EGO in the Arts

The complexities of urban density have long shaped Dallas, and with a spike in growth in our core, new issues have arisen. The story of Museum Tower has been covered extensively in this regard. However, there is another story in the making of a tower such as this. One much more insular to the development itself: The dynamic of the architect and the client, and the will they impose on each other.

Sitting in Klyde Warren Park on a tranquil spring day, I look up in the sky at Museum Tower as I have on many other days and admire its beauty. I am still inspired by the building’s gracefully sleek form four years after its completion. Lately, its elegance has been reinforced in the context of the articulating concrete frames of neighboring towers sprouting around within this newly shifted heart of the Dallas urban core.

It is not the tallest building in the city. It is not capped with a significant crowning element. It does not even follow the trend of wrapping itself in bright LED lights at night. The building frankly does not overly convey any real message of ego beyond its typology of that of a high-rise.

However, this beautiful expression from architect Scott Johnson, FAIA with Johnson Fain in Los Angeles has been documented locally and at a national level as the epitome of egotism in architecture. For nearly six years, the building has been caught in a quagmire regarding its curved reflective façade and the impact this has had on its neighbors within the Dallas Arts District—in particular, its effect on the Nasher Sculpture Center by Pritzker Prize-winning architect Renzo Piano, Hon. FAIA and landscape architect Peter Walker, FASLA.

Museum Tower also suffers the curse of systemic investment woes for the Dallas Police and Fire Pension Fund (the Fund), which is currently struggling with solvency issues on a national stage. The controversy is fueled by real estate investments undertaken speculatively rather than as completed performing assets.

While the focus in discussions on Museum Tower has been defined by these controversies, there is another tale within: the ego of architects who practice the process of design and the ego of clients who drive buildings to fruition. Now ego is a word typically carrying a negative connotation, but in the Freudian sense it refers to the portion of our personality that is rooted in conscious thinking and reason. The term is often used interchangeably with self-importance, but in reality it is much more about confidence and self-respect.

From its inception, and during the course of its creation, the Museum Tower project was touched by many talented architects and impacted by a cadre of great design firms. The story of these individuals and their roles in the process forms an important lesson not only on how we build our cities, but also on the humanity of architects working to make a greater built environment.

A Home for the Arts

The Dallas Arts District began as a result of former Mayor J. Erik Jonsson’s “Goals for Dallas,” the 1965 blueprint to develop Dallas into a more cohesive city and to take focus away from community’s self-conscious association with the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. In particular, a focus on design and improvements to the greater central business district outlined in “Goals for Dallas” was championed by architect Pat Spillman, FAIA and leaders within the architectural community. From this effort, the city of Dallas, with leadership from the arts community, began in 1976 to evaluate the development of a neighborhood cradled just within the border of the ongoing construction of Woodall Rodgers Freeway. Its initial purpose would be to house the recently merged Dallas Museum of Fine Arts and Dallas Museum of Contemporary Art.

The Dallas Arts District Design Plan, completed by Sasaki Associates Inc. in 1982 under the leadership of Mayor Jack Evans appointee Dr. Philp O’Bryan Montgomery Jr., provided an urban framework for a 17-block district. In early 1984, an anchor was established by the completion of the newly minted Dallas Museum of Art. Planning for the Morton H. Meyerson Symphony Center by architect I.M. Pei was well underway, opening nearly five years later. The development of LTV Center (now Trammel Crow Center), a 50-story office tower designed by Richard Keating, FAIA with SOM, was completed slightly prior to the Meyerson in 1985. Coincidentally, this tower challenged the idea of what would make a burgeoning arts district successful. The very nature of the proposed development created a heated argument that never subsided—even with the collapse of the Dallas real estate market in the wake of the savings and loan crisis.

