DFW

Courtesy of the Braniff Airways Foundation

Courtesy of the Braniff Airways Foundation

Most people going through the Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport today are more concerned about getting through security or making their connecting flight than noticing the design and architecture of the sprawling airport. In 1974, the new $700 million Dallas/Fort Worth Regional Airport, its original name, was the largest and most advanced airport in the world. The first to use computer-simulation analysis, the airport was a marvel of efficient planning and design. Its 66 gates spread across four terminals for nine airlines. It could accommodate the latest in aircraft, including the new Concorde and 747 jumbo jets. The massive airport eschewed typical airport design for an innovative layout with easily accessible gates and could accommodate future growth well into the new century without interrupting operations.

Early Air Travel in Dallas and Fort Worth

Passenger aviation took off in the 1920s, and by the 1940s, it had become more accessible to the masses. Both Dallas and Fort Worth had their own airports, with Love Field in Dallas and Meacham Field in Fort Worth.

In 1940, the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) proposed a joint airport for Dallas and Fort Worth. The cities began developing Midway Airport to serve both. However, Dallas backed out in 1943 after plans called for the terminal to be located on the west side of the field facing Fort Worth. Under the leadership of Amon Carter, Fort Worth continued the project in hopes that the CAB would designate the new Midway airport, which opened in Arlington in 1953, as the regional airport despite the lack of backing from Dallas. That did not happen. Both Fort Worth and Dallas continued to operate separate airports only 12 miles apart. Passenger traffic at Love Field continued to grow while traffic at Midway, also known as Amon G. Carter Field, never reached its potential.

In the early 1960s, Fort Worth unsuccessfully lobbied the CAB to designate the renamed Greater Southwest International Airport (GSIA) as the official regional airport. In 1964, CAB issued a statement saying it would not be in the public interest to designate GSIA or Love Field as a regional airport. After an appeal by both cities, the CAB gave an ultimatum. Both Dallas and Fort Worth had to decide on a site together, or the CAB would choose one. In an act of forced partnership, it set in motion what would become the largest airport development in the world.

