Contested Ground

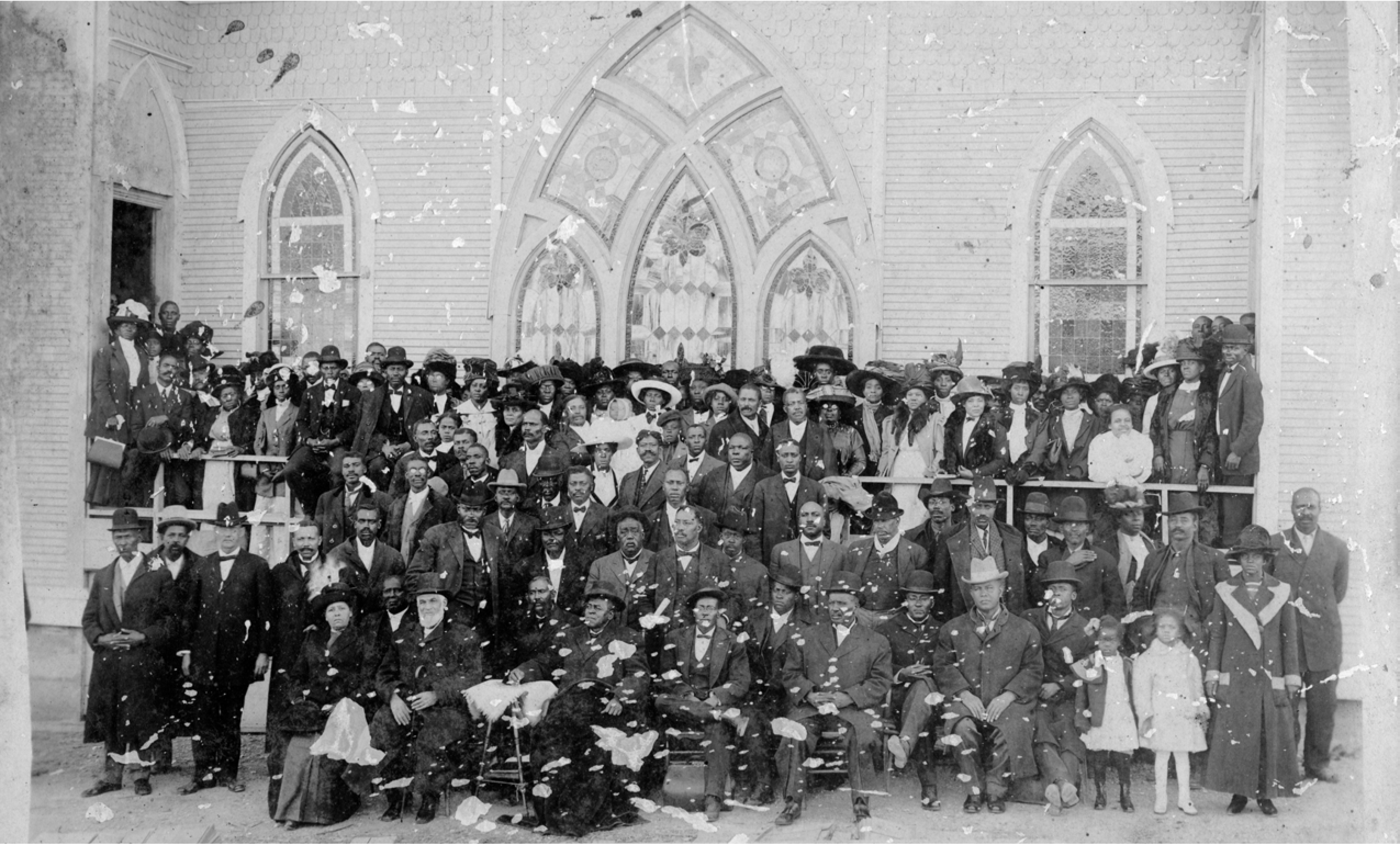

Elizabeth Chapel AME Church Congregation, 1911. Image courtesy of David Perry

Elizabeth Chapel AME Church Congregation, 1911. Image courtesy of David Perry

“Here” is contested ground.

