The New Publicness

In a rapidly evolving urban landscape, the very definition of ‘public space’ is undergoing a profound transformation. This two-part series delves into how cities like Dallas are navigating the complex interplay of public ambition and private enterprise to create vibrant, accessible spaces for all. We will explore the dynamic spectrum of publicness, from traditional parks to innovative interior realms, and discover how imaginative design ideas could shape the future of Dallas’s urban fabric. The transformation of ‘public space’ in Dallas, characterized by the rise of public-private partnerships, represents a critical negotiation between needed private capital and the risk of democratic exclusion, requiring a deliberate commitment to equitable access.

I was recently reminded of the power of well-designed public spaces during a morning walk on the Katy Trail. The beautiful weather drew a diverse crowd, creating a vibrant and bustling atmosphere. As I walked, I noticed how seamlessly urban infrastructure can weave into the city fabric, exemplified by a particular moment passing through a space like the Rose Cafe at Le Passage. This seemingly residential building, with its ground level fluidly connecting street and trail, creates a soft threshold between a restaurant and a small adjacent park, inviting people to walk through, stop, and engage. This easy flow between seemingly disparate elements—trail, cafe, park—underscored for me how certain public spaces enhance urban life by fostering connection and movement, highlighting the vital permeability of urban spaces. It felt genuinely organic, prompting me to wonder how such places truly come to be, and what makes them feel so inherently ‘public’? It begged the broader question: In an era of evolving urban funding and development, what truly defines the ‘public’ in our public spaces, and how are these vital urban arteries conceived and maintained?

