Experiencing Sight

In a previous article, we explored how to design a community center around a public restroom as the project focal point of the project brief. This article explores the design process when designing for people of various ages who are blind or have low vision. The featured project in this article is Enchanted Hills Camp and Retreat located on 311 acres on Mt. Veeder, ten miles west of Napa Valley, California. Enchanted Hills Camp has served the community of blind children, teens, adults, deaf-blind seniors, and their families since 1950. Owned and managed by LightHouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired, the camp provides opportunities for recreation in a safe, fun, and accessible environment.

Helen Schneider, AIA of Perkins&Will San Francisco and Chris Downey, AIA of Architecture for the Blind discuss their work with the Lighthouse for the Blind, from process through post-occupancy. The conversation magnified how to center the user(s) during design and decenter the architect. The goal for designing for people with disabilities should go beyond prescriptive guidelines provided by the ADA Standards for Accessible Design and above the principles of Universal Design without abandoning them or including them in design as an afterthought.

In 2017, a large portion of the Enchanted Hills redwood forest and camp facilities burned in the Napa Fires. After the fires were extinguished Lighthouse for the Blind hired Perkins&Will San Franciso Studio to assess the damage and generate a comprehensive rebuilding plan. With climate and fire resilience in mind, the master plan came together through hands-on collaboration with blind and low-vision individuals. The new facilities go beyond replacing the outdated facilities that burned with purpose-built buildings and site improvements. All constructed spaces, both indoor and outdoor, are required to comply with building codes, and ADA guidelines are non-negotiable. But how does the architect go beyond compliance and foster dignity in the process and execution of the work? Aside from the building code and ADA guidelines, there are no prescriptive methodologies when designing for people who are blind or have low vision.

Enchanted Hills required the design process to focus on safe navigation, tactile expression, and auditory solutions. These may not apply to projects when vision impairment or lack of vision is not part of the user experience. When you can see, you are not always concerned with how a space feels under your hands, and cross-modal perception is not the way most sighted people experience a space to ensure their safety. Both touch and sound become important in spaces for the visually impaired user, but how can this be achieved by promoting confidence in someone as they move through the space?

Helen and Chris’ responses below challenge us to go against the false illusions of bestowing dignity and empowerment upon the user and demonstrate how the user can inform how we think to expand our practice.

Editorial review provided by Lauren Neefe.

What does a dignified design process mean to you?

Helen Schneider (HS): A dignified design process to me, means we as architects do not have all the answers and our most important role is to listen and learn from the lived experience of those who we are designing with and for.

Chris Downey (CD): Specific to this project it is exceptionally important to admit not knowing everything when it comes to something radically different from your own lived experience. It is good for an architect to go through a process like this because you become more empathetic because you must rely on other people’s experience to work through not only the initial process, but during documentation and through punch-lists. The process for this project ideally will allow not only experience to be gained, but hopefully allows architects to establish some practices, procedures and understandings that can carry forward into other projects.

When initiating this project, did dignity come up as an explicit or implicit design driver?

HS: The word dignity was not used as a descriptor or discussion topic, but as a concept, it was absolutely a driver. Brian Bashin, CEO of Lighthouse for the Blind was explicit at the start of the project that we were actively listening and learning from blind and low vision people who were central to the project visioning.

CD: With this client, our antennas were always up, keen to listen to and understand their experiences and requirements. Dignity was inherent in the process from the beginning without it being explicitly stated. The design team would not have won the project if the Client, during the interview process, did not sense that the temperament, skillset, and mindset of the team understood dignity in the process that was needed to inform the outcome of the built work.

Can you tell me what some of the process entailed, survey of future users?