In 1957, the proposed Interstate-35E started construction at the Cadiz Street Viaduct on the southern bend of the Trinity. It was a move toward “progress,” an integral part of the United States Interstate system that linked the expanding Oak Cliff to the booming post-war financial center of Downtown Dallas. Running parallel to Jefferson Avenue just north of the Dallas Zoo at Marsalis Avenue, construction required the use of eminent domain, forcing the sale of homes to provide land for a multi-lane freeway that continues to serve suburban developments. Construction tore through the neighborhood fabrics of east Oak Cliff, erasing 466 buildings,1 including 176 homes in the Tenth Street neighborhood, one of Dallas’ oldest neighborhoods with deep ties to the African American community and life in the city. Tenth Street was a part of the Oak Cliff Freedman’s Town, a self-established community built through familial ties, mutual aid, and black economic power despite Jim Crow segregation. Today it exists as the most intact historic Freedpeople’s town in the United States with descendants, residents, and professionals committed to its preservation and future growth. The history of Tenth Street is a story of self-determination and community empowerment that centers land, family, memory, and resistance.

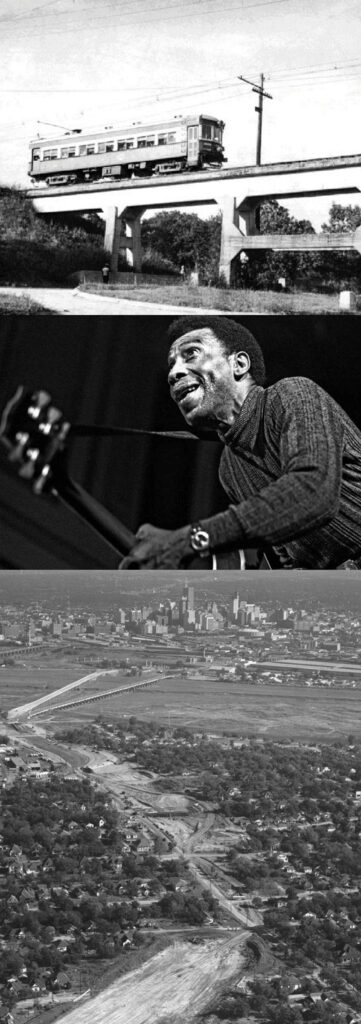

The Trinity Heights Streetcar. Part of the Interurban Railway System ran between

the Tenth Street District neighborhoods and Downtown Dallas. The bridge where it crossed over Clarendon Drive still stands today. Source, Dallas Morning News (top right)

T-Bone Walker, 1972. Tenth Street Resident and visionary blues musician T-Bone Walker was posthumously inducted into the both the Blues and Rock and Roll Hall Of Fame. Source, Wikimedia Commons (middle right)

I-35/South R.L. Thornton Highway Clearing. Image courtesy of UT Arlington Special Collections (bottom right)

Neighborhood and cultural erasure is no accident; it’s a hallmark of urban renewal and the prioritization of progress and capital at the expense of community and difference. While much of this expression of modernity has come and gone, contemporary urban policy, development, and construction practices continue to center capital at the expense of community. Urban erasure leaves communities to fend for themselves, stitching together memories from oral tradition, family photos, remaining landmarks, and historic archives. From the debris of state violence to the forces of gentrification, Tenth Street embodies this struggle and the fight between physical vulnerability and persistent memory. This neighborhood’s story shows that “here” is a set of relationships within a broader tapestry of mental images and physical urban artifacts, and that those relationships are dynamic states of being that can be torn asunder.

Simply put, unrepentant and uncritical demolition leads to a significant loss of cultural identity that’s inscribed in the urban form; culture is literally embedded in the brick and mortar of the storefront. But in 2025, living with the convenience of I-35E whipping us from DeSoto to Dallas, one might feel that the loss of historic homes was unfortunate but necessary in the pursuit of progress; the rest, as they say, is “history.”

