Grace Note: Addition to the Stretto House

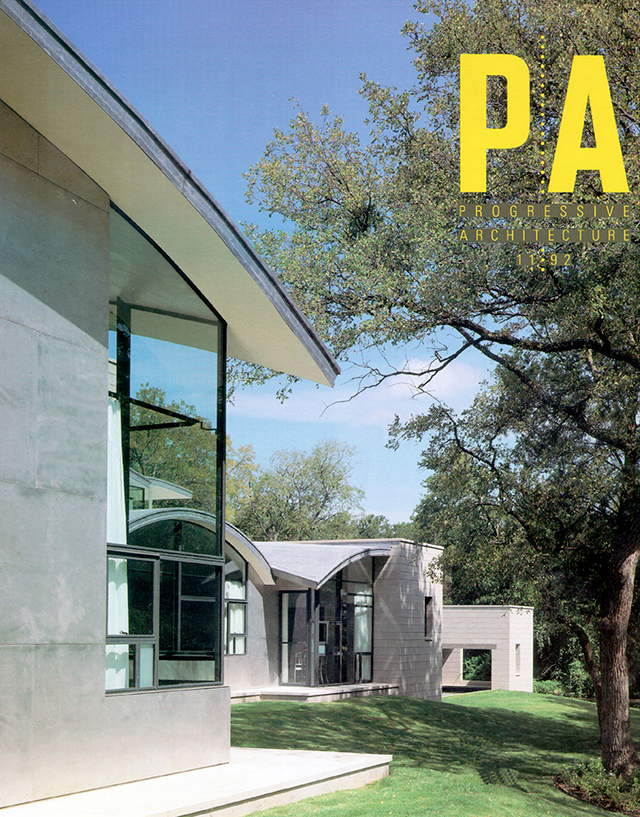

Driving slowly down Rockbrook Drive in Dallas, a motorist can catch tantalizing glimpses of the Stretto House through the lush foliage. The house — commissioned by descendants of Harold Price, who built Frank Lloyd Wright’s Price Tower — is considered a canonical work in the career of Steven Holl, FAIA, AIA Gold Medal winner. Soon after its completion, it received a national AIA Honor Award in 1993, a monograph published by Monacelli Press in 1996, and a place in the collective modern architectural consciousness.

The architecture is defined by a lyrical roofscape sheltering the living spaces, punctuated by four lineal concrete block forms containing the utilitarian spaces. This composition metaphorically echoes a creek that parallels the house and flows over a series of old concrete spillways. The alternating light and heavy construction also evoke the musical form known as stretto.

I was fortunate to be the local associate architect on this fascinating project. As I viewed the exquisite ⅛-inch scale schematic design model (made of concrete and copper), I was asked to recommend a local structural engineer and a general contractor. Given the ambitious design, the architectural team worked early on with nationally esteemed Thomas Taylor of Datum Engineers and Thomas S. Byrne, the contractor who so admirably built the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth.

A couple with children bought the sprawling two-bedroom house a few years ago. Needing three more bedrooms, they asked me to design an addition. I advised them that because the Stretto House has such an artistic signature, only Steven should do it. But they did not want to work long distance with his office in New York. I discussed the matter with Steven, and he supported me accepting the challenge.

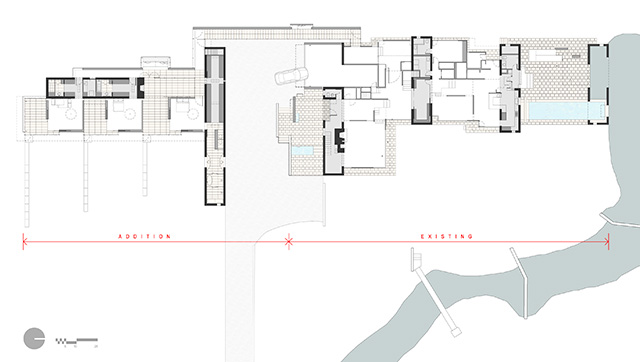

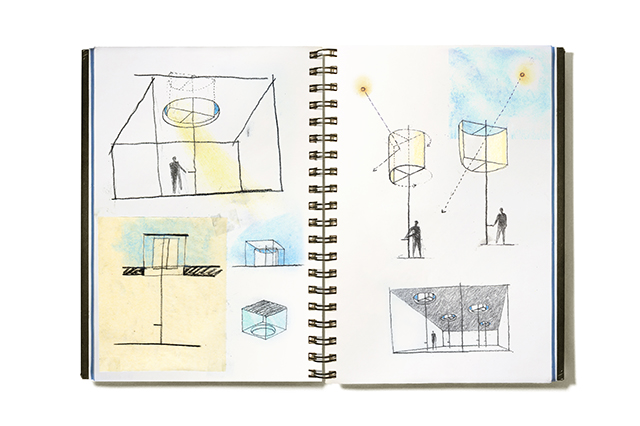

How on earth does one add on to a tour de force? I decided to do so quietly and at a distance. The addition is stem-mounted to the house by a long, slender, glazed gallery and cut into a slope to remain low and visually defer to the expressive house. Being distant from the creek, the addition’s roof does not repeat the metaphor of water flowing over spillways. At the same time, we did not want the addition to be without a spark of life. A series of cylindrical glass light monitors, each equipped with a “light sail” shading device became the grace note.

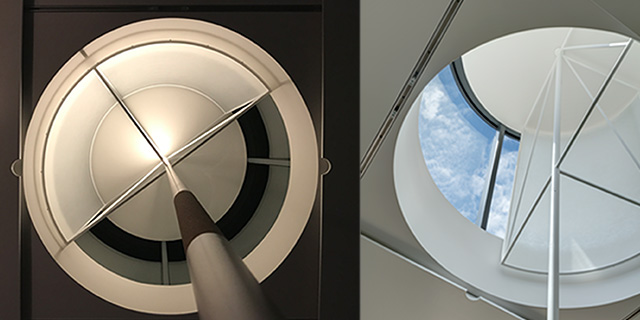

Each light sail consists of a 1½-inch diameter steel mast running from a ball bearing fitting at the floor to the ceiling of the light monitor. At waist height, there is a cork grip by which the mast can be easily turned. Atop the mast is a framework of half-inch-square steel tubing clad in Lumasite, a non-yellowing translucent plastic resembling rice paper. The light sail can be manually pivoted to redirect sunlight in the summer or admit sunlight in the winter, with many other positions in between for milder days. Grasping the mast, gazing upward, turning it or even just the light sail’s presence itself can bring to mind the sun’s immense journey and the passage of time. At night the sail and glass cylinder are illuminated like an enormous lampshade by a ⅜-inch-wide LED strip-light milled flush into the mast. During thunderstorms, a pair of sliding ceiling panels can be closed manually with a custom cork-tipped rod stored on a nearby wall mount.

These light sails arose from the combination of my sketchbook, the meticulous craftsmanship of James Cinquemani, the lighting acumen of Steven Byrd of Byrdwaters Design, and the superb general contracting of Hardy Construction. Oh, and one more essential ingredient: a generous and trusting client.

Max Levy, FAIA is the founder of Max Levy Architect.

Images projected by Charles David Smith, FAIA

Project Credits

Architect: Max Levy, FAIA, principal; Matt Morris and Tom Manganiello, Max Levy Architect, Dallas

Contractor: Stephen Hardy, Hardy Construction

Interior Designer: Emily Summers

Light Sail Craftsman: James B. Cinquemani

Lighting Designer: Byrdwaters Design

Structural Engineer: Datum Engineering