With the district’s progress underway, Raymond Nasher, Hon. AIA desired to purchase the land upon which the center and its sculpture garden would eventually take shape. However, the site was owned by Trammell Crow and it took the city a threat of condemning the land in 1996 to bring resolution between Crow and Nasher. Ironically, it would be over 10 years after the completion of the first wave of construction before another institution opened its doors in the district in 1998: the Crow Collection of Asian Art, seated immediately north of Trammell Crow Center.

/ The Beck Group

Parking Lot Potential

That same year, architect Graham Greene, AIA sold the adjacent site and future home of the Museum Tower to John Sughrue and his development firm Brook Partners. A meaningful covenant at the time required limiting the height of any improvement to the site in respect to the forthcoming Nasher Sculpture Center to the southwest and the then nearly decade-old Meyerson to the northeast. More importantly, the covenant explicitly stated that, “..no reflective glass having a visible outdoor reflectance factor greater than 15% may be used on the building façade…where such glass would reflect onto the Nasher Sculpture Garden site, or the Meyerson Symphony Hall.”

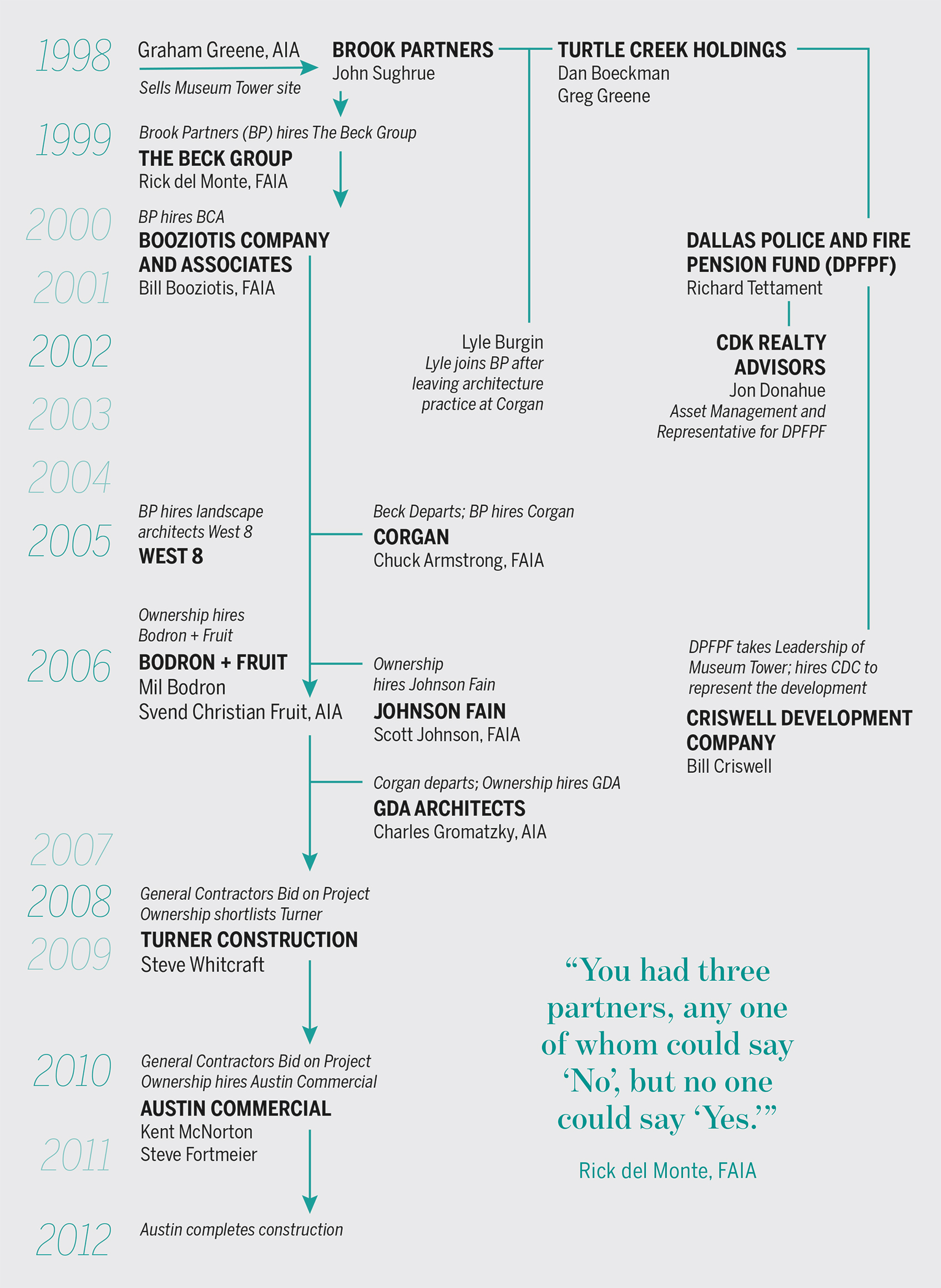

Sughrue purchased the land on speculation from Greene with the apparent intent to develop the most appropriate product for the space as Dallas began to recover from the collapsed development market. The site gained value with the pending potential for a signature building to house Nasher’s vast art collection, including an expansive exterior sculpture garden. After consulting multiple architects about how to best develop the property, Rick del Monte, FAIA was commissioned to study the site through an introduction by Brett Boaz, AIA, whose firm at the time, Turner Boaz, shared an office building with Sughrue. Del Monte was then a principal with Urban Architecture and is now the chief design officer at The Beck Group.

