In Search of a Sacred Order

One of the things many of us tell ourselves when deciding on an architecture career is that we don’t do it for the money. Rather, we do it for profound reasons, for purposes that transcend a mere concern for social status, financial independence, or material comfort.

To be financially viable, our job requires the development of specialized technical competencies that can be adequately compensated. But it is well understood from the outset of our education that these competencies must serve a grander purpose, one that elevates the act of building as not just providing shelter for a given function, but also to manifest our view of humanity, nature, and even the metaphysical.

The what, as represented by our profession’s expectations of technical proficiency, means nothing without the why. It is not enough to understand what we do, but why we do it. In an ideal world, each of us should nurture and promote a system of beliefs, a knowledge of reality that informs our design and the technology used to buttress it.

What constitutes these beliefs, what are their sources, and do they matter?

For most, nature is our primary source for knowledge in how we invent ways to adapt our structures to it. In exchange, the structures we create express humanity’s relationship to nature. The latter generates a set of principles that embody a worldview that, early on, assumed the presence of a divine power that governed nature. The first known architects were priests who consulted sacred scripture on the design of temples, tombs, and cities. Nikos Salingaros, a professor in the College of Sciences at the University of Texas at San Antonio, reminds us that the human desire to understand nature led to religion, which then began to codify how humans should respond to it.

Architects should play an essential part of this codification. Salingaros says: “Traditional religions arose from nature and developed guidelines for keeping a society healthy. For example, dietary laws that seem strange to us actually protected followers from diseases in the original climatic setting. The core belief of an architect should be commensurate with responsibility and dedication to living structure.”

All rights reserved.

Architecture was seen throughout much of our history as part of the sacred order, and a designer was expected to perceive and contribute to it. Without this kind of reverence to a greater power beyond ourselves, whether in the form of god or nature, the individual becomes the source of order.

This acceptance of a higher order and putting it into practice was very much the role of architectural theory. Architects provided a summary that defined the world from a coherent perspective and offered a corresponding approach to design. History shows a long tradition of architectural theory, beginning with scriptural sources of the first civilizations and achieving a more detailed and technical treatment during the ancient Roman era in Vitruvius’ Ten Books on Architecture. Although Vitruvius neatly encapsulates the balance between technical problem-solving and the visually transcendent, his famous dictum that we should consistently strive for firmness, commodity and delight is preceded by the assumption that the architect must practice personal virtues as embodied in the state religion. Thomas Noble Howe, a professor of art history at Southwestern University in Georgetown, TX and co-author of the most recent English translation of Vitruvius, explains what the great Roman engineer meant: “The architect should act in accord with the divinely established principles of nature, which is pretty much a type of religion. Also, he really believes you should consult the gods (augury) before doing anything. His recommendation to check the livers of sacrificed animals who lived on the site you are considering makes sense: The liver is the most sensitive organ of the body.”

Learning the classical orders and carefully analyzing the site should not deviate too far from sacred ritual, since the realities of nature are revealed through them. Since Vitruvius, a broad theoretical education is a fundamental part in forming architects. Theory continued to evolve, with various people referencing, expanding upon, reinterpreting, and re-examining Vitruvius.

With the arrival of the European Renaissance, the prevailing beliefs shifted from a god- and nature-fearing point to the worship of individual genius, best exemplified by Michelangelo. Before this juncture, the artist (and architect) had little social status, expected only to carry out works that followed tradition and catered to the patron’s taste. Now the artist was seen as a vessel of divine inspiration, to the point that the value of his work relied less on technical brilliance, which there nonetheless was, but in the fact that the individual himself created it. A cult of genius took hold in all of the arts, and the works of these celebrated figures became part of a visual canon that led to the core of design education. This growing library of great works provided valuable precedents in solving architectural problems specific to changing times, but it also instilled a heightened emphasis on the value of the individual over a prevailing sacred order.

This tension between a reverence for nature and its sacred order and that of the individual would break down as the 20th century began. Right before this change, the prevailing education paradigm (originated at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris) consisted of training designers in the cumulative technical and planning knowledge from antiquity to the present day and in the assimilation of a grand architectural canon. Being well-versed in classical detail and proportion was to acknowledge the transcendent order of nature inherent in timeless works in antiquity. This order was manifested in beauty or aesthetic delight — ideally independent of anyone’s unique imprint.

