Dallas Goes Underground: Fallout Shelters for Survival

Subscribers to Life magazine received their Sept. 15, 1961, issue showing a startling cover picture of a man in a “civilian fallout suit.” Headlined “How You Can Survive Fallout,” it also touted a letter from President John F. Kennedy inside.

That letter was an ominous one in response to the escalating tensions in the world, warning, “Nuclear weapons and the possibility of nuclear war are facts of life we cannot ignore today.” It said the government was working to improve protections for Americans by surveying all public buildings for fallout shelter potential. Those that qualified for shelter status would be marked and stocked with food and medical supplies in case of a nuclear attack.

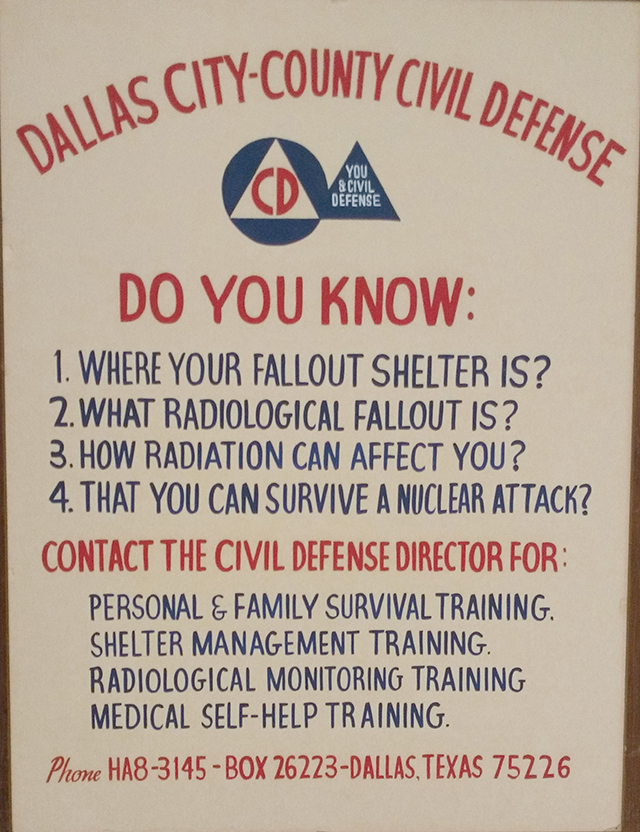

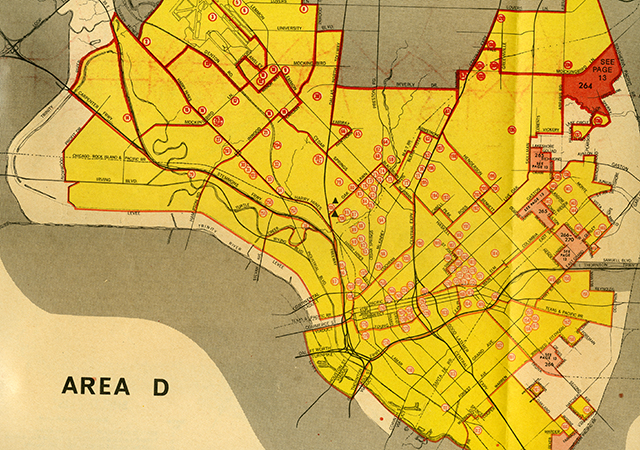

Dallas joined the survey effort under the auspices of the Dallas Civil Defense Office. A 90-day survey of buildings, conducted by three companies, began in January 1962 in Dallas County. Photo-sensitive cards recorded 128 items of information, then were sent to Washington, D.C. and analyzed by special computers. The firms hired to complete the building survey were Forest and Cotton; Hennison, Durham, and Richardson; and George L. Dahl. Dahl was in charge of the buildings in the downtown area, which had 200 of the estimated 350 buildings eligible for the survey in the county.

According to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, to receive federal designation as a fallout shelter, a building had to provide at least 100 more times protection for a person than being out in the open and have enough space for 50 people. The shelters were not intended for people to survive a direct hit from a bomb but rather as a place to escape to in case of a blast. The idea was that after people were alerted to an imminent attack, they would have just enough time to get to a shelter, where they would be protected from the cloud of nuclear fallout arising from a bomb blast nearby. Scientists at the time said people would need to stay in a shelter for two weeks before the radiation would decrease enough to make a safe exit.