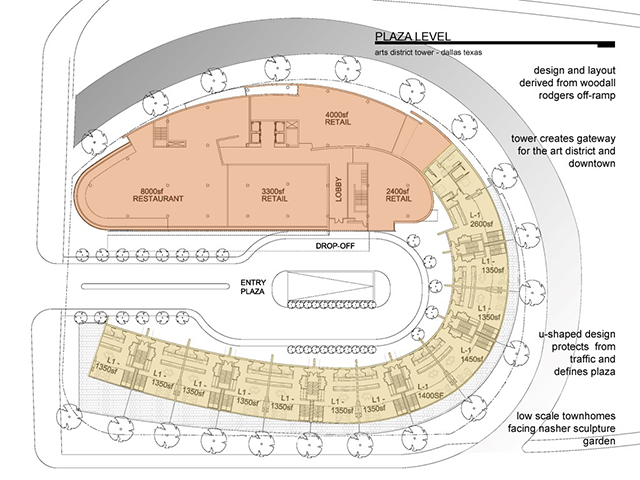

The initial concept plan generated by del Monte was an office tower. He knew that Nasher intended to develop a museum and garden, but few details were available. Says del Monte, “Fundamentally, my first thought was to get as far away from the future sculpture garden as we could. We pushed the building up against the property line. One side of the building followed the curved property line, the other side was flat with a courtyard.” The speculative project began to slowly test the market through the efforts of Sughrue.

Renzo Piano Arrives

The following year, Urban Architecture merged practices with The Beck Group, a story del Monte fleshed out for me when we sat down to discuss the history of the project. We met in the board room of Beck’s office, which offers a clear view of the Nasher Sculpture Center in the foreground with Museum Tower behind it. “My first day at Beck was November 1, 1999,” says de Monte. “I was told: ‘You have a meeting for the Nasher project. Renzo’s coming down and you’re the partner in charge. [Beck] is building it, and we are going to help them in any way we can.’”

He spent the following week consulting with Nasher’s design team, including Joost Moolhuijzen and Shunji Ishida, two of the architects from Renzo Piano Building Workshop. Piano arrived in the middle of the week. A site visit ensued with landscape architect Peter Walker and that led to Piano flipping the plan of the museum and the garden. Interestingly, this critical decision reoriented the design towards Flora Street and away from Woodall Rodgers Freeway years before the idea for Klyde Warren Park would begin to coalesce. This experience and involvement with the Nasher Sculpture Garden tempered del Monte’s future approach to designing the Museum Tower site.

