Can You Hear Me Now?

I began my teaching career at a Pleasant Grove elementary school in Dallas ISD during the spring semester of the 2014-2015 school year. My roster showed 23 third-grade students preparing for their first statewide standardized exam, the State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness. In years when there is no previous subject assessment (third-grade math and reading, fourth-grade writing, and fifth-grade science), there is no growth measure; still, the pressure of a pass-fail test was felt by students and teachers alike.

Our administration began requiring small group instruction in an effort to maximize the time in the classroom. The idea behind small group instruction is to allow students to work in smaller clusters so the teacher can have a better picture of what each child grasps in a subject. Then, using the data gathered in the small groups, the teacher devises individualized plans to close achievement gaps. Studies show that small group instruction leads to “particularly large achievement gains for participating students.”

Small group instruction provides the most engaging and efficient learning for students, but this comes at an immense cost of energy, effort and time for the teachers. Luckily, in the age of technology, algorithmic artistry equips teachers with the tools to shorten tasks to a fraction of the time. All teachers can attest that grading assignments is some of the most tedious work known to man. By my second year in the classroom, educational technology let me flash my student’s scantron answer sheet in front of my laptop camera and have a full diagnostic report in minutes. One program would even recommend small groups of students with similar answer patterns and pair a lesson plan for their lowest standard. But while technology has revolutionized classroom teaching, what good is the invention of a dam to those who live in the desert?

The problem was not lack of resources. In fact, the wealth of in-depth, often free online resources was at times overwhelming. Programs like ThinkThroughMath and Reasoning Mind – now both housed under Imagine Learning – interwove gaming and math instruction to eliminate the intimidation behind practicing difficult math concepts. Also, these programs put students on their own track based on their specific achievement gaps. Automated programs were having a teacher’s assistant who could meet with my students one-on-one.

The frustration came from the impossibility of getting those resources to my students. In my classroom, there were five desktop computers, including the one on my desk. Rarely were all five operating simultaneously. During my five-year tenure at this campus, I never had a class where at least half of the students had access to internet speeds or devices capable of handling the functions of these online curriculum supplements. They only had the 45 minutes of my small group rotation schedule to use the online curriculum. By no means does technology replace all that a teacher is in that room to those children, but if dependable, technology expands their reach. The district curriculum came with an online supplement, but without access to high-speed internet, the students in that community essentially got a diluted dose.

This was five years before March 2020, when the global COVID-19 pandemic forced K-12 education to be entirely remote for the first time in United States history. In that 2019-2020 school year, I was employed at a private school in South Dallas. Even though we were not yet 1:1 with computers in the classroom, all of my students had devices and high-speed internet at home. The students were required to complete a certain number of online lessons each year as well as a weekly technology class. So, while being 100% virtual was completely new, computers were not foreign. Teaching remotely is not ideal, but those students were proficient enough to get the most out of the experience.

For many students in Dallas, the pandemic marked the first time they had internet access in their home. It is quite unfair that they finally get this access while their computer literacy is directly correlated to their academic success.

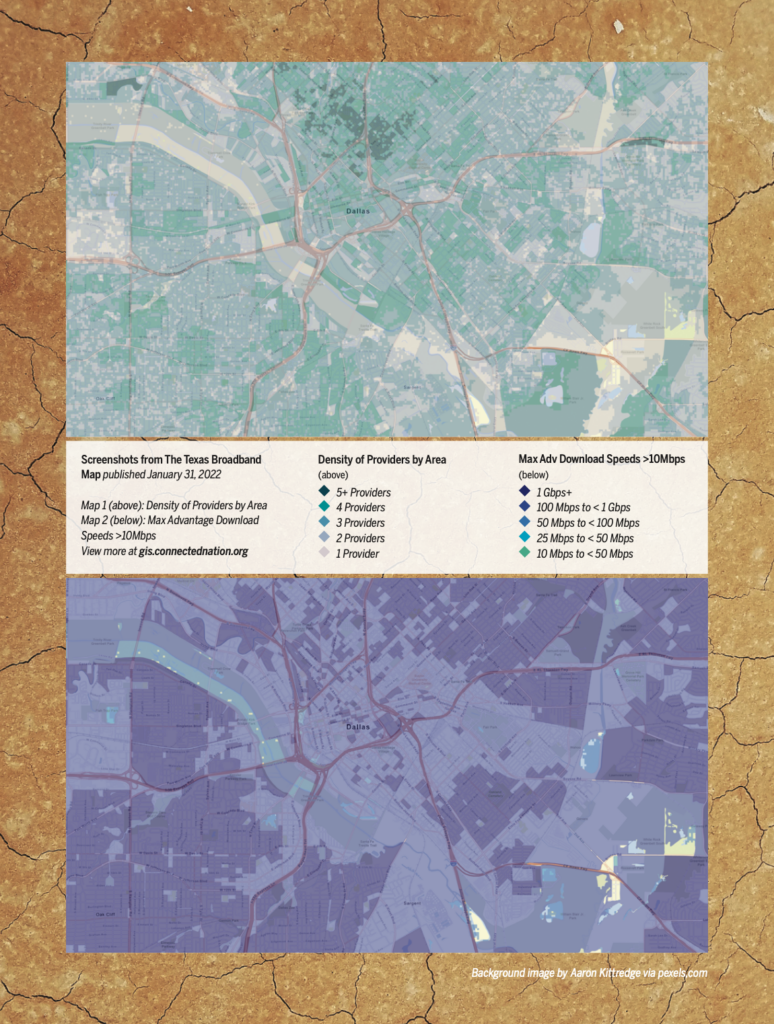

Dallas County Commissioner J.J. Koch authorized a report that showed Dallas County was among the worst in the nation for access to high-speed internet. Some data in this survey showed three of every 10 Dallas County homes didn’t have access to the 2010 standard of broadband.

For reference, the average download speed of 2010 was 4 Mbps. The average download speed in 2021 was 100 Mbps. How can students excel when they barely have enough bandwidth to get their lessons in high definition?

A year and a half online equated to consecutive years of learning loss for many students who did not have the proper equipment or experience in the home.

Access to high-speed internet has been essential for residents, let alone students, for at least the last five years. The pandemic put a spotlight on the glaring differences in experiences for students solely based on their ZIP code and download speed.

Lawmakers have brought attention to these digital deserts. Texas House Bill 5 was passed on June 15, 2021, which established the Broadband Development Office, or BDO. According to govtech.com, BDO will be “responsible for creating a broadband map that reveals which areas are eligible for financial support, setting an established threshold speed for underserved areas, participating in community outreach, and acting as the subject matter expert to support local governments with funding opportunities.”

This is not something that will be corrected overnight because it did not become a problem overnight, but there is plainly a need for improved connectivity throughout Dallas. Technology can only be the academic leveler we champion if all students have a chance to access it.

Original photograph by Rachel Claire via pexels.com

Photo illustration by Frances Yllana