Dallas and Fort Worth Build the World’s Biggest Airport

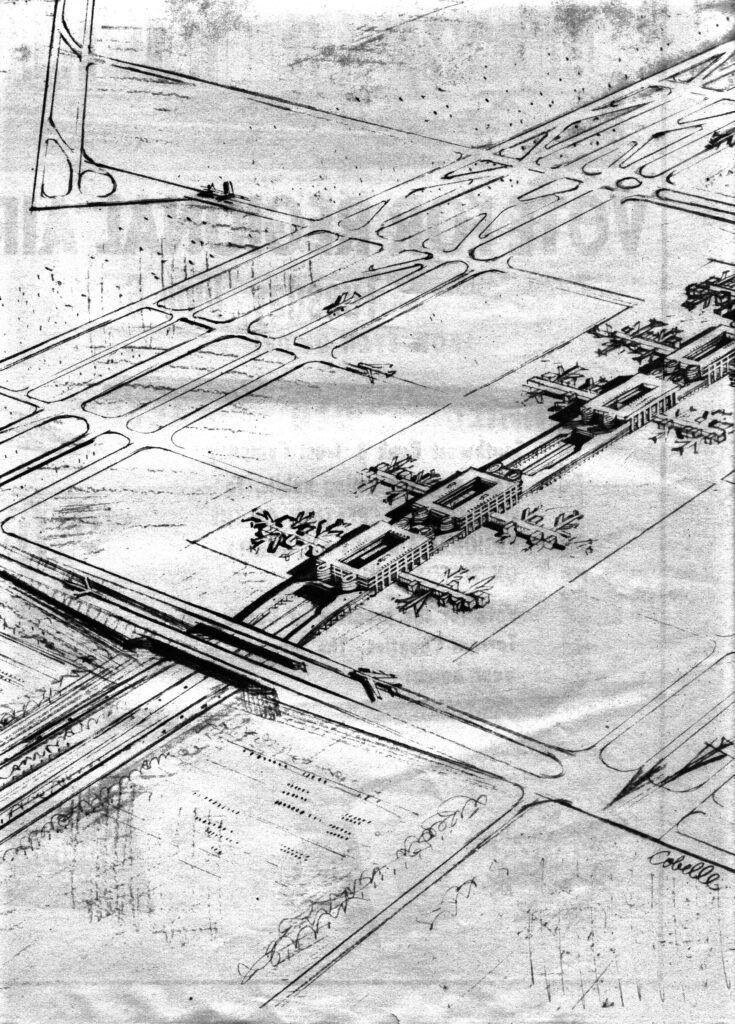

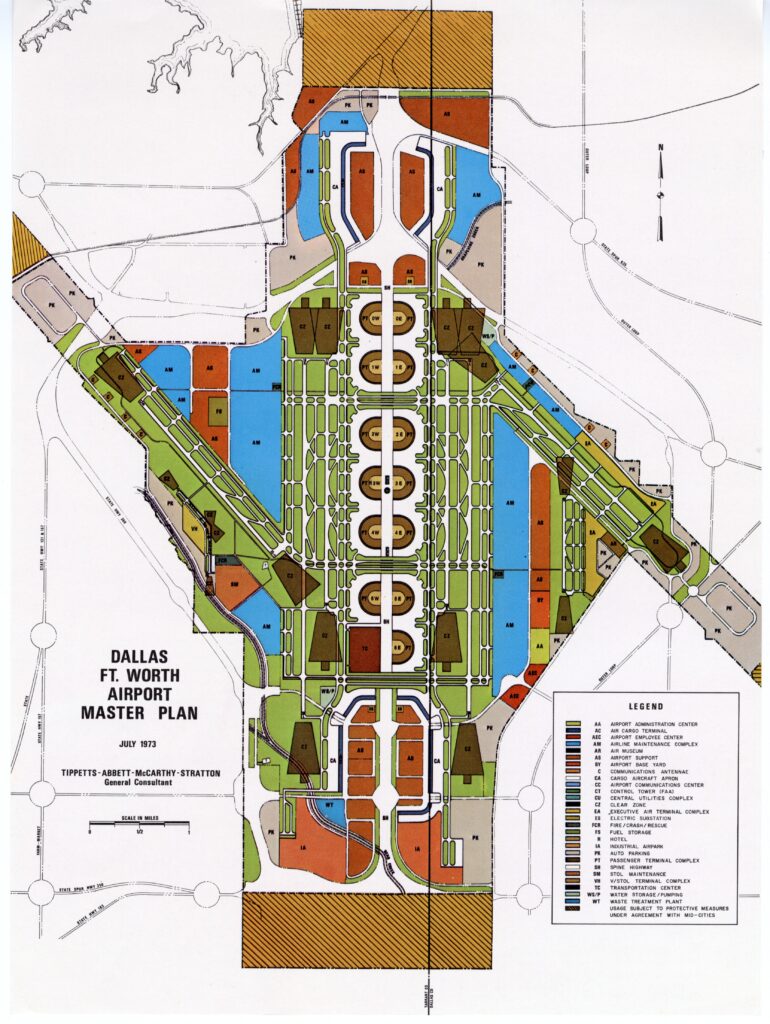

Dallas and Fort Worth selected representatives from each city to hammer out an agreement for the new airport. Erik Jonsson, the new mayor of Dallas, and Lee Johnson, the leader of the Fort Worth aviation board of the chamber, led the negotiations. The memorandum of understanding signed in 1965 started a new partnership which let to the quick hiring the engineering and architecture firm of Tippets-Abbett-McCarthy-Stratton (TAMS) from New York to begin site selection. They chose a site in September 1965 just north of GSIA and equidistant from Dallas and Fort Worth, straddling the Dallas and Tarrant County line. Their final recommendation called for acquiring 18,000 acres, which was ten times the size of GSIA. Love Field was only 1,300 acres.

With a site selected and the acquisition of land underway, architectural planning for the airport began. Traditional airport design of the time used a single terminal or head house structure to serve as the entrance to all the airport gates. TAMS rejected that idea and proposed a two-mile-long terminal accessed by an underground roadway, which allowed passengers to be dropped off at an entrance near their gates. Garages on top of each section of the terminal would provide parking. Jutting from the terminal would be finger-like extensions that could accommodate different-sized planes based on the airline.

Thomas Sullivan, the airport’s first executive director, was not fond of the design. He believed it was not forward-thinking enough for the new airport. He also believed the soon-to-arrive 747 jumbo jets would overwhelm the design if multiple planes arrived simultaneously, unloading hundreds of passengers each into the terminal.

Sullivan turned to Gyo Obata of Hellmuth, Obata, & Kassbaum in St. Louis, and Richard Adler of Brodsky, Hopf, and Adler in New York to create a new design concept. They only had eight weeks to get the new design approved by the airport board to stay on track for the planned completion date. TAMS’ role switched to serving as the construction manager for the massive project.