The Client Develops

“Really, the Museum Tower was driven by the Nasher,” recalls del Monte. “If the Nasher Sculpture Center happened, then the Museum Tower project was going to move forward.” Indeed, as construction began on Piano’s design next door, Beck received the call to take Sughrue’s project in a new direction: a residential tower.

The desire for condominiums was driven by the involvement of the Dallas Police and Fire Pension Fund that saw the project as a worthy investment with great potential. The fund favored the curved scheme that Beck was developing, and Sughrue along with Brook Partners’ Lyle Burgin encouraged del Monte as well. Beck had little involvement with the fund, but as the project began to gain momentum, interest grew. The site for Museum Tower had originally been sold to Brook Partners with interest by Turtle Creek Holdings and its partners, Dan Boeckman and Greg Greene. Says del Monte, “At that point, the silent partners, whom I had never met, suddenly had no intention of being silent. Both Dan and Greg were heavily involved in the arts and this was a very important project to them. They wanted to make sure it was very beautiful.”

The resulting iteration of the design solidified the tower concept at 22 stories with a row of lowered townhouse-style units on the west side of the site. Early budgeting solidified this concept as a $100-million investment which the fund felt was appropriate. This was reinforced by a discussion between the ownership and Ray Nasher that pegged the building at topping out at its 22nd floor. “The size and budget all worked together,” says del Monte.

Passing the Buck

The dynamics had begun to shift from the development side and Beck began to lose clarity on designing the project. The situation grew more complex as Boeckman and Greg Greene brought another architect to the table to consult on the project: the late Bill Booziotis, FAIA. “Bill’s connection with the community may have been at the heart of why he was invited to be part of this project,” recalls Aaron Farmer, AIA. Farmer, an architect now at Omniplan, spent nearly 40 years practicing with Booziotis before closing the office with fellow principal Jess Galloway last fall. Neither Farmer or Galloway were directly involved with the Museum Tower project, but still were aware of it due to its profile and the role of Booziotis that morphed as the project matured.

Once Booziotis was brought in, friction began to develop due to the different design approaches for the building. Del Monte’s focus was driven strongly by the building’s urban impact; Booziotis was focused on the dwellings’ formalization and felt strongly that the curved tower designed by Beck was not appropriate. Booziotis also wanted a drive that circled around the building with a side drop. The results of his effort began to challenge locating the tower towards the east and moved it towards the center of the site. In recalling Booziotis’ style of practice, Farmer says: “The passion of the practice was really for spaces where people lived and those spaces had to bring a sense of satisfaction and delight and sometimes surprise and awe. The space had to be meaningful.”

Meanwhile, as the project evolved, the stress rose as well. Says del Monte, “I was put under really heavy pressure from Dan and Greg that we had to make this building rectangular.” Thus the building concept changed once again.

Beck neared completion of design development and was awaiting approval to move towards final construction documents. However, the project continued to veer off a singular course as Brook Partners, Turtle Creek Holdings, and the Dallas Police and Fire Pension Fund struggled to make decisions. “You had three partners; any one of whom could say ‘No’, but no one could say ‘Yes’ … Frankly, I did not have a relationship with Boeckman or (Greg) Greene,” recalls del Monte.

As the situation devolved, Booziotis seemed very concerned about the project and wrote to his client about the changes he felt needed immediate rectification. Without their implementation, he was willing to resign from the project. “I remember getting this letter on a Friday and mulling on it,” says del Monte. “Ownership panicked and became concerned that if Bill left they would be unable to sell any condominium units.” After consulting with company president Peter Beck and gaining his support, del Monte was ready to quit himself. “I was already not happy with the building. I recall thinking that it was an incredibly prominent site, and this is my reputation.” Del Monte recalls calling Sughrue that Sunday and delivering the news straightforwardly. He remembers essentially telling Sughrue that he didn’t feel he had the trust of the team, that he respectfully withdrew from the commission and that he encouraged Sughrue to find another architect.

