Where the Stillness Grows

Photography by Sahana Ashwathanarayana

Photography by Sahana Ashwathanarayana

“Hindu philosophy is rooted in the belief that nature is divine, an expression and reflection of deeper truths calling for quiet contemplation, detachment, and ultimately, moksha (spiritual enlightenment.) Vastu Shastra, the science of architecture, blends elements of geometry, and design, guided by five elements (earth, water, fire, air, space) and directional alignments to promote spiritual well-being in built environments.“

I mourned the big tree I never had.

The tree that would have been a little way from my front porch, standing tall and singular in a field of grasses, its branches sturdy, where my father might have hung up a swing for me. The tree whose shade I would have sought solace in, running barefoot and wild with all the rage of a 9-year-old who has been denied a freedom she craved. The tree that would have been my sanctuary.

I grew up in urban Bangalore, far away from the quintessential rural landscape, where running out of my home to the nearest big tree would have included a long elevator ride to the ground floor and my parents’ explicit permission, and so I mourned the tree I never had.

As an adult, the longing for that sanctuary remained. Last fall, no longer nine but every bit as wild, I flew to Colorado with a half-formed idea: I’d find refuge under a big tree with the wind as my only companion. Arriving in Boulder, I found myself atop some red rocks, sitting cross-legged, pine trees around me. I spent hours there, soaking in the silence.

But the solitude I’d found was fleeting. Seeking quietness in the distance, as if it existed only in the far-off wilderness, is not a lasting solution. This was a privilege shaped by time, money, and the freedom to leave. If I couldn’t chase it, I had to learn how stillness could be created—solitude had to be practiced and carved out even in the middle of the city.

With Dallas as my testing ground, I sought to explore the intersection of my Hindu identity and my urban context. Through a reframed perspective of Hindu philosophy on nature, solitude, and spatial design, I began to ask: How can urban parks—places that are often far removed from nature’s sanctity—offer a place for solitude? How might design cultivate sacred moments within the bustling rhythm of urban life, inviting both spiritual and physical retreat? What role can nature play in this urban journey toward moksha, and how can it be integrated into the very fabric of our cities?

ALL GROVES ARE SACRED

“Each plant species carries unique meanings and evokes different moods that influence balance and well-being. Neem offers protection and purifies the air, while the sacred Ashwattha symbolizes continuity and divinity. Amra, or mango, is associated with spring and romance. Carefully consider the placement of each species for optimal spiritual and ecological benefits.“

In Hindu stories, forests often hold sacred groves, where sages meditate, where the rivers flow gently, and where trees are not merely trees but embodiments of the divine. These spaces exist outside the realm of daily life, set apart by belief, creating an atmosphere of quiet reverence.