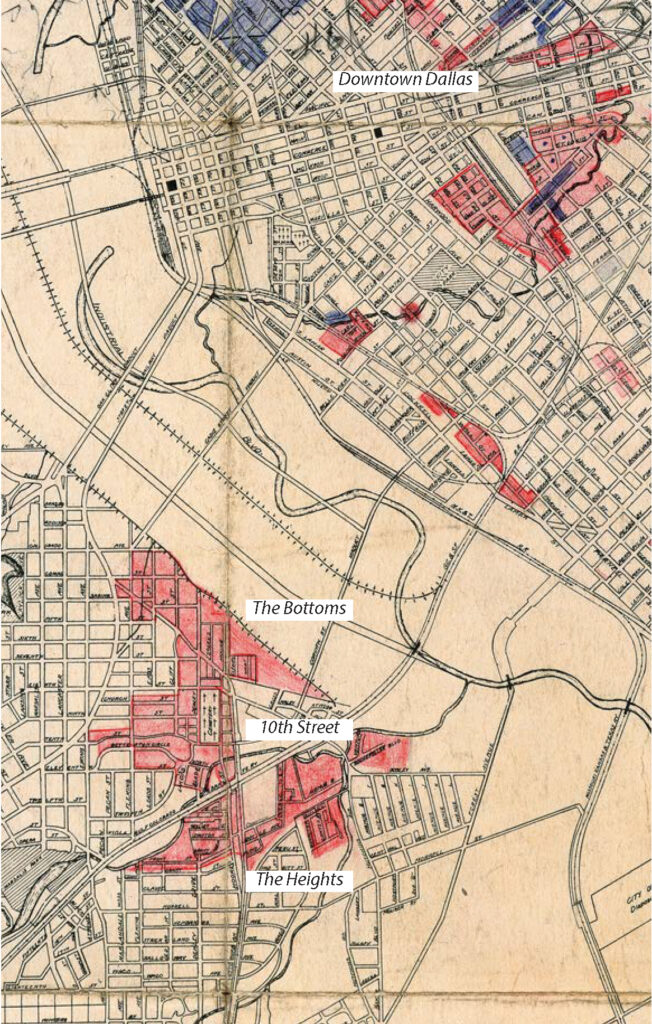

Oak Cliff Addition. Murphy & Bolanz compiled maps of Dallas dating between 1880-1920. The Oak Cliff Addition stretched from Miller Street to the east and Spring Lake (Lake Cliff) to the west. The Tenth Street neighborhood was a part of the larger mapped addition. Image courtesy of the Dallas Public Library

City of Dallas ‘Redlined’ Map. The Department of Public Works created a map identifying Black and Mexican sections within Dallas. This map reflects the same intent as those created by the Federal Home Loan Bank and Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC). Created in 1933, maps such as the above were created as a housing appraisal system to categorize the riskiness of lending to households in different neighborhoods. These color-coded maps are often cited as the originator of mortgage ‘redlining.’ Black neighborhoods were marked as red or “hazardous”. Source, City of Dallas Archive, Department of Public Works Map

Contested History, Artifacts, and Memory

It was along the southern banks of the Trinity River in 1888 that two Freedpeople from Alabama—Anthony and Hillary Andrew Boswell—purchased land and established homesteads in the subdivision of “Miller’s 4 Acres” on the outskirts of the whites-only town of Oak Cliff.2 Amidst strong bur oaks, mature American elms, riparian sycamore, and native prairie, Black families may have lived and worked in the area as early as 1865; however, documented land ownership begins with Freedman Anthony and Hillary A. Boswell along the tributaries and springs of Cedar Creek.

Over the next 20 years, the community grew through chain migration and hard-earned economic investment by Freedpeople who bought and built homes through their own labor, building what would become the Oak Cliff Freedman’s Town.3 During the early 1900s, the Tenth Street neighborhood grew into a vibrant community with over 1,000 residents,4 making it the heart of social, economic, and political activity.5 Further, the interconnectivity between the Oak Cliff Freedman’s Town and other Freedman’s towns such as Short North Dallas and Deep Ellum by the Trinity Heights Streetcar (part of the Texas Electric Interurban Railway System) shows that Black communities at this time were economically linked6 while also retaining distinct identities and autonomy. By the 1930s, the Oak Cliff Freedman’s Town was one of the largest in the city, second only to Short North Dallas in both population and land area.7

It was during the establishment of the neighborhood that three particular urban organizational anchors developed. Today, the Creek, the Cemetery and the Church continue to remain vitally important to the defining identity of “here”8 as physical and psychological anchors that hold a lived, emotional, and present-oriented social memory tied to a specific built environment.