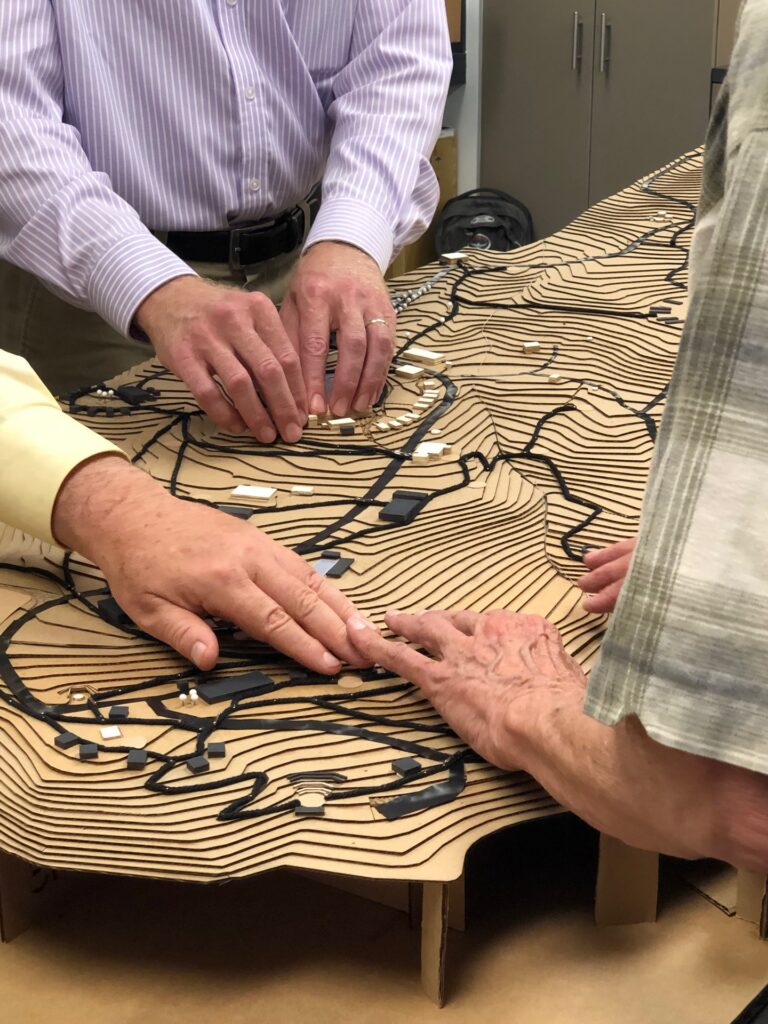

CD: Expanding on process, as architects we are fond of saying our drawings are our currency. Enchanted Hills Camp is a sort of deviant, the client cannot access drawings and models the same way sighted clients can. Lighthouse for the Blind has a media and accessible design lab where they were able to take the standard drawings and create what equates to a braille floor plan. This lab is typically used to make documents accessible for low vision and blind people, having the ability to use the lab to make architectural drawings accessible allowing participants in the design process to fully engage is a game changer for the industry.

HS: We started working with Lighthouse for the Blind after the 2017 fire to develop the master plan. In 2018/2019 we created a tactile topographic model of the masterplan, which took several iterations to construct in a way that allowed the client to use touch to understand the site. This allowed them to level changes in the site and distinguish new versus existing buildings – this was a successful endeavor. 2020 happened and all our in-person engagement meetings suffered because we were unable to meet communally.

CD: Right, 2020 made the design process harder because you cannot ship multiple tactile site models to the team and talk them through the design on Zoom. You cannot feel the screen to read the drawings, you cannot stand in community to ensure we are all talking about the same thing because the physicality of the experience is lost, and all of that has a ripple effect. While we were able overcome these obstacles, we had to do so with a higher level of care and engagement.

Do you think the ADA guidelines and Universal Design speak to dignity or strict functionality in lieu of the qualitative experience?