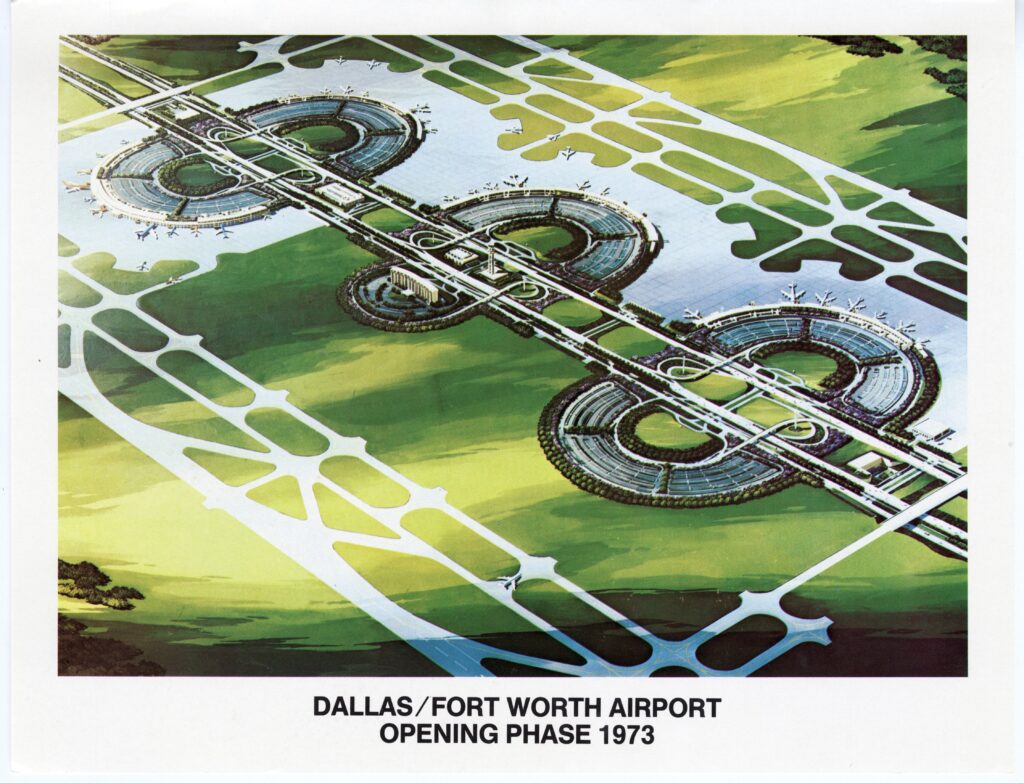

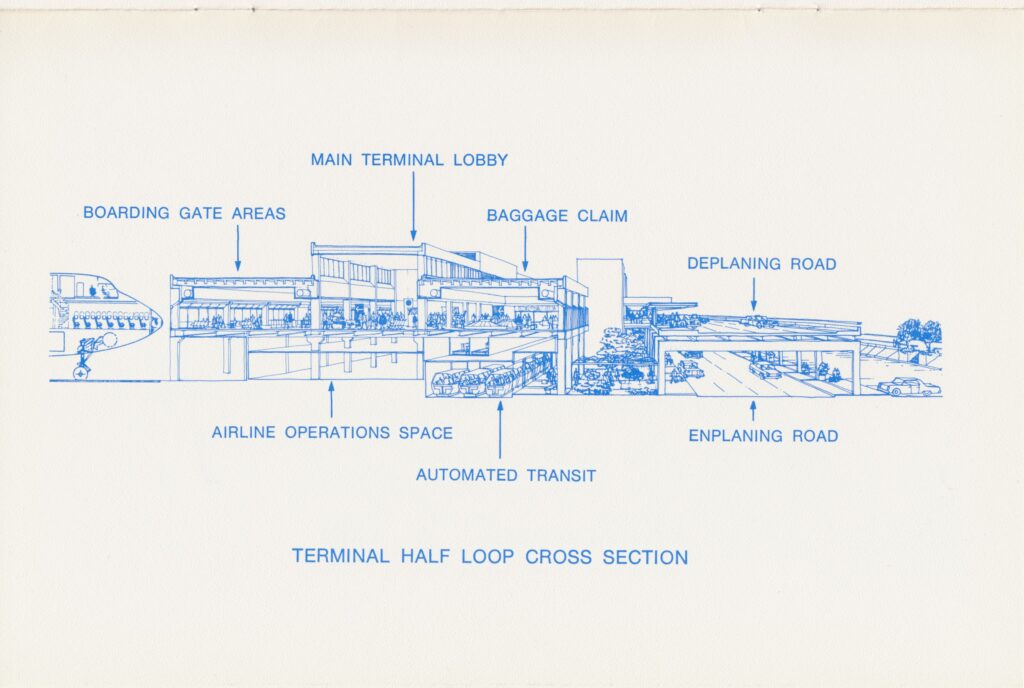

Obata served as project lead and developed a more radical idea of a decentralized design, which would be more human in scale than the TAMS proposal. He kept the spine but ditched the long single terminal for a series of smaller semi-circular terminals on either side of a highway. Each had a diameter of 1,800 feet and a circumference on the airfield side of 3,300 feet. The separate smaller terminals would make it easier to get from one’s car to the gate. Surface parking filled the inside area of each terminal, and with multiple entrances to the building, one could park close to the building and only walk between 300 to 800 feet to the gate. Comparable airports at the time required a walk of a mile or more to get from the terminal entrance to the gate area.

On the airfield side of the terminal, planes of various sizes could easily park along the curve of the building, including the new jumbo jets. Planes could also approach or back out from the gates without interfering with other aircraft.

Obata’s plan called for thirteen terminals to be built on either side of a ten-lane highway running north and south and intersecting with Highway 114 to the north and Highway 183 to the south. The initial phase of construction included four terminals—three on the east side, one on the west—three runways and supporting taxiways. The 11,400-foot parallel runways allowed for simultaneous landings to handle the high volume of flight traffic.

Groundbreaking took place on December 11, 1968, with a planned completion date of late 1972. After several delays and the completion of most of the facilities, a four-day dedication celebration took place in September 1973. It even included the first landing of the British Airways Concorde and the debut of the new 747 jumbo jet flown by Braniff International. Both aircraft were on display for touring during the opening.