As articulated by the mid-century architect Aldo Rossi, cities are repositories of collective memory,9 a phenomenon made possible through urban forms (homes, streets, businesses, cemeteries, churches) and geographic features (creeks, ridges, rivers). These artifacts act as vessels which transmit a shared identity across time and as fixed spatial organizers that become permanent and crystalize meaning, referred to as a “locus of identity.” According to Rossi, the locus is a set of relationships between a location and the buildings that are in it. It inhabits the material reality of the urban environment, the events unfolding around it, the thoughts of its creators, and the uniqueness of the site.10 Crucially, the locus of Tenth Street holds potent political and contested historical meaning. Tenth Street’s formation was a purposeful exercise in acquisition and autonomy, a tangible expression of Black landownership and self-determination in the Reconstruction era.

The Creek

Used by residents for drinking water and fishing, Cedar Creek and other local tributaries were necessary material resources that also held spiritual significance, as water is symbolically related to Christian rebirth through baptism.11 Carrying both material and symbolic power, the creek is deeply woven into the lived experience of the community as the originally developed land contained indigenous springs which fed into Cedar Creek. Creeks and their geological impressions have become both literal and mental connections throughout the Freedman’s town (and urban spaces in general—the Trinity River, Five Mile Creek, White Rock Creek), reinforcing its sense of locus. One of the creek’s tributaries, known locally as The Branch, was historically a community corridor where wooden foot bridges were built for crossings between neighborhoods. Despite fluctuating creek levels, The Branch also provided a site for baptisms and a source of year-round drinking water.12 Today, The Branch is a dry depression running through the Betterton Circle extension as it was capped during the construction of Clarendon Avenue in the 1950s. This included the demolition of 36 buildings and erasure of the original “Miller’s 4 Acres” homesteads.13

Although the tributaries and springs are silent from the subsequent capping and the construction of I-35, the creek as a place continues to play an important role in the identity of the district as hopeful residents look to re-establish The Branch as a community corridor and connector (it currently sits as a vacant, unused city right-of-way).

Composite Images of The Branch at Clarendon Avenue. Source, buildingcommunityWORKSHOP

The Cemetery

While less dynamic than the waters of life, Oak Cliff Cemetery stands as the physical boundary and anchor along the eastern edge of Tenth Street. A fixed typological artifact, the 10-acre cemetery is a physical manifestation of the community’s connection to roots, kinship, memory, and identity. Founding families and community leaders such as Anthony and Hillary A. Boswell (likely cousins and founding members of Oak Cliff Freedman’s Town), Noah Penn (founder of Greater El Bethel and treasurer of the Brotherhood of Black Building Mechanics), and ancestors of the Cox family (who are both descendants and residents of the Tenth Street community) can be found in Dallas’ oldest cemetery, which dates back to at least 1846.14

The cultural significance of the cemetery as a physical anchor is a tangible link to the history of Tenth Street and a living memory for its descendants as the community lives with a daily connection to their ancestral roots. Furthermore, through ongoing dedication, residents, descendants, genealogists, and historians continue to uncover ancestral names from previously unmarked graves in the segregated African American section of the cemetery.15 The cemetery holds inherent memory of kinship and community. This deep ancestral connection speaks to the power of place held in this historical and physical space.