A New Direction

Booziotis took ownership of the project with renewed zeal. Redoubling on his approach of driving the project from within, he focused on resolving the tower footprint. In contrast to the sculptural tower eventually constructed, Booziotis imagined a building that was an expression of the residences and of a more traditional form. Notes Farmer, “Bill’s passion was primarily for clients who were looking for very unique, elegant solutions, and not necessarily high-profile solutions. He was very excited about the possibility of the firm doing the major role of the tower, but it didn’t last long as I recall.”

While Booziotis was entrusted with the design for the time being, there was concern whether he had the staff readily available to document the project for construction. Ownership looked to Burgin’s friend and former partner, Chuck Armstrong, FAIA at Corgan to join the team. “Booziotis had done a new plan and we were brought onboard originally as the production architects,” says Armstrong. “I had a meeting with Lyle and Bill because, after del Monte, they asked Bill if he would do it. I don’t know if they had worked concurrently together or what exactly was going on. Booziotis just didn’t frankly have the manpower to put something of this scale together quickly.”

Armstrong’s team went to work extruding the new Booziotis floor plans in conjunction with a site plan concept from the recently commissioned landscape architecture practice West 8. Renderings were generated along with multiple site plan studies, but after six weeks passed the fund was unsatisfied. Their desire was for a more dramatic design—a signature building in the arts district. Burgin convinced his partners to let Corgan try designing the tower based on his own experience at the firm. Jumping into the role, Armstrong took an approach informed by Booziotis’ efforts to create a more formal floor plan, yet he generated concepts that were still sculptural in nature at the direction of the client. Interestingly, concerns of reflection and visual impairment of Nasher’s garden were never discussed during this time. “No one from the owner’s position ever mentioned, nor did we as architects discuss any impact the project might have on the Skyspace project [‘Tending, (Blue)’ by James Turrell].” Turrell controversially later declared the sculpture destroyed after Museum Tower’s completion.

Then came March of 2006. In full disclosure, I was a young intern on the project and briefly spent my time assisting in building models for a handful of prototypical designs generated by Corgan. Settling on a twin tower scheme, Armstrong presented a series of photorealistic renderings and images to the owners. The client immediately embraced them for their iconic, though less efficient, design potential.

Further muddying the role of Booziotis, Mil Bodron and Svend Christian Fruit, AIA were invited to join the project team. “Bodron and Fruit were brought on to explore the twin tower scheme unit plans,” recalls Armstrong. According to Farmer: “They were brought on to design standardized pre-built units. The work that I am familiar with that they did was to generate a standard set of plans and finish for pre-built residences. … Our role at that point would only be the occasional custom residence.”

The restructured team gained traction quickly with the new twin tower concept. Floor plans were developed further until they suddenly became hamstringed again by the client’s multi-interest dynamic. Enthusiasm waned from within and Armstrong was directed to design something even taller and more impressive. “There had been this groundswell at first,” says Armstrong. “One day they liked it and literally the next day someone along the way changed their opinion. It was an about-face and suddenly they couldn’t stand it and flip-flopped like a fish on a hot beach.”

Meanwhile, the pension fund had become increasingly convinced that the project was a “can’t lose deal.” Investing further in the project, they brought in another third party to the development team to represent their interests: Bill Criswell of Criswell Development Company. Criswell came from California where he had been consulting on investments made by the Fund all over the country. Interestingly, notoriety has been attributed to Criswell in the real estate community of Dallas. He infamously departed in the late 1980s after the market collapsed and a lawsuit was filed by Ross Perot in connection with the alleged mismanagement of funding between two projects. However, one of these projects—allied Bank Tower (now Fountain Place) by Henry Cobb, FAIA of Pei Cobb Freed & Partners—is arguably one of the most elegant and iconic skyscrapers of Dallas. It was clear to the design team that the project’s direction would now be heavily directed by Criswell’s presence.