Airlines waited to start passenger service until 1974 to ensure the airport was fully operational and would not interrupt the holiday travel season. On January 13, 1974, after five years of planning and four years of construction, American Airlines flight 341 from New York, with stops in Memphis and Little Rock, was the first commercial flight to land at DFW.

At the time the airport opened, advertising touted it as the nation’s largest and as big as Manhattan, New York. A map showing the airport boundary overlaid on Manhattan proved the point. The advertising also first used the term “metroplex” to describe the Dallas-Fort Worth metropolitan area. The ad defined the “Southwest Metroplex” as a complex of metropolitan areas and a planned 11-county economic region that encompassed over 8,360 square miles. They called it “…a megalopolis with leg room.” The new airport was also three times the size of New York’s Kennedy Airport, twice as big as Chicago O’Hare, and six times as big as Los Angeles.

Terminal Design and Construction

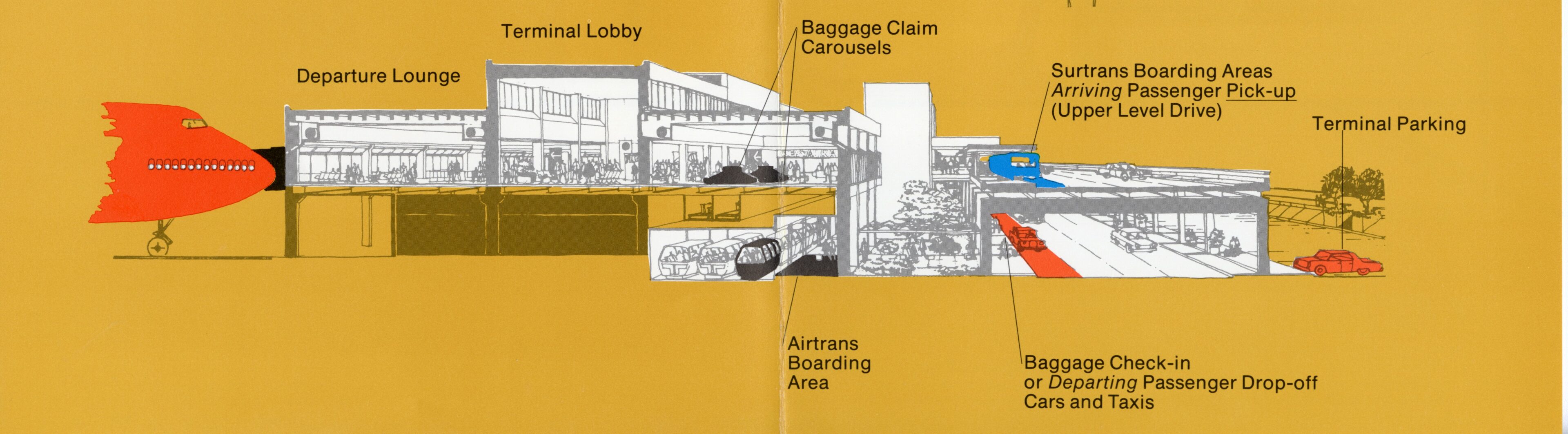

Obata designed the terminals to have the same layout for quickness of construction. Each terminal used a multi-level design and a two-level roadway that hugged the inside of the semi-circular design. The lower-level roadway was for departing passengers arriving either by car or by the automated people mover from other terminals. Escalators led to the main terminal level, which was 120 feet deep and divided into three rings. The innermost ring was 45 feet deep for baggage claim, the middle ring was 30 feet for the main lobby with ticket counter, shops, restaurants, and circulation, and the outermost ring of 45 feet was for the gate lounges. Below the main level was airline operations and baggage handling.