By May 1962, the survey was completed, finding 381 buildings in Dallas County eligible to serve as public fallout shelters. With minor modifications, an additional 132 would meet the requirements. In downtown Dallas, about 100 buildings were identified as approved shelters. They were mostly in basements, although a few buildings had shelters on higher floors. Those containing official fallout shelters included the Adolphus Hotel, City Hall, Dallas Memorial Auditorium, Dallas Public Library, the Kirby Building, Lone Star Gas, Majestic Theater, Mercantile Bank, Neiman Marcus, Southland Life Insurance Co., the Statler Hilton, Tower Petroleum and the U.S. Post Office.

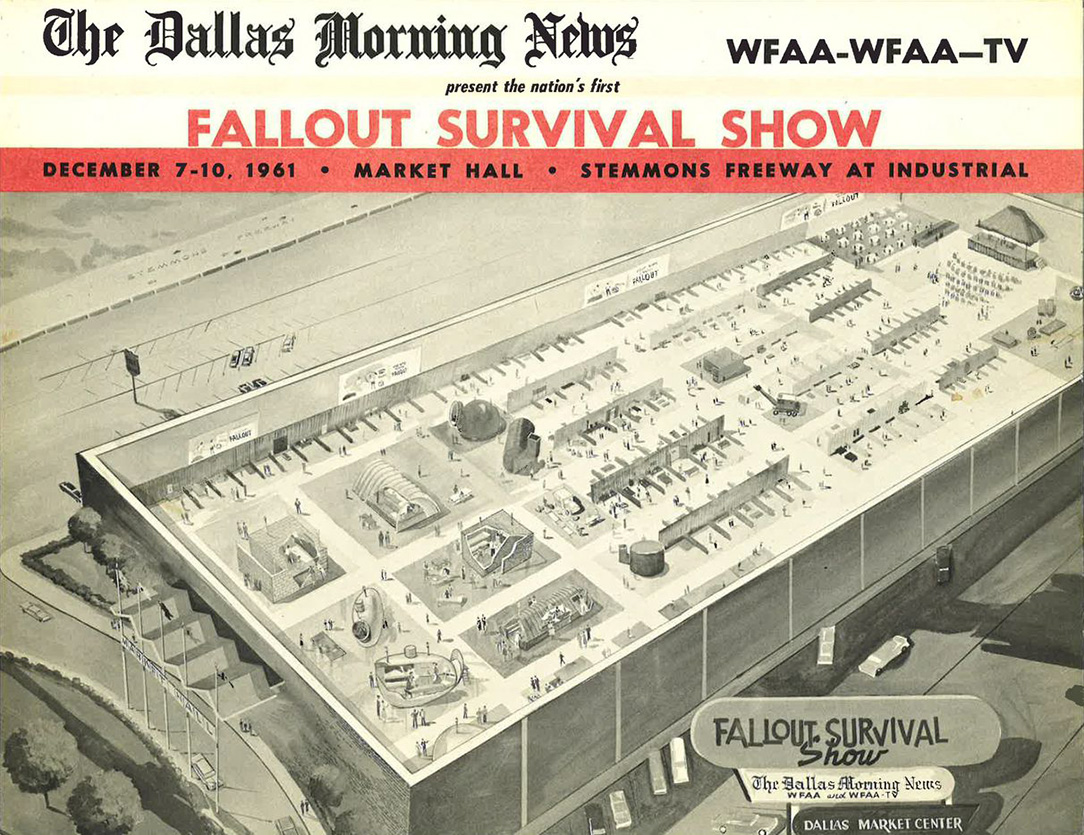

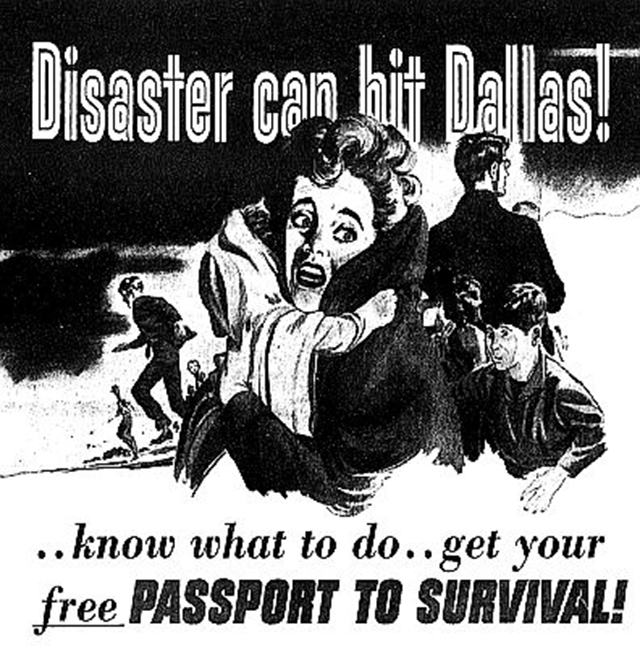

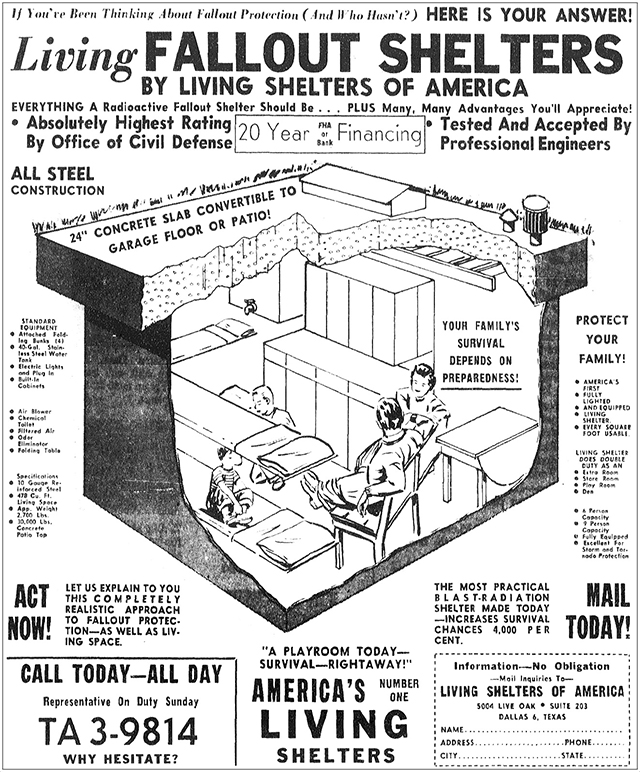

A couple of years earlier, a campaign had been launched to encourage the construction of private fallout shelters. In 1960, the State Fair of Texas displayed a model fallout shelter to persuade people to construct or install one of their own. A few months later, the first Fallout Survival Show in the country was held at the Dallas Market Hall, beginning on Dec. 7 – a date strategically chosen as it marked the 20th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The four-day show, planned by The Dallas Morning News, Dallas Market Center, and the Women’s Auxiliary to the Dallas County Hospital District, cost $1 to attend. The News touted, “One hundred eighty-six booths offer all sorts of new materials, information, equipment – even educational and inspirational tools – having to do with nuclear attack.” A number of fallout shelter builders showed off their concrete, steel, and fiberglass models, available as do-it-yourself kits all the way up to fully assembled units ready for installation. New companies sprang up to build and install the shelters. Even pool builders, with their expertise at digging and building in the Dallas soil, got in on the act.

Dallas residents jumped on board with building or installing their own fallout shelters. Many were built in backyards across the city, although there is no clear record of how many were installed. New subdivisions also spotted an opportunity; Happy Hollow Homes in Grand Prairie advertised it would build fallout shelters for families occupying its custom-designed, three- to four-bedroom split-level houses. “The fallout shelters offer Happy Hollow families protection from harsh weather and radiation fallout, in the event of nuclear war,” its president said. The shelters, located in each section of the subdivision, would serve 20 families apiece.

