as a framework that balances the autonomy of individual landowners with public welfare and the collective needs of the community. This balance is never static; it reflects evolving social, economic, and environmental priorities.

ForwardDallas | Documents & Resources

On September 25, 2024, ForwardDallas was adopted by Dallas City Council.

The resources, reports, presentations, and analyses, are meant for you! They provide background on the city’s land use history, summarize community input to-date, and explore the possibilities for an equitable future.

Bringing these concepts full circle, and to assist both new and tenured architects and interior designers reading this article, the following outline intends to map out a handful of steps you and your design team can (and ought to) regularly implement at the early stages in the design process in order to find a satisfactory balance between the overarching rules and guidelines and the human and creative needs for a particular project. It is undoubtedly a central challenge in commercial real estate design. That said, the best projects are those that successfully reconcile regulatory requirements with identified financial and creative goals rather than treating law as a barrier.

- Begin with a regulatory baseline before design begins to prevent unrealistic expectations and avoid costly redesigns. To do this, assemble a clear map of all relevant regulations, including:

- Zoning (permitted and restricted uses, FAR, height, setbacks)

- Building codes (life safety, fire, egress, structural)

- Accessibility laws (ADA/local equivalents)

- Transportation requirements (parking minimums/maximums, loading berths)

- Environmental regulations (stormwater, energy codes, sustainability)

- Engage with the client to understand the owner’s goals in clear and measurable terms. Translating the following factors into explicit, quantifiable targets (e.g., “create a signature façade within energy envelope requirements” or “maximize leasable area within height limitations”) will create confidence in the design team:

- Financial expectations, budget, and underwriting models

- Adopted brand, image, and architectural identity

- Intended tenant mix and types of spaces, floor plate sizes, and amenities

- Anticipated timelines and speed to market

- Map out the intent and priorities of the architects to avoid conflicts with owner priorities and governing regulations. Oftentimes, the following items are prioritized:

- Aesthetics

- Spatial experience

- Innovation with materials and form

- Urban integration

- Environmental performance

- Creatively exploit legal constraints as design drivers instead of merely treating them as impediments. Think outside the box and use the rules as a design tool for innovation rather than a hindrance to creativity. For example:

- Height limits4 → Celebrate a stepped massing or rooftop amenity instead of fighting the cap

- Setbacks → Use terraces and outdoor spaces that add leasing value

- Energy codes → Drive façade innovation that becomes a branding element

- Parking requirements → Integrate shared-parking arrangements to reduce footprint

- Accessibility accommodations → Design an aesthetically pleasing ramp as part of the main entry point instead of slapping on a lackluster ramp at the back exit

- Engage in early dialogue with planning departments and code officials to reduce uncertainty and to expose strategic options. Treating regulators as partners instead of obstacles will allow you to achieve more flexibility with less conflict. A few benefits of engaging with authorities early and often include:

- Clarification of ambiguous zoning interpretations

- Revealing possible exceptions, variances, or density/incentive bonuses (as a trade-off for providing something of public value in the project)

- Building trust with the powers-that-be

- Shortening approval timelines

- Bring all stakeholders (e.g., owner, architect, engineer, contractor, attorney, landscape architect, anchor tenants, etc.) together to ensure all voices are heard, constraints considered, and friction reduced before committing to a final design direction.

- Create balance through a comprehensive paper trail by regularly documenting why decisions were made, what trade-offs were evaluated, how the design meets (or exceeds) legal obligations and how the ownership goals are satisfied. This will help to safeguard against future disputes.

In the best commercial projects, laws do not limit creativity. Instead, they are channeled into solutions that serve both public welfare and private ambition. This approach harmoniously melds individual human desires with social needs. A central purpose and a specified plan can make conflicts between the law, owner goals, and architectural vision easier to navigate along the way, with the goal of saving everyone both time and money.

While conforming to regulatory standards can certainly prove challenging at times, keeping the human element at the core of design and law is what allows real estate projects and industry professionals to continually grow and prosper. I encourage each of you to utilize the tools outlined above and never lose sight of our common “why.”

End Notes

- https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/26/1.856-10 ↩︎

- https://www.hillsdale.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/FMF-2008-Property-Rights-in-American-History.pdf (see Property Rights in American History written by James W. Ely Jr. of Vanderbilt University, which states in part: “Americans of the founding generation were not original in stressing the rights of property owners. Instead, their views were strongly shaped by the English constitutional tradition. Colonial Americans revered Magna Carta (1215) as a safeguard against arbitrary government. Several provisions of this famous document protected the rights of property owners: (1) The king agreed not take, imprison, or disseize a person of property ‘except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land’. The ‘law of the land’ clause was the forerunner of the due process norm. (2) The king promised not to take provisions without immediate payment. This language acknowledged the principle that government must pay the owner when it acquires private property. (3) The king further pledged that ‘[n]o scutage or aid shall be imposed on our kingdom unless by common consent of our kingdom.’ This language was the origin of the norm that government could not levy taxes without consulting a representative body. In time, these as well as other provisions of the Magna Carta would evolve into important principles of American constitutionalism.” ↩︎

- Take the city of Houston, for example. While the lack of traditional city-wide zoning may be welcomed as allowing for flexibility and diverse development (such as homes next to businesses), their alternative development regulation through other types of codes and ordinances and deed restrictions face criticism for lack of predictability (causing pains in future planning), perceived urban sprawl and allowing for undesirable land uses next to each other. Just search Google for “weirdest images to come from Houston’s lack of zoning laws” and you will get a flavor of what this approach looks like. ↩︎

- https://skyscraper.org/skyline/impact-of-1916-zoning/ (discussion of Hugh Ferriss and the 1920’s “Four Stages of the Maximum Mass of the Zoning Envelope” – this article states in summary that “[b]ecause developers sought to exploit every square foot of rentable space allowed, this template for the maximum mass or “envelope” a building could fill determined the characteristic stepped-pyramid shape of the city’s skyscrapers.”); https://nextcity.org/urbanist-news/new-york-1916-zoning-law-setback-architecture-design (further discussion of how the Manhattan skyline was shaped by zoning laws). ↩︎