After generating a, by then, much taller scheme, Armstrong became weary and wary of the project. “We were having meetings with [Criswell] and without anybody else. He asked us to work with Scott Johnson. Scott is a gentlemen architect, though he clearly wanted to come in and take over the job,” says Armstrong. Sughrue reached out to del Monte on his familiarity with Johnson. Says del Monte, “He’s a pretty good architect, but the main thing is that you need to have someone that you believe in, someone that you all think is a good architect and that your whole team is going to get behind and trust. Up to now, not with me, not with Bill, and not with Corgan have you all been behind anyone collectively and trusted them as the architect.” By the late fall, Corgan bowed out, formally resigning from the project in December of 2006. Shortly thereafter, GDA Architects—a prominent firm with extensive multi-family high-rise experience—was invited to join the team and assist Johnson Fain in completing yet another new design.

Go Big in Big D (or Go Home)

Scott Johnson had vision and he was the architect that finally understood what this client really desired. When asked by ownership what he would create if starting from scratch, he proposed being more ambitious with regard to the importance of the site. His ideas from the outset where driven by the importance of creating a beautiful object. Del Monte notes, “They were looking for a signature building. It worked with Scott’s vision and that is what they got. It hindsight, all of the [prior] various schemes were not grand enough.”

Johnson told the Architect’s Newspaper, “I was interested in doing something pure because the neighborhood is full of a lot of architectural testosterone.” The Fund fell in love with this position from the outset and doubled their financial commitment to $200 million. “Johnson Fain was successful because his champion, Bill Criswell, took control of the project as a singular entity and was given that authority by the Pension Fund, which had taken control from the original partners,” recalls Armstrong.

By June 2007, this poorly kept secret in the real estate community was finally announced and a proposed groundbreaking was planned by the end of the year. Advertisements for a 42-story, 560-foot-tall structure began to appear, but the market collapsed in the Great Recession before construction could even begin. It would be three years before the project finally became viable in a construction market that was hungry to build. Austin Commercial was awarded the project and broke ground in June 2010—two years before the building’s newly installed glazing changed the conversation on this controversial project altogether.

Reflecting on Museum Tower

Today, the debate and legal ramblings ensue over the way that Museum Tower’s glass façade impacts the integrity of Nasher’s art. The consternation of who is truly responsible for resolution is a debate that continues. Until the issue is resolved, the controversy will remain, potentially damaging both the quality of experience within the Nasher garden and the value of units in the Museum Tower. The project has been a case study both for Dallas urbanization conflicts and globally as the use of highly reflective glass, particularly on curved facades, increases. The intensity of the debate has left many parties sensitive, both to the impact on our city and in some cases their personal roles in the art district’s development. Many of the individuals contacted to comment for this article declared they were either not in a position to speak on the project or did not feel comfortable doing so.

Addled by ego rooted in the Dallas maverick spirit, Museum Tower succeeded on many levels while failing on many others—even with the best of intentions among its many competing owner voices. “It’s the conspiracy of optimism,” says Armstrong. “Human groups can talk themselves into something once they begin agreeing on anything. It happens with the best of intentions. The Museum Tower project gave me a keener understanding that it takes great clients to do great projects.” Similar sentiment was universally expressed among the architects involved with the project. Del Monte wistfully noted at the end of our conversation: “You realize what we do as architects in the design realm is so ephemeral that most clients can’t judge it. I look back in hindsight. For me, Peter Beck’s encouragement to walk away from the project was impactful.”

There are lessons to be learned from the numerous decisions an architect must make in the design process that are critical to its success. Museum Tower is a great example of how the ego of its many champions brought it to reality. The lessons it offers are invaluable to all who wish to better understand how we shape the built environment of our city.

Project Timeline

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2017 “Ego” issue of AIA Dallas Columns magazine.