This notion began to dissolve at the onset of World War I, as the quest for beauty and delight was de-emphasized in favor of secular socio-political and technical priorities. Beaux Arts wisdom, derived from a long tradition of comprehensive treatises and essays, gave way to dry and distilled manifestoes that relied on bold critiques of the status quo and a call to action to implement dramatic social change. Reform became urgent after the destruction of war, and past solutions no longer applied to new problems. Innovation was needed, and a reliance on individual genius would become its main source. With the German Bauhaus school, a new educational model arose that tapped into this call, eliminating references to the past and encouraging exploration through experimentation and self-reflection.

However, the public spirit of the Bauhaus, as well as all other architecture schools that it subsequently influenced, masked an essentially individualistic perspective to problem-solving. It elevated the person to the status of a hero whose sweeping vision promised a universal solution to all problems. A new pantheon of architectural gods emerged, with a sort of religious worship for individuals such as Frank Lloyd Wright, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, and Louis Kahn. Pretty soon, architectural education devolved into producing designers who treated a set program as merely a vehicle to project the prevailing aesthetic styles championed by their preferred god.

Students now believed that it wasn’t enough to reveal God’s transcendent order through buildings, but instead it was better to become a god creating designs inspired by the gods they studied. A modernist canon formed to justify the new truths; it served not necessarily to enlighten students but to enforce a strict social order over them. The teacher-student, or master-apprentice relationship, always harbors the potential to turn into cultic one, particularly in a studio environment. Duo Dickinson, FAIA, a widely read architect and educator from Connecticut, expands on this further: “Inside baseball cults of personality, defensive manifestations of common fear avoidance make lemmings of the young that become social movements. Those movements become cults when the aesthetics of their origins become polemic and holistic canon. Architecture is said, by many, to have a canon that is easy to describe as ‘modernism’ but in truth is more about the narcissistic ego as manifest in elitist vision: that ‘my way or the highway’ basis of our present canon means the ossification of diversity to the status quo, where the various cults of personality like Wright, Soleri, and Gropius have been subsumed into a stultifying Canon of the Now: Modern, Correct, and Unquestioned. Diversity has become a uniform cultural good, but it has largely vanished from the Canon of Architecture.”

Consider the common motivations of those who pursue a career in architecture: to seek proximity to one’s gods at school and hopefully in an internship; to go on a dedicated pilgrimage to see an otherwise obscure building; to practice the virtue of self-sacrifice; to redeem the world with one’s own vision of the good. These goals give architecture the trappings of a fleshed-out religion.

For the increasing number of people who have abandoned religious faith in favor of more secular alternatives, architecture can provide a pseudo-religious lifestyle complete with its clergy (starchitects, professors, critics), faith in the promise of enlightened design by learning from its assorted deities, a system of seminaries and monastic centers that cultivates an exclusive priesthood promoting the right kind of practice (the universities, starchitects’ offices), a gnostic indifference to outside public opinion, and yes, even approved attire to indicate group membership (all-black attire, neckties, horn-rimmed glasses).