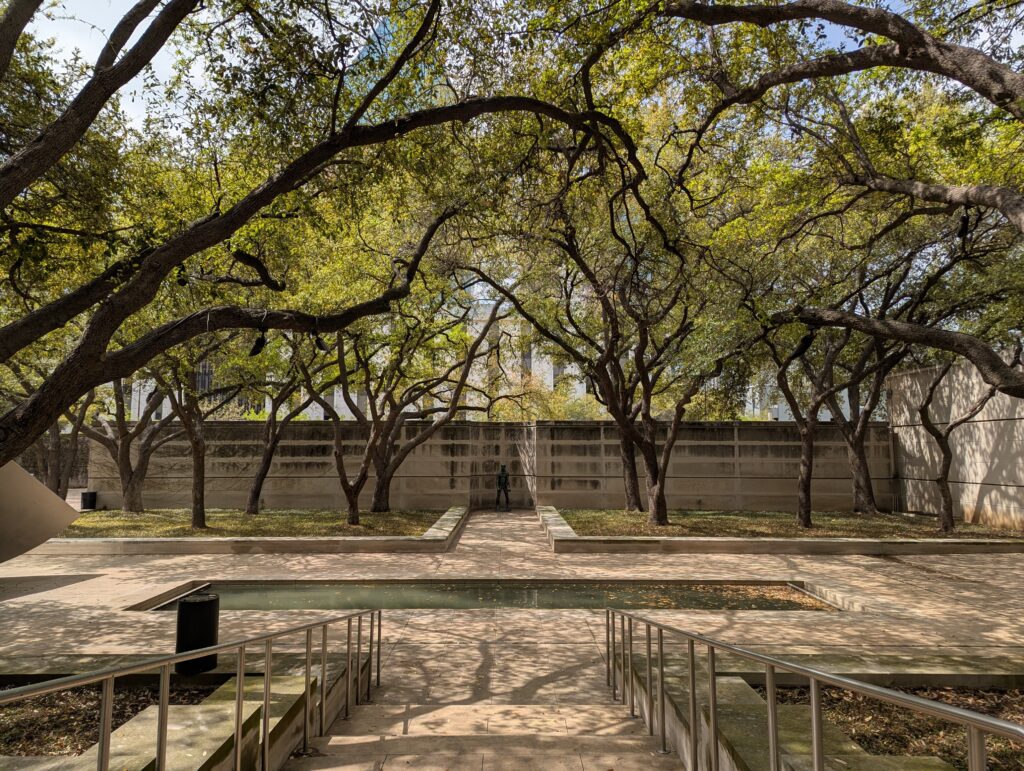

In the dense weave of a city, where every square foot is accounted for, it is rare to find spaces that can manifest sanctity. Yet, in Dan Kiley’s sculpture garden at the Dallas Museum of Art, I find an echo of these groves—an urban sanctuary shaped not by myth but by design.

The sculpture garden is a grid of live oaks laid out around a simple reflecting pool. The space is organized into several rooms defined by concrete walls—tall, shadowed only by the spreading canopies of live oaks beyond.

The trees are unequivocally the definitive elements here—their branches and leaves filter light and cast shadows on the ground and the walls. Live oaks are a symbol of quiet resilience. Beyond their ecological appropriateness, these trees carry a sense of timelessness. With their long lifespans and massive, spreading canopies, they evoke a stability and longevity even in this urban garden. Their symmetry lends a sense of order, and I know that these trees are the guardians of this courtyard.

There is a gentle breeze here, always. When it ebbs and flows, I feel it carries words of wisdom. In the dappled shade, sitting on a simple chair, I am enclosed but not confined, solitary but not quite alone. The garden is not silent; birds all around me are chirping, cawing, cooing, calling. The murmur of the museum lingers at its edges—but within its bounds, like the groves of old, it invites pause.

STILLNESS IN SEATING

“Vastu Shastra emphasizes the importance of balance in space, where the symmetry and evenness are key design features. Open central zones encourage flows, while boundaries create containment. Mental equanimity, even amidst external movement and chaos, is valued, enabling a sense of stillness in the midst of activity.“

Klyde Warren Park is one of the busiest public spaces in Dallas, where food trucks line the streets, joggers pass by, and children run across the vast lawn. Amidst the hum of conversation and the clatter of activity, moments of reflection may feel few and far between. Yet, in this very bustle lies a new interpretation of solitude, one that challenges the idea that it requires silence.

In fact, the park’s design invites moments of solitude because it embraces communal energy. The large lawn hosts picnics and games and also offers ample space for individual retreat. Trees line the perimeter, creating intimate, open spaces without forcing isolation. And then there are the movable tables and chairs, strategically scattered across the park, furnishing the opportunity for visitors to arrange their seating in a way that suits them. The ability to configure space to one’s liking reinforces a sense of personal autonomy, even amidst the crowd.

The benches are thoughtfully designed. Short enough to feel personal, yet large enough to accommodate two, they strike the perfect balance between individual comfort and shared space. The linear arrangement allows for quiet companionship—a side-by-side sitting that preserves one’s privacy without shutting one off from the world.

There is an underlying stillness that arises for those who seek it. Solitude in a public space like this is a learned discipline, a way to find peace in the company of others, and an intentional respite in the middle of the city’s rush. It works because the park’s design allows it, testing the boundaries between shared space and personal retreat.

GROUNDING THROUGH MATERIALITY

“Materials are not merely structural—they carry bhāva (essence). Stone, wood, and earth should be used in ways that honor their svabhāva (inherent nature). Unpolished, unpainted, or weathered surfaces reflect truth and invite stillness, grounding the built form in time, place, and spirit.“

To arrive at Beck Park is to descend—slowly and intentionally—into a space that feels carved from the earth itself. A path of bluestone interrupts the city sidewalk, catching the eye with its textured grain and muted hue before stepping down to the space below. Live oaks lace the edges of the lawn, and the sound of water punctuates the hushed silence within.

