Irving Convention Center

Photo by Leonid Furmansky

Photo by Leonid Furmansky

Toward the end of 2023, I met my friend Leonid Furmansky, an Austin photographer, on the second-floor terrace of the Irving Convention Center. Here, the upper volume of the convention space rises overhead to a dramatic point where the structural and copper forms weave together, casting shadows where the ramps and terraces meet. Considering the scale and heft of the Irving Convention Center’s massing, this creates an intimate moment among a collection of expressions that together give the building a complexity and purpose rare in Texas. And “it’s in Irving f-ing Texas,” Leonid says bluntly.

When we both were assigned to cover the Irving Convention Center 10 years prior — Leonid for the curated image archive Divisare and me through Texas Architect — the landscape of Las Colinas was dramatically different. There is no better documentation of the convention center during that time than Leonid’s set of photos from 2013. His images capture moments throughout the exterior terraces, showing a rather empty Las Colinas that seemed to be waiting for what was next. One hallmark trait, found in nearly all the photos, shows the terraces bathed in the Texas sun as they look out toward an expansive horizon, with an occasional peak of a Las Colinas glass office tower from behind. Even with the increased development around the site, the impact of the sun remains.

The horizon view captured by Leonid, with the Irving Convention Center set on its own, conveys the building’s iconic statement, a form that looks as if the strata of the Texas bedrock was lifted out of the ground below only to remain in stasis. “The shape of the Irving Convention Center looked like a world-famous building without knowing anything about it,” Leonid says. “Though it’s a modest and informed flare, the clarity of the building’s statement was the draw. This could have been done by a famous architect, but you learn that it was designed by a smaller American firm.”

That American architect, Barbara Hillier, was “often challenging the status quo through her approach,” Bob Hillier, her husband and business partner, said. “Barbara was the brains behind the building.” In many respects, the Irving Convention Center is the defining work of her career, representing the height of her ability to challenge not merely for aesthetic value but rather the meaning that a project can convey upon its surroundings and, more important, its community.

Bob points to the Becton Dickinson Campus Center in New Jersey as a key example of Barbara’s boldness. The company wanted an employee center linking two portions of the campus. The conventional approach would have been to build a structure above grade that could open out to the landscape. However, “management and research were not talking,” Bob said, and Barbara strongly believed that such a move would erase the importance of the lawn.

With a sketch idea, accompanying the expected approaches the client initially sought, Barbara proposed a 38,500-square-foot facility embedded thoughtfully into the landscape. “Rather than sacrifice the lawn, the building is beneath the lawn,” Bob said. “We successfully preserved the sanctity of the open space between the main buildings,” forming a gathering space known as the Great Lawn.

The Irving Convention Center was also intended to be a catalyst, one that would inform a new masterplan framework for Las Colinas. Beyond acting as an anchor for the northwest corner of the district, the convention center site needed to define key edges that would render the program capable of drawing development in toward the site. The earliest stages of master planning called for a series of single-level conference spaces sprawling across the landscape, a “typical approach for a six-acre, flat-boxed convention center design,” Bob said. “When Barbara got a call to design it, we defined a series of influences” that the approach to the convention center needed.

Barbara focused on the value of the land area through conservation. Finding a more efficient way to organize the convention center would result in creating increased value for development, as well as the benefit of gaining landscaped, public spaces around the convention center, a rarity in projects of a similar type. Another consideration was the former wetlands that Las Colinas sits upon. “It was critical that the foundations were given enough stability, where piers had to go 50 to 60 feet below grade. A vertical form would help focus the structural intent without again compromising more landscape,” Bob said.