CD: Simply put yes – true accessibility regulations are about functionality and safe engagement with the physical environment. ADA is prescriptive and can be seen as the accessibility extension of the building code. Universal Design is intended to bring in the qualitative, but even within its seven principles it does not. Universal Design speaks to equity and perceptible information, but it’s almost between the lines and you must dig deeper and have more of an interpretative attitude to bring the qualitative experience out of it. We should not design in a reductive way, using the tools and mechanisms to meet dimensions and clearances while simultaneously minimizing or restricting the human experience. With Enchanted Hills Camp the qualitative experience leaned towards a broader sensory experience of being in nature and not just functionality of utility – that is the idea of dignity.

HS: For many architects their introduction to designing for disabled access inclusion is done through the building code and the ADA guidelines and it is done in a prescriptive manner. It becomes an exercise of meeting the numbers and at times the humanity of the design is left out. The merger of the two is more effective resulting in a more holistic solution – yes meet the functionality, but also fully consider the human experience.

Construction is now complete; will you complete a post-occupancy evaluation, and do you think it is useful? Do you think the design feeds into the user’s sense of dignity and confidence on the campground?

HS: Absolutely, this summer (June 2024) will be the first time the facility will be in full operation, and we will be able to see if it is being used the way we envisioned or otherwise. I have been in communication with Tony, the camp director, and he walked me through the plan for the summer. Throughout the summer and fall, the camp will flex between camp programming for blind and low-vision campers, retreat rental to support vital blindness programming, and volunteer groups. I am excited to visit a variety of sessions to observe and ask questions of the campers and retreat, and volunteer, participants.

I recently did a punch-list walkthrough with a Board Visioning Committee member who is blind, and he brought up several items that could only be observed as construction closed out and commissioning occurred. He brought to my attention items that might seem insignificant to a sighted person but can be injurious to someone who is low-vision or blind. For example, our specifications called for milled aluminum strike plates. It’s typical for these to stick out 1/4″ with a radius curve. In some cases, these had rough edges that can turn into a hazard when you must use your hands to ensure that you are getting to the threshold of a door. We made the repair to smooth the edges to avoid injury, and we addressed items as they came up to ensure safety for all.

CD: Helen’s walk-through hits on an important point, she is sighted, and her companion was not, that feedback from what a sighted person sees during a punch list is vastly different than what a low vision our blind person will experience. When you can see – you can choose what to focus on as you move through space and that affects what you pick up on -sight impairment does not allow for that.

From the blind experience, it is not until you come into physical contact with a space that you experience it. And how many times does it take to pass by something until that precise sort of event or less than perfect alignment or movement around something brings you into contact with your environment. And just because one person goes through and does not pick something up does not mean another person will – their immediate paths of engagement will be different. In summary, it will take time to get feedback. Between the punch-list and post-occupancy evaluation the feedback will be important to address immediate needs but also it will aid in informing future designs responses to a project brief. In our profession today, whenever you are doing something for people who are the outliers of what is typically considered within the norm or typical life, the post-occupancy evaluation is an opportunity to capture lessons, that is missing in our profession today. What lessons can we pull from that are relevant elsewhere, that just makes the environment better for everyone or can make it more inclusive for people that are blind that maybe are of little consequence, but maybe actually contribute towards the experience of everyone.

What does the client want all architects to consider when designing with dignity and do you think this is something that we should be taking more about?

HS: We should be speaking more about dignity in the design process before we begin to develop a concept in response to a brief. While there are many things that we know as architects based on our training, there is so much we do not know. We should always aim to listen and resist our impulse to push something aside based on educational, professional and our own lived experience.

CD: We are trained to think we have the right answers but by embracing that which is different and being open to suspending our disbelief it makes our work better. I have come to appreciate the term used in our conversation, dignity, because it is explicitly different from inclusion or accessible. Dignity puts more meat on the bones in terms of what we should be creating space for in our practice. It is more specific than just being inclusive, we are creating spaces for people, and we must acknowledge their humanity, their value, and their ability to contribute and belong. A sense of dignity should be the foundational aspect to our work, a sense of dignity becomes a sense of belonging and that drives the sense of inclusion.

Image provided by Perkins&Will. Part of the Dignity in Design series.