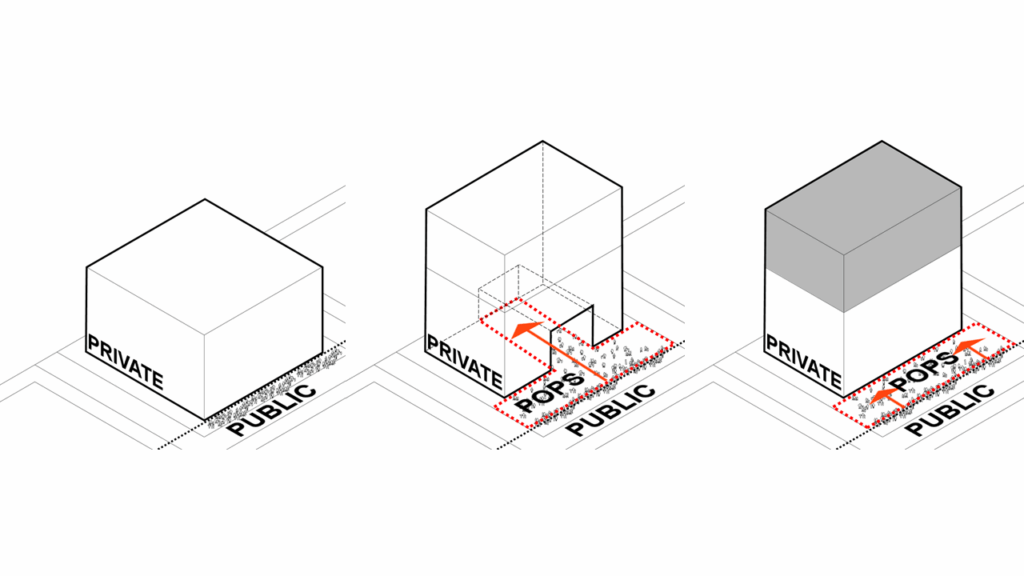

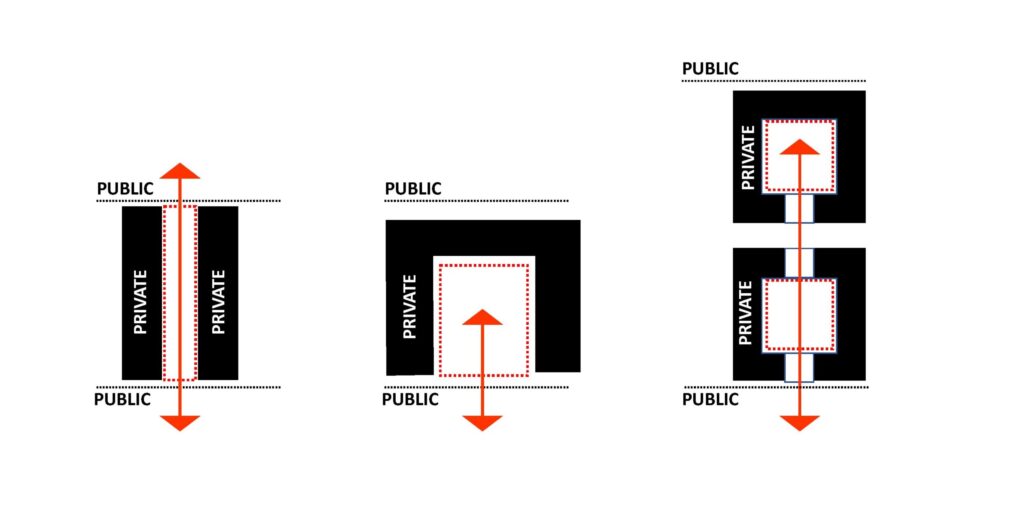

Urban theorists offer valuable insights into successful public spaces. Jan Gehl1 emphasizes human-scale design, walkability, and social interaction, principles seen in areas like the Bishop Arts District2. William H. Whyte3 highlights essential elements like seating, sunlight, and people-watching, features of successful spaces like the plazas around Thanks-Giving Square4. Jane Jacobs5 underscores social diversity, community, and safety, qualities fostered by vibrant neighborhood parks across Dallas. These perspectives converge on an ideal: A good public space should be accessible (like the linear accessibility offered by the Katy Trail), welcoming, comfortable (offering respite from the Texas heat), community-oriented, ecologically sound, and reflective of its surroundings. Achieving these qualities requires intricate collaboration and diverse funding models. While urban design theory elucidates the nature of good public spaces, the reality of their implementation often complicates the clear boundary between what’s truly public and what’s private, introducing a spectrum of “publicness,”. This intricate dance, often seen in concepts like Privately Owned Public Spaces (POPS)6, is where the idea of access frequently blurs with control.

The concept of “publicness” exists along a spectrum. At one end, cities wholly own, build, fund, and manage spaces with taxpayer dollars, giving the public a direct role as stakeholders. This model ensures the space remains truly public, accessible to all, and responsive to community needs. However, as cities face increasing financial pressures, they often turn to private sources for public space development and maintenance. This increased private involvement, while bringing significant resources, can lead to concerns about accountability and the prioritization of private over broad public benefit. There’s a risk that spaces may be sited to benefit more affluent areas or donor interests, potentially exacerbating disparities in access to quality public infrastructure between well-resourced and underserved communities, a concern voiced in discussions around development in certain parts of Dallas. This potential for unequal access and privatization is a serious concern, with global precedents showing how privately managed spaces can sometimes impose restrictions on activities like protests or public gatherings, often under the guise of security or maintaining order; thereby limiting fundamental rights of free speech and assembly. The balance between public and private interests is, therefore, a critical consideration in contemporary urban development.

Indeed, the most successful of these hybrid spaces often function as true ‘urban living rooms,’ blurring the lines between what is strictly indoor and outdoor, private and public, to create environments that feel surprisingly intimate and lived-in for the broader community. This spectrum is evident in Dallas. Klyde Warren Park7, a successful public-private partnership built over a freeway, demonstrates the potential for this model to create significant public value by connecting previously fragmented neighborhoods. Other examples of POPS and public-private partnerships in Dallas include West End Square8, a tech-forward park showing a new model for downtown activation; Carpenter Park and Harwood Park9, part of a broader downtown parks initiative leveraging both public and private funds; and the unique Dallas Water Commons. The ongoing development of Harold Simmons Park10 on the Trinity River, which was catalyzed by a massive private donation, also involves intricate collaborations between the city, private donors, and various stakeholders, representing a monumental future vision requiring massive public-private collaboration. Understanding the nuances of these partnerships is crucial for ensuring equitable access and genuine public benefit in Dallas. Each partnership model brings its own set of challenges and opportunities, and it’s essential to carefully consider the long-term implications for the community.

As designers, we operate within this fascinating dynamic, often representing both the private entity and the public good, the city and its citizens at large. It is through our innovative approaches that the challenges of balancing these interests can be transformed into opportunities for new typologies of public spaces. For such reasons, the study of the public-private relationship is so crucial for developing meaningful public spaces in contemporary times. The success of these spaces, however, hinges on a clear understanding of the spectrum of publicness and a commitment to equitable access for all citizens.

Ultimately, the question of what constitutes a “good” public space remains central. While the traditional view often centers on open parks, sidewalks, and the general public domain, the very definition, and therefore its typology, is expanding, especially as private involvement grows. The next essay in this series will delve into this expansion, exploring the increasing importance of interior urbanism and the blurring of boundaries as the public realm extends into buildings and other structures. This concept of urban interiority promises to create new forms of public gathering spaces, serving as an urban living room for the city. For ultimately, these urban areas are where cities and the people who live in them truly express themselves; they are the physical manifestation of collective values. As we collectively shape the future of our cities, a nuanced understanding of the spectrum of publicness, coupled with this broadened spatial perspective emphasizing soft thresholds and the permeability of urban spaces, presents a significant opportunity to create regionally distinctive and compelling urban spaces for Dallas

Endnotes

- Gehl, Jan. Cities for People. Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 2010. ↩︎

- Bishop Arts District: City of Dallas. “Planning & Development Bishop Arts.” City of Dallas. https://dallascityhall.com/departments/pnv/Pages/BishopArts.aspx. ↩︎

- Whyte, William H. The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. New York: Project for Public Spaces, 1980. ↩︎

- Thanks-Giving Square: Thanks-Giving Square Conservancy. Thanks-Giving Square. https://www.thanksgivingsquare.org/. ↩︎

- Jacobs, Jane. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House, 1961. ↩︎

- Kayden, Jerold S. Privately Owned Public Space: The New York City Experience. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2000. ↩︎

- Klyde Warren Park: Klyde Warren Park Conservancy/Dallas City Documents. https://www.klydewarrenpark.org/. ↩︎

- West End Square: Dallas West End Association. “West End Square.” https://dallaswestend.org/west-end-square/. ↩︎

- Carpenter Park and Harwood Park: Downtown Dallas, Inc. (Reference for Downtown Parks Master Plan). https://downtowndallasinc.org/. ↩︎

- Harold Simmons Park: The Trinity Trust/Dallas City Council Resolutions/Major Donor Announcements. https://www.thetrinitytrust.org/. ↩︎