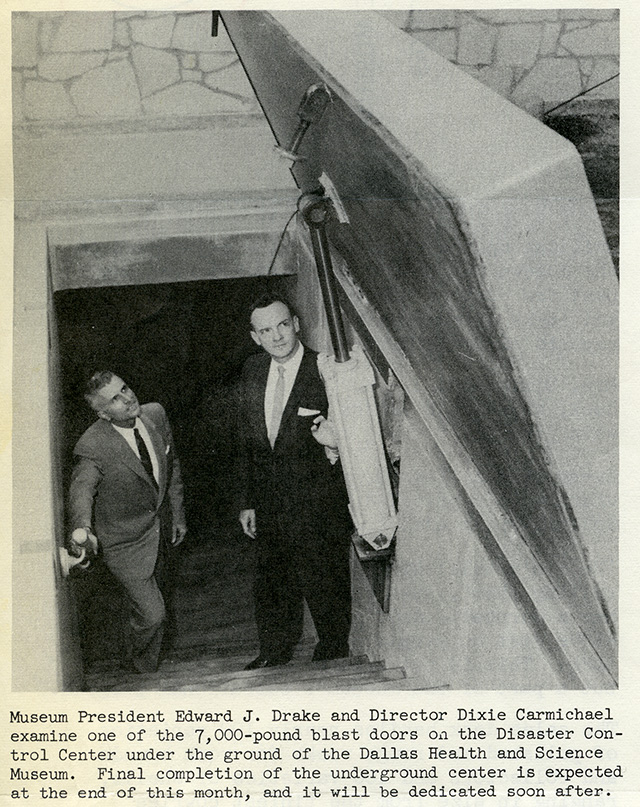

In case of a nuclear attack, there had to be a centralized command center where public officials could maintain important emergency operations and coordinate recovery efforts. The Dallas Civil Defense Emergency Operations Center (EOC) served that purpose. But it was not built underneath or near City Hall but rather at Fair Park next to the Health and Science Museum (former Science Place Planetarium). Construction of the EOC took place from 1960 to 1961 at a cost of $120,000, with half borne by the city and half by the U.S. government.

The EOC was more than a fallout shelter. It was actually a blast shelter with concrete and steel blast doors operated by hydraulic lifts over the entrance stairs that could seal off the interior and protect occupants from a direct bomb blast. The EOC’s air ventilators included “anti-blast valves” that could close the system to prevent blast pressure from entering. An air circulation system occupied a large mechanical room with a wall of filters, which would remove fallout contaminants from air entering from outside.

Communications to the outside world during an attack would have been key. A communications room held radio equipment for workers in civil defense, fire, police, sheriff, water, hospital/medical, streets and sanitation. The mayor and public information officials had their own combined office where messages could be broadcast to the public. The operations room was the largest space, designed as a gathering place for the different departments to coordinate and respond to an attack. It contained desks, tables and chairs, and chalkboards; large maps of the city and county covered the walls. Separated by folding doors, the room connected to an area where radiation effects (RADEF) could be monitored via radiological stations around the city. The EOC also housed a small dormitory, separate bathrooms for women and men, and a kitchen.

The exterior blast door is still visible outside the museum, along with the anti-blast valves and venting equipment. Thankfully, the EOC was never used for an emergency, and over time it became a storage area for the museum. When Science Place closed, the contents of the EOC were removed, and now it is no longer accessible.

The threat of nuclear war in the early 1960s was top of mind for Americans across the country. The U.S. government addressed those fears by coordinating efforts to authorize fallout shelters across the nation and to encourage citizens to build their own if they could. As nuclear tensions eased over the years, the fervor for shelters waned. Eventually the federal government stopped stocking the approved fallout shelters with supplies, but the distinctive fallout shelter signs are still visible on buildings across the city. Now they can serve as shelters during weather events. The shelters may have been a way to provide some protection from fallout, but how much is unknown. And after two weeks in a fallout shelter, what would occupants have faced after exiting? Would it really have been possible to survive and rebuild their lives? Fortunately, we never found out.

David Preziosi, FAICP is the executive director of the Texas Historical Foundation.