The upper-level roadway was used to pick up arriving passengers and was on the same level as the baggage claim. The design also allowed for an additional level if future planes required two levels of boarding.

There were no curved structural members used to make the curve of the building. The design used modules with structurally independent straight precast concrete members at 120 feet deep that included 90-foot-wide members on the airfield side and 80-foot-wide members on the land side. 12-foot-wide wedge-shaped sections placed at 93.5 feet on center created the curve.

The four terminals required over 18,000 individual pieces of pre-cast concrete. To speed up construction, the airport ordered the precast sections before the construction contracts were let. Texas Industries supplied over half the members and built a high-speed, ready-mix plant on the site to reduce delivery time. The original specifications called for sandblasted gray concrete with imported aggregate. However, Obata wanted a warmer color of concrete. Using local aggregate, Trinity Portland Cement in Dallas developed a unique warm-tone tan color more suited to Obata’s preference. Trinity’s color also came at a lower cost and allowed all buildings, parking structures, roadways, sidewalks, and entrance booths to have a consistent aesthetic throughout the airport.

Terminal Interiors

When the airport opened, the major tenants were Braniff International, American Airlines, and Delta Airlines. Minor tenants included Continental Airlines, Frontier Airlines, Eastern Airlines, Texas International Airlines, Ozark Air Lines, and Mexicana Airlines. Each airline designed the interiors for its portion of the terminals, working around the exposed concrete structural members and large expanses of bronze solar glass that bathed the interior in light.