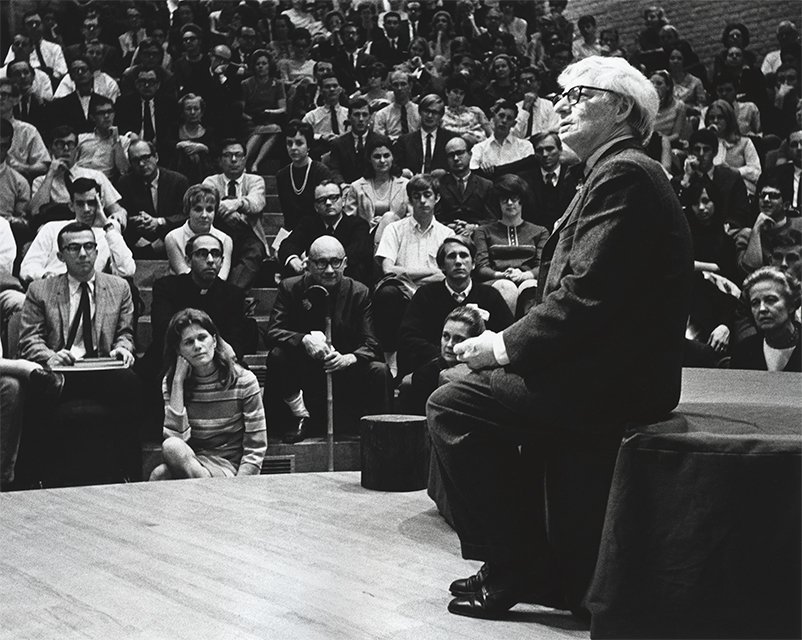

Courtesy of Menil Archives, The Menil Collection, Houston, Photo: Hickey-Robertson

In other words, if one is not careful, one can make architecture into a cult, a group defined by philosophical beliefs in a particular person or goal. Even the theory they are commanded to learn has a socially isolating effect akin to cults, as Salingaros articulates: “Architectural theory since early modernism is insular, having protected itself from outside scrutiny and any scientific validation. In fact, what has been taken for theory for decades is a cleverly developed technique for brainwashing. After reading all that stuff during the years spent in architecture school, the students’ minds are rewired so that they can no longer perceive the geometry of nature or their own sensory signals. Fashionable but inhuman forms are imprinted into their brains, so any design ideas that come out are simply regurgitations of implanted images. This is classic conditioning as practiced both in the military and in religious cults.”

This pattern of near-religious devotion to individuals and an eagerness to join groups centered around them and their ideas enables a tremendous amount of suffering and abuse. From offering to work many uncompensated hours at the office, spending sleepless nights at the studio, submitting themselves to public humiliation at reviews, sometimes it seems that there is no limit to how much someone will degrade themselves for the opportunity to gain the approval of a professor or a design principal. Many people outside the architectural field would view this prevalent pattern of self-imposed hardship as masochistic. But to those within this culture, it is evidence of the virtue of self-sacrifice, where the chance to create requires complete focus to uncover a deeper reality. It’s a kind of martyrdom that is self-fulfilling. Dickinson declares that “martyrdom in the arts can be seen as justification for devotion. If you love enough, the fruits and reason for that love are simply assumed as being natural. If you try to understand or replicate or defend beauty, you have missed the essential point of simply experiencing it — even in its design.” Sometimes devotees get so carried away that they fail to experience the joy of what they’re doing.

In addition to harming a person’s physical and mental health, extreme self-sacrifice can lead to the predations of sociopathic teachers and design leaders. The supposed virtue of selflessness can have perverse results in a student’s education and ultimate happiness, as Salingaros further explains: “It’s not selfless self-sacrifice, but the submission necessary for belonging to a strange religious cult. The biggest sacrifice is that the young architect subjugates his or her own visceral reactions and accepts only the approved images handed down from the ‘great masters.’ This is not a noble attitude at all, although that’s how young architects justify it to feel good about themselves. It’s in fact the opposite: the attraction of power and the promise of exerting dominance over large constructions, without much thought given to the eventual users of their buildings. Architects seeking power are willing to go through the harsh cult initiation rites to join the system that will permit them to exercise this immense power.”

This heavy dedication to belief over all else harms not only individuals within our profession, but also negatively affects how we are perceived by people outside it. It presents architects as aloof, mired in esoteric jargon and tuned out from the actual concerns shared by the public. Architecture is primarily the art of solving complex problems involving the needs of users. But the fixation on expressive form and a convoluted rationale to defend it contribute to the public’s view that architects play mostly a peripheral cultural role — necessary only for building sculpturally iconic structures but of little use for modest, strictly functional projects.

When modernist pioneers urged architects to abandon the practice of composing facades with classic motifs or cobbling together different vernaculars in favor of a new engineered-base aesthetic, the results were left wanting. Bauhaus’ experiments in social housing and the technocratic urban proposals from the Congrès internationaux d’Architecture moderne (CIAM), or International Congresses of Modern Architecture, would result in soulless postwar cities crowded with out-of-scale concrete residential towers and cold glass facades. A secular ideology had replaced the sacred order, leading to a spiritual dead-end. And yet, through it all, the public expects architects to instill in their creations a sensitivity toward form, materials, and function.