It is the materiality of Beck Park that defines its atmosphere. Bluestone, quarried in the Catskills, has now found its home in Dallas. The stone, like all natural materials, carries the weight of its history. Within the park, the large bluestone slabs give way to crushed stone. These tiny fragments, once part of a larger whole, come together once again to form a cohesive texture that unifies the space. Their presence becomes both grounding and expansive, an invitation to pause and reflect on the nature of being, on the passing of time.

Throughout, the design employs an honest expression of materials. Exposed concrete walls frame spaces without enclosing them. Wood benches are left untreated. Water emerges from a bronze spout and collects in a basin of crushed stone. Each element is allowed to do what it does naturally—shed water, gather patina, accumulate use. There is no narrative imposed on the materials; their integrity is what holds the space together.

The small moments, like the sound of water as it splashes into the pool below, or the scent that rises from the ground after rain—petrichor—remind me of my monsoon childhood in Bangalore. The park’s materials allow for personal associations to emerge, making it a haven where one might practice introspection. In the urban context, Beck Park ensures that quiet doesn’t require distance—with clear materials and minimal intervention, stillness can be designed.

THRESHOLDS: JOURNEY TO SANCTUARY

“Choreographing movement – transitions from narrow to open, dark to light, create a rhythm that mirrors inner transformation. Thresholds become moments of pause, guiding the body and mind toward stillness, presence, and ultimately, alignment with brahman—the universal essence.“

In many sacred practices, movement through different spaces often signifies a deeper shift in consciousness. Stepping into the garden feels like shedding the chaos of the outside world, leaving the noise of the city behind.

To enter Thanksgiving Square is to be welcomed into a deliberate spatial sequence that unfolds with every turn, every drop of grade. Corridors are narrow and tightened before leading to open, expansive rooms. This idea of enclosure before release is not accidental; the sharp contrast intensifies the spatial experience; these thresholds encourage us to leave behind distractions, to focus on the present moment.

Anchoring the plaza is the chapel. Ascending its spiral ramp is a different kind of movement—not inward but upward. The geometry of the path and the steady rise of the rainbow spiral of stained glass frame the experience as one of progression. The symbolism is subtle but effective—an ascent toward clarity, elevation, or simply quiet.

While these gestures may evoke spiritual metaphor, their impact is architectural. The sequence of movement, threshold, and light creates an environment that supports reflection, regardless of one’s beliefs. The space does not preach; it offers structure for contemplation.

A NOTE ON WATER

“Water, or jala, is an element of both nourishment and potential destruction. Its placement invites harmony when channeled properly. While water fosters balance between stillness and movement, offering emotional clarity and spiritual purification, it also holds the power to overwhelm, as seen in the deluge of Pralaya, symbolizing both creation and dissolution in Hindu thought.“

At the parks in Dallas, water is used as a spatial and sensory device to great effect. At Beck Park, the fountain’s rush is unmistakable. It flares and flows, breaking the silence with its loud presence. The scale of the feature is modest, but the acoustics amplify its impact. Here, water is not background; it anchors the experience, encouraging paying attention to the moment.

In contrast, the reflecting pool at the Dallas Museum of Art sculpture garden is static—still, dark, and contemplative. Like the sacred wells in a temple, it provides a visual and spatial pause, marking the garden as a place of inward focus.

Klyde Warren Park introduces water as play, with jets and sprays creating a social and interactive edge to the space. The water cools the plaza, animates the air, and encourages movement—its role here is to be restorative and joyful.

At Thanksgiving Square, water weaves through the perimeter of the garden in a continuous cascade along its walls. The sound creates a soft barrier against the city beyond, while the movement of the water introduces a subtle rhythm. The effect is cumulative: the longer one stays, the more the water recedes into the background, allowing the mind to settle. Its presence is constant yet unobtrusive—a condition that fosters concentration and ease.

Exploring Dallas parks through Hindu philosophy and the pursuit of solitude brings forth how, through thoughtful design, themes of materiality, tree species, water, thresholds, seating, and openness create spaces that honor sanctuary. As someone not expert in Hindu philosophy, I recognize that these ideas only skim the surface of a much deeper conversation about the intersection of spirituality, urban design, and the human experience. Even so, in the stillness of urban spaces, there is an opportunity to cultivate a deeper connection to the divine, nature, and ourselves.

Note From the Author: The boxed sections highlight ideas of Vastu and Hindu philosophy. These sections were edited for clarity and accuracy by Anusha S Rao, a long-time Sanskrit scholar and PhD candidate at the Department for the Study of Religion at the University of Toronto. Her research is focused on the intellectual history of Vedanta in early modern South India.