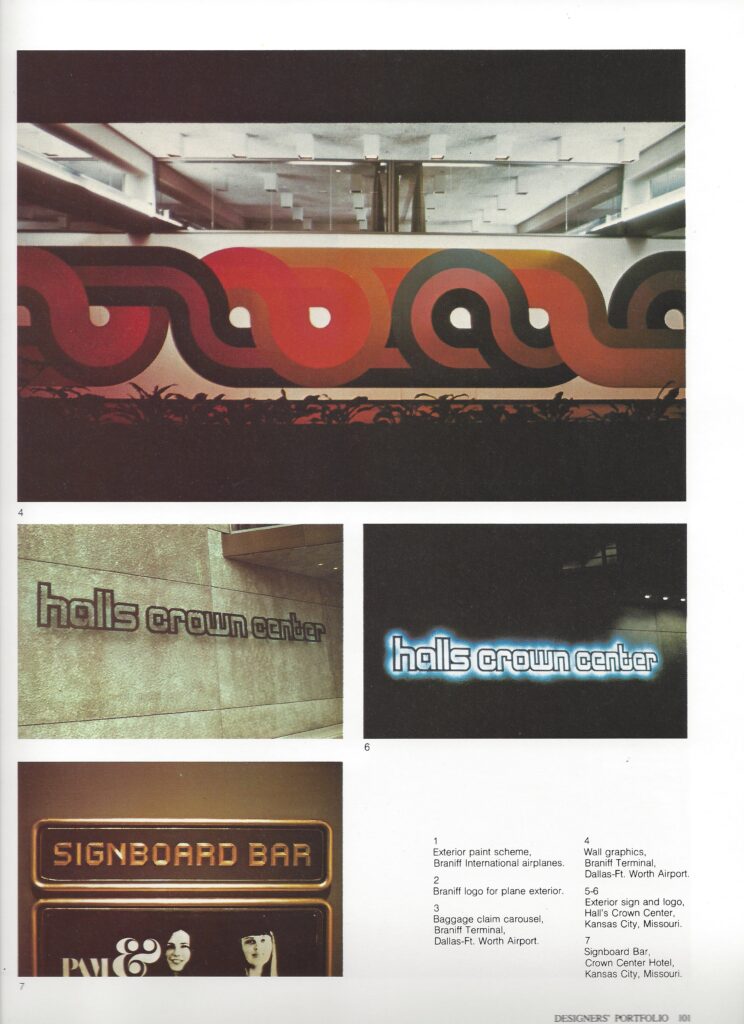

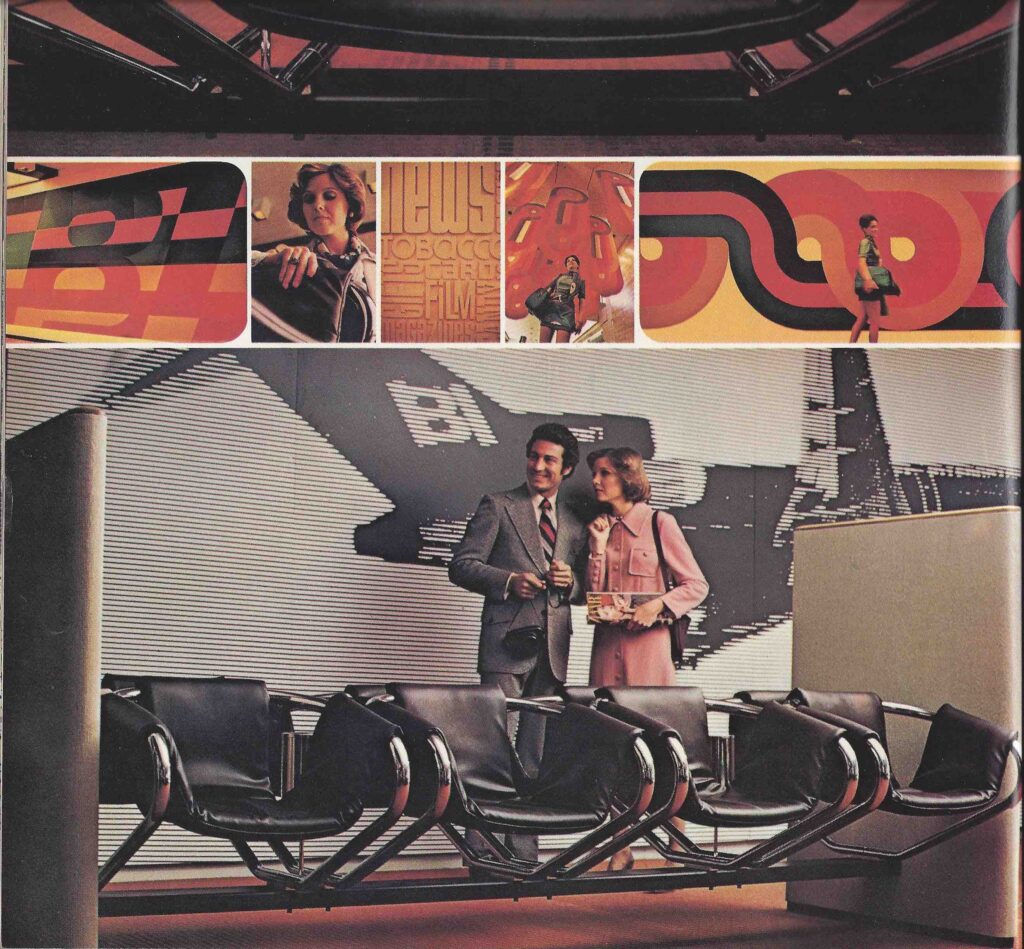

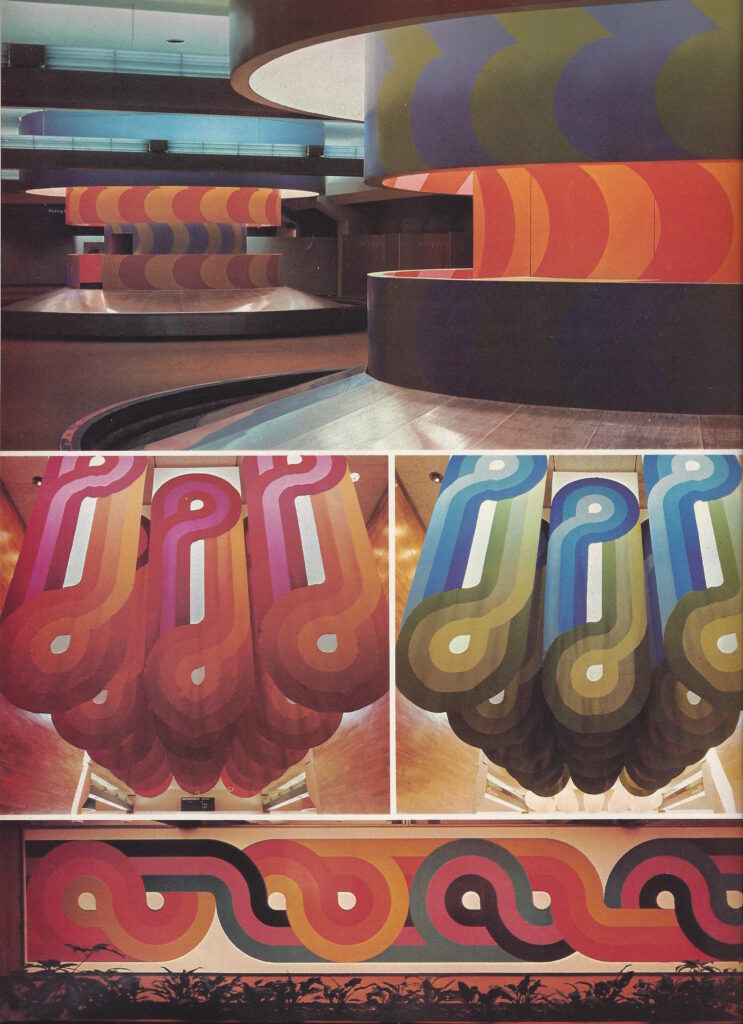

Braniff was the largest tenant at the airport and had its own dedicated terminal. It was also the most stylish with Braniff’s great emphasis on design. Their terminal showcased the latest style with Howard K. Smith and Partners designing the interior finish out while Harper + George handled the graphics and décor. Colorful terminal entrances featured brand-patterned wallpaper or brand bas-relief panels. Opaque dividers separated the eighteen departure lounges from the circulation corridor. Agent counters featured elegant black marble, chrome, tightly spaced large globe light fixtures above, and television screens with arrival and departure information. The gate lounge areas were warm and inviting with tobacco-hued Naugahyde sling seating divided by oatmeal-colored panels. The deep orange carpet contrasted with the warm-tone tan color of the exposed concrete columns and walls.

For American Airlines’ terminal design, Preston Geren & Associates of Fort Worth collaborated with American staff architects in New York. Edwards Field Carpet Makers created custom 10×14-foot panels that blended off-white tones with “deep sand” to mimic layers of a geological formation. The changing light from the clearstory would alter the colors throughout the day. Instead of individual gate lounges, American used one large lounge that could seat 500 passengers. Red carpeting covered the floor. The molded fiberglass seating had black and mustard-colored vinyl on chrome-framed bases. An Alexander Calder mobile from Love Field was moved to the new terminal.

Delta decided on a restrained but dramatic design by Neuhaus & Taylor with Robert D. White as the project architect. Rich blue and russet carpeting denoted the concourse and ticketing areas. Buff-colored vinyl covered the interior walls with blue vinyl on feature walls near the exits. Carpeted panels enclosed the gate lounges. Walnut-framed seating covered in Delta blue, black, and orange vinyl filled the space along with walnut tables. Buff-colored vinyl covered the curved counters designed to blend with the contours of the building.