“…those buried here [at the cemetery] made it possible for future generations. How many areas in Dallas are still intact in this way?” – Shaun Montgomery, Tenth Street Residents Association

Tombstone of Anthony Boswell, who, in 1888 along with Hilliary A Boswell was the first to purchase lots in Miller’s 4 Acres; both are buried in Oak Cliff Cemetery. Photo Credit: SMU photo by Guy Rogers III

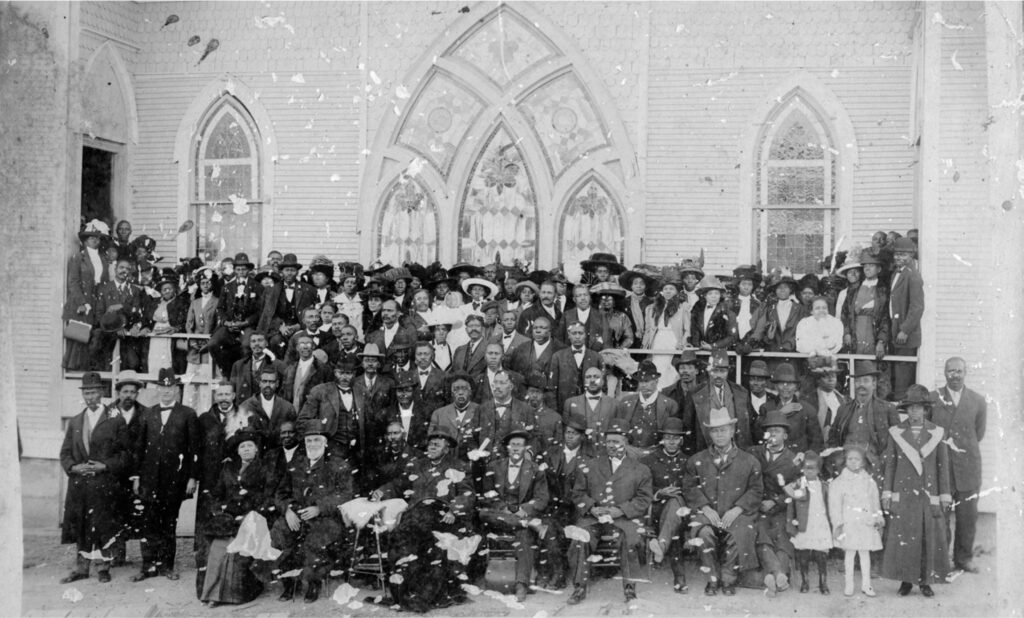

Elizabeth Chapel AME Church Congregation, 1911. Image courtesy of David Perry

The Church

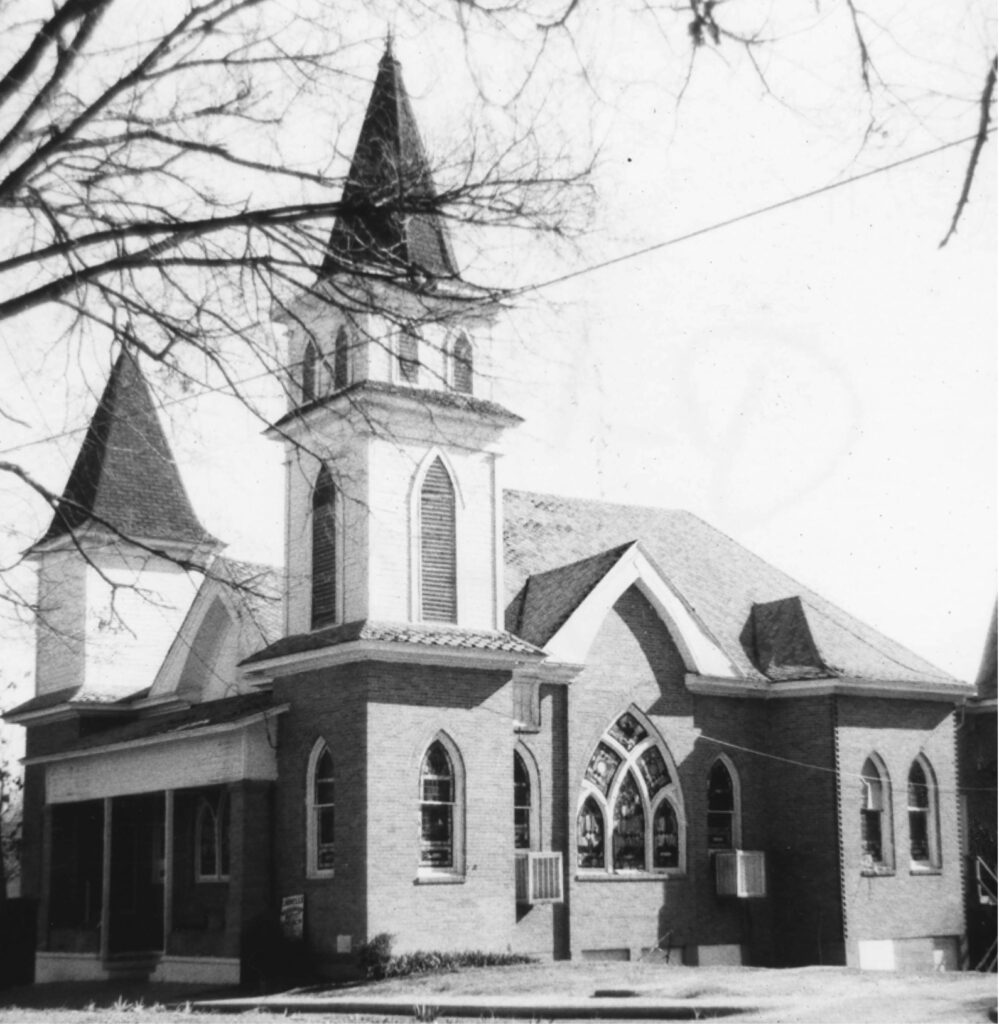

The physical anchor created by the cemetery is echoed by the communal and spiritual anchors generated by the neighborhood’s major social institutions. Churches embody a direct connection not only to the divine but to the community and family. Churches nurture social and civic life in a way that “kindle[s] the fires of brotherly and sisterly love.”16 At the height of its development, Tenth Street was home to more than 12 churches, each acting as its own nodal anchor where congregations provided mutual aid services, economic cooperation, civic engagement, and childhood education.17 The two most prominent churches, Greater El Bethel Missionary Baptist Church and Sunshine Elizabeth Chapel CME (Christian Methodist Episcopal) Church, established congregations in the late 1800s and built prominent churches that stood as major civic anchors throughout the nineteenth century.

Still standing today, Greater El Bethel Missionary Baptist Church remains deeply rooted in the lives of residents and congregation members. The church is a testament to resiliency within the community and continues to hold vital legacy. Recent historical speculation suggests that the sanctuary was designed by William Sidney Pittman, the first black architect in Texas and son-in-law of Booker T. Washington.18 Sunshine Elizabeth Chapel CME Church, whose namesake was Elizabeth Boswell, the wife of Anthony Boswell, was known for its tall twin spires. The church was a vessel of urban identity and community empowerment. However, after a failed effort to restore the building in the 1980s, it was demolished in 1996 even after the Landmark Commission’s nomination