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

After the collapse of the sacred order, unleashed egos and cultic social patterns in our schools and design studios, where are we now? The mode for deconstruction that has defined the post-modernist reaction since the 1960s has played a major role in demystifying the universalist monolithic doctrines of modernism and their most famous advocates. With its emphasis on relativism and a penchant for irony and humor (“less is a bore”), post-modernism partially restored the importance of the past as a valid source for architectural inspiration. Its nihilistic underpinnings, however, would prevent the restoration of a traditional religious sacred order, but architects are now free to subscribe to as many belief systems as they wish. In our post-modern age, truth is subjective and increasingly a personal matter. The self has replaced the outside authority figure as the ultimate guru, and the leaders we revere are those who promote self-love among their admirers. Unlike previous generations, many people today are averse to seeking or embracing a belief system that ignores the importance of self-esteem.

Another factor in the diminishing cult of the hero architect has been the emergence of a hyper-competitive market economy. Architectural services are a part of a ballooning construction and engineering industry that is global in scope. Firms with more than 1,000 employees continue to multiply, while even larger engineering giants acquire those firms in the pursuit of growth and satisfying their shareholders. Other than their usual mission statements of “making the world a better place,” there is no interest in promoting philosophical doctrine, ideology, or in elevating individuals to sage-like status — unless those things cleverly elevate the brands of these firms. Likewise, it is easier to understand the phenomenon of starchitects in the context of brand identity than in the articulation of a comprehensive worldview for others to follow. Individuals such as Bjarke Ingels, Zaha Hadid, Hon. FAIA, and Frank Gehry, FAIA retain their own personal yet highly sophisticated theories about form, the environment, cities, and society, but all their ideas form and maintain a signature design style that creates the brand that their status-conscious clients seek.

So does belief matter? Can faith in a sacred order still be relevant in practicing architecture? In our current era, it appears that a materialist faith would prevail, whether in technology, commerce or the superficial power of iconic forms, often closely tied to belief in one’s ego. Despite these, we search for a set of ideas that allows us to design something that instills joy, wonder, and even harmony. Buildings should embody a love for the people who occupy or live around them instead of coercing them to accept a novel yet brutally alien environment. Beyond being rational program-solving machines, buildings are also emotional machines, and we judge them as much by how they make us feel as how well they work. The ancient ideals for firmness, commodity, and delight still apply since they are driven by precisely this primordial human longing for what our structures mean to us.

There is a spiritual dimension to what we create, and it serves for many as the primary motivation for design. Dickinson describes this idea of spirituality further: “The spirit is simply what gives joy without reason: love. Not the sybaritic joy of inebriation, passion or sensory thrill, but in the deep rewards of emotional connection to the well of love we feel for infants, the sea, the sun, life; the reality of beauty that we do not create or control; it is a near mystic truth of value that compels devotion: that has meant profession, I think it may come to mean Mission.” Achieving that mission requires that we focus on the quality of the work and its emotional effectiveness and not on the individual responsible for creating it. The love that connects us to a place should also translate into a love for the well-being of others, so our designs should further that purpose. This requires restoring the sacred back into the design process. Salingaros summarizes it this way: “An architect has (and ought to swear to) a sacred purpose, to help create a healthy, healing environment for all users. This attitude requires a faith in the goodness of humankind and acceptance of the existence of a higher form of order.”

Even if we all agree to jettison the pseudo-religious trappings that seem to linger and damage many individuals in the architectural academy and profession, it doesn’t mean following some kind of creed isn’t valuable. What form should this creed take? Salingaros offers a list of beliefs, influenced by best-selling author Christopher Alexander, that could provide a valid starting point: “We could begin a wonderful new healing architecture if architects started to follow a moral purpose. That would include: Respecting the geometry and mechanisms of the physical universe. Respecting the geometry and mechanisms of biology. Respecting the structure and needs of the human body and the human sensory system. Promoting the future of the human race by designing appropriate environments for children. Respecting the incompletely understood yet historically vital connection between material configurations and the sacred.”

This creed involves understanding who we are as humans: a rational and emotional creature limited by biology that is an integrated part of a larger, more complex natural reality. For those who would prefer a simpler, more intuitive creed, Dickinson is more succinct: “Listening, seeing, creating, understanding – in that order.”

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2019 “Belief” issue of AIA Dallas Columns magazine.