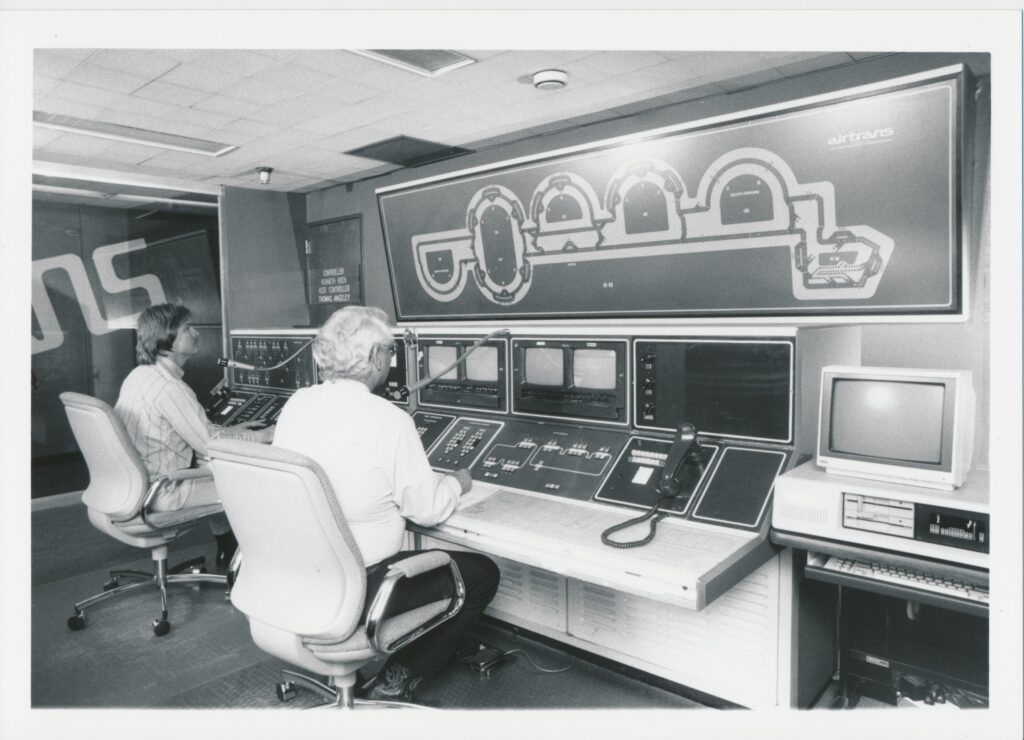

Airtrans People-Mover

To move passengers around the massive airport, a futuristic automated people-mover system called “Airtrans” was integrated into each terminal. Controlled by a central computer system, which used punch cards, it shuttled people between the four terminals and out to the north and south remote parking areas along a thirteen-mile route with a top speed of seventeen miles per hour. The $32 million system was the most sophisticated transit system in the world when it opened.

The individual cars, developed by LTV Aerospace of Grand Prairie, ran on rubber tires along a u-shaped concrete guideway propelled by electric motors. The guideway had a twelve-inch lime-treated subbase, two inches of asphalt, and eight inches of reinforced concrete for a smooth ride. Cars were twenty-one feet long, constructed of fiberglass over a frame, and could hold forty people. The New York firm of Walter Dorwin Teague Associates, known for its interior work on airplanes, designed the colorful carpeted interiors. Cars stopped at dedicated passenger stations at the lower level of each terminal, with an average wait time of ten minutes between cars.

Unfortunately, the Airtrans system was not the most reliable. The system was plagued with malfunctions, so buses often served as a backup to move passengers. The tires needed frequent changing in the summer to avoid melting when temperatures reached the high-90s. Car air conditioners broke down in the extreme heat. Winter ice on the rails caused electronic signals to malfunction and cars to stop on the route. The extremely complicated Airtrans system gave way to the much less complex and more reliable Skylink system in 2005.

Control Tower

In the middle of the spine highway rose the world’s tallest airport control tower at 196 feet. Designed by Welton Beckett and Associates, the innovative design used modular precast, post-tensioned hollow concrete units 10 feet square, 7.5 feet high, and 12 inches thick that weighed 20 tons each. Ninety-two stacked units created four shafts for stairs, elevator, power, and communications equipment. At the top was a 620-square-foot, 11-sided cab for air traffic controllers to view the complete airfield. At the base was a 25,000-square-foot building surrounding the tower for radar monitoring of flights.

DFW Airport Today

In 1985, officials renamed the airport “Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport” to emphasize its importance as an international hub for air travel. At the time, it was the sixth busiest in the world. Today, it is the third busiest after Atlanta and Dubai. Even with the growth, the airport has not reached its maximum capacity of thirteen terminals. The original airport planners thought the airport would reach that maximum in 2001, but the airport is a little behind that number with only five terminals. The next one, Terminal F, is still in the planning and design phases.

Over the years, the airport has grown in other ways. The first hotel opened in 1974. The second hotel opened in 1981, but it was demolished to make way for Terminal D, which had a hotel incorporated into the terminal design. In 1994, the airport added two control towers. A consolidated Rental Car Center opened in 2000. Parking garages replaced the surface parking near the terminals. The airport also constructed new runways and extended existing ones to handle increased air traffic. The airport also incorporated cargo areas, as DFW became a major air cargo facility. Gone are the Airtrans system and the electronic signboards along the spine highway, which displayed arrival and departure information. They caused too many accidents, with people trying to read the signs as they drove to the terminals, so they had to be removed.

DFW’s decentralized terminal design was unique for the time and helped to make the massive airport more manageable, more human-scaled, and quicker to get to the gate. When you travel through the airport on your next trip, take some time to admire the design of the original terminals. The exterior remains relatively true to its original design, from the custom-colored exposed tan concrete to bronze solar glass windows. While upgrades and alterations have changed the interior, the exposed concrete modular structural members are still there, along with the ring layout for a division of uses within the terminals. When DFW opened, it was a marvel of planning, engineering, and construction. In sheer size, it eclipsed other airports of its time, and its layout ensured it could handle air traffic well into the new century, allowing for expansion without interrupting current operations. The airport still has room to grow to take us even further into the future, when who knows what kind of planes we will be flying.

All images courtesy of Braniff Airways Foundation.