to rezone Tenth Street as a historic district.19 “It was hard to visualize the beautiful edifice deteriorate and not be saved especially since it was one of the oldest churches in the neighborhood and one of the first to receive a historical marker,” says Shaun Montgomery, TSRA. Both the congregation and the physical structures tell the story of thriving, interconnected communities with powerful spatial autonomy; this is where locus becomes place.

Sunshine Elizabeth Chapel CME Church. Built in 1911, the Sunshine Elizabeth Chapel AME Church was one of the two original church congregations in Tenth Street and an anchor in the community. The congregation moved in 1970, and the building languished, slowly deteriorating until it was torn down in 1996. While congregation members tried to save the historic structure beginning in the late 1980s, they were never able to raise enough funds to do so. Images courtesy of Preservation Dallas (left)

Greater El Bethel Missionary Baptist. The only remaining of twelve churches in the neighborhood sits at the corner of Cliff and Ninth Street, still used since construction completed in 1926. Photo Credit: SMU photos by Guy Rogers III (above)

A Place-Based Praxis

The infrastructural violence of I-35 led to an astounding loss of 43% of homes by 197020 and that number continued to grow through the 1990s after the district was granted historic designation in 1993. The strict preservation requirements (and therefore the high cost) for renovation and new construction led to further vacancy and out-migration during this period. In 2010, a city ordinance “that allowed homes in Landmark Districts to be torn down if they were smaller than 3,000 square feet” meant that nearly every home in Tenth Street could be demolished; this ordinance was not repealed until 2024.21 Today, the creek is capped and iconic structures razed. Many loci have disintegrated. While these facts are true, it is important to see this in contrast with the active reterritorialization and identity crafting that has continued since the neighborhood’s founding; in the midst of the catastrophes brought about by modernity and the erasure of black spatial autonomy, Tenth Street is still here.

In The Aesthetic of Equity, Craig Wilkins argues that traditional architecture and planning are dominated by a space-oriented approach. This approach is abstract, neutral, universalizing, and erases the cultural specificities of marginalized communities, a key feature of modernity. Instead, Wilkins proposes a place-oriented approach that centers on the lived experiences, memories, and differences of those communities. The demolition of Tenth Street was not just physical destruction but the imposition of a modernist, capitalist space (the highway as a conduit for traffic flow) onto a deeply meaningful Black place. This neighborhood is more than a locus precisely because it is a place, in Wilkins’ terms, of Black cultural production and resistance. Its fragmentation was the victory of abstract, bureaucratic space over embodied, communal place.

Early 1930s Composite Map of the Tenth Street Community. Prior to the Trinity River levee construction, there are approximately 1,700 residents according to the 1930s Census, growing to 2,200 by the 1950s. Composite Image, buildingcommunityWORKSHOP (left)

Present Day Composite Map of the Tenth Street Community. Together, the maps show the infrastructural violence and loss of ownership over the past 100 years. The construction of I-35 in 1959, Clarendon Ave, restrictive loans and covenants and the 2011 Demolition Ordinance led to only 191 lots occupied in the historic boundary; approximately 55% occupancy. Composite Image, buildingcommunityWORKSHOP (right)

Little Blue House Ribbon Cutting. TSRA members including Shaun Montgomery and Larry Johnson on the opening day of the Neighborhood Resource Center. The Little Blue House, recipient of the 2025 Dallas AIA Merit Award, is a testament to the ongoing persistence of cultural recapture, joy and spatial autonomy that exemplifies community participation and place-based design. Source, buildingcommunityWORKSHOP (top left)

Texas A&M Student Exhibition. Undergraduate students display their work that looked at preservation and vernacular architectural typologies in conjunction with the TSRA. Source, buildingcommunityWORKSHOP (middle left)

Blues in the Bottoms. Although not in the Bottoms neighborhood, this event celebrates the cultural heritage of the district throughout the 20th Century, Source, buildingcommunityWORKSHOP (bottom left)

In contrast, a place-based praxis requires true equity in the built environment, recognizing difference not as a deficit to be solved but as a cultural asset to be celebrated. Reactivation of urban space through adaptive reuse is a powerful tool for transforming alienating space back into lived place through community desire to reassert difference. Repurposing a shotgun house into a community center is an act of reterritorialization that simultaneously creates a locus and place that proudly declares its Black cultural identity against the homogenizing forces of development. Resident-led acts of cultural resistance within the neighborhood have been ongoing since the completion of the freeway; acts such as the preservation of urban anchors, public art exhibitions, storytelling performances, Juneteenth celebrations, and academic showcases all reflect a shared investment in creative expression, education, and neighborhood pride.

This activity embeds memory into newly imagined spaces, forging fresh collective narratives while preserving traces of the past, all while ongoing archival work insists on the reclaiming of spatial agency. Memories are reappropriated from contested spaces and narratives to create new chapters of cultural resilience that persist in a complex layering of place, even as the threat of gentrification looms both inside and outside the neighborhood. As gaps in housing, urban development, and public policy cannot guarantee community stability, there needs to be a confrontation with what we value, and what we will allow in the name of “progress.”

This, always, needs to be centered within a place-based praxis, lest we fall into the flattening tendencies of universalizing space at the expense of community power, difference, Creek, Church, and Cemetery.