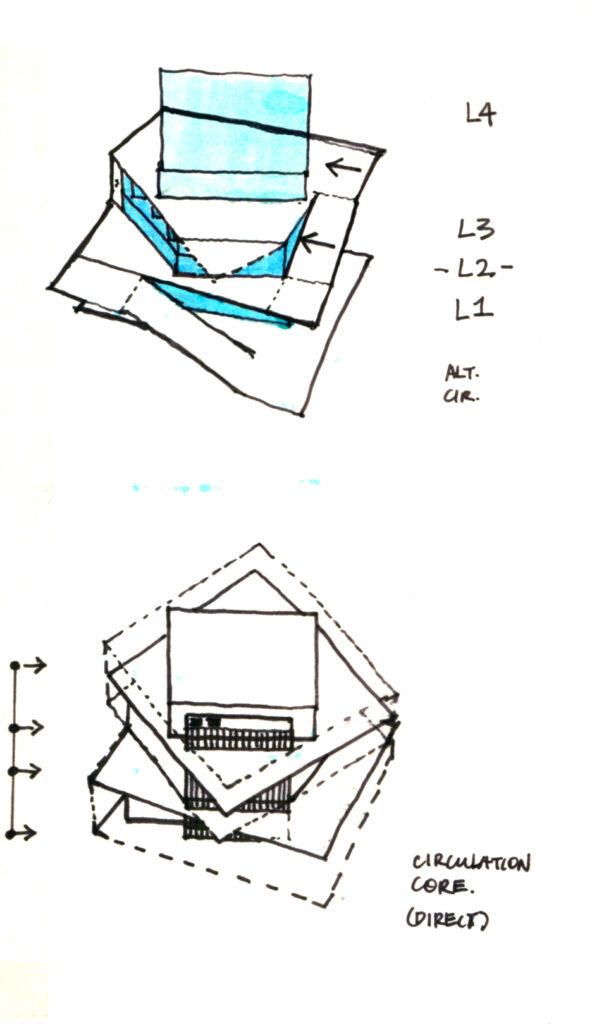

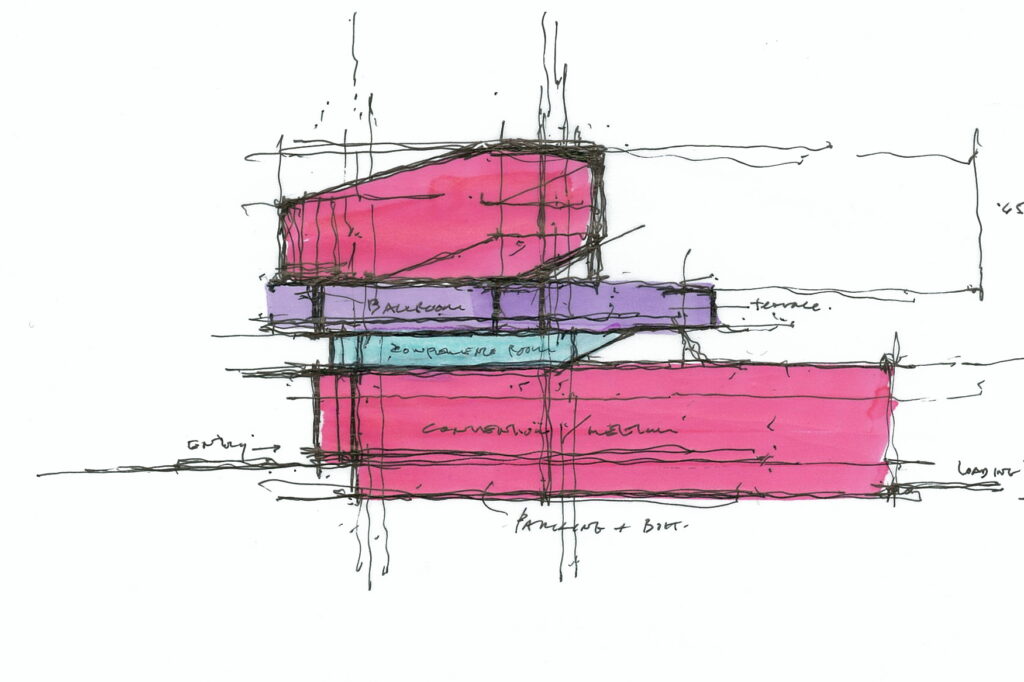