Acknowledgments

This effort is indebted to the current residents of Tenth Street and the organizations who fight with them to retain memory and build new stories. Thank you, Ms. Shaun Montgomery and Mr. Larry Johnson for your stories. Thank you to Tameshia Rudd-Ridge and Jourdan Brunson at kinkofa for your generous time and insight and to the years of research and documentation work on Tenth Street through Remembering Black Dallas led by kinkofa in collaboration with Dr. Kathryn A. Cross and Dolores Rodgers. Gratitude to Robert Swann for identifying the connection between the Creek, Church, and Cemetery framework and its adaptation to the Tenth Street Historic District. And thanks to the ongoing community work of the Tenth Street Residential Association; despite what has come to pass and what will be, your story and your community are still here.

Footnotes

- Cross, Katie, “Tracing the Past, Envisioning a Future: Mapping Neighborhood Transitions in Tenth Street, Dallas, Texas” (Southern Methodist University, Department of Anthropology, 2024) ↩︎

- There is a popular narrative that’s been long misrepresented regarding the origins of Tenth Street, centering the myth of a benevolent enslaver rather than the self-determination of free African-Americans. Thanks to the archival work of kinkofa, no connection has been found between Judge William H. Hord and the founding of the Oak Cliff Cemetery. ↩︎

- kinkofa and Remembering Black Dallas, “The Origins of Tenth Street Historic Freedman’s Town District.” (2023) Board 6 ↩︎

- No historic evidence exists proving this is how the neighborhood referred to itself; it seems that the name Tenth Street District, referring to the primary street through the neighborhood, became the name of the district through the archival and historical analysis by Dr. Mamie L. McKnight in African American Families and Settlements of Dallas: On the Inside Looking Out. Exhibition, Family Memoirs, Personality Profiles and Community Essays, Volume II. (Black Dallas Remembered, Inc., 1990) ↩︎

- Cross, “Tracing the Past” ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- buildlingcommunityWORKSOP. Neighborhood Stories: Tenth Street (2013) 11 ↩︎

- Robert Swann was the first to identity the connection between the Creek, Church, and Cemetery framework and its adaptation from the Zion Hill Historic District to Tenth Street Historic District; McKnight, Mamie, Stan Solomillo, and Ron Emrich for ArchiTexas. Zion Hill Historic District: Preservation Strategy and Design Concepts. Submitted to the Nacogdoches Historic Landmark Preservation Committee (July 31, 1992) ↩︎

- Rossi, Aldo, “The Architecture of the City.” (MIT Press, 1984) 130 ↩︎

- Ibid. 103 ↩︎

- ArchiTexas/ Solamillo, “Tenth Street Historic District: A Historic African-American Neighborhood in Dallas, Texas, A Resident’s Guide to the History, House Types, Rehabilitation Recommendations and Preservation Incentives for the Tenth Street Neighborhood” (PDQ Press, Inc., 1994) 5 ↩︎

- Ibid, 6; buildlingcommunityWORKSOP. Neighborhood Stories: Tenth Street (2013) 8 ↩︎

- Cross, “Tracing the Past” ↩︎

- kinkofa and Remembering Black Dallas, “Sacred Ground: Preserving African American Heritage in Oak Cliff Cemetery” (2023) Board 2

↩︎ - Ibid., Board 1; Oak Cliff Cemetery Board. https://www.oakcliffcemetery.org/history/ ↩︎

- McKnight, M.L. “First African American Families of Dallas: Creative Survival. Exhibition, Family Memoirs, Personality Profiles and Community Essays, Volume I.” (Black Dallas Remembered, Inc., 1987) 34 ↩︎

- Cross, Katie. Tracing the Past… ↩︎

- kinkofa and Remembering Black Dallas, “Gettin’ Word: Religious and Spiritual Life in Oak Cliff Freedmen’s Town” (2023) Board 4 ↩︎

- National Register of Historic Places, Tenth Street Historic District, Dallas, Dallas County, Texas, National Register #94000604 (1994) ↩︎

- Cross, “Tracing the Past”; buildlingcommunityWORKSOP, “Neighborhood Stories.” ↩︎

- Erikson, Bethany. Mapping the Lost History of the Tenth Street Historic District. D Magazine, https://www.dmagazine.com/frontburner/2024/06/mapping-the-lost-history-of-the-tenth-street-historic-district/ (June 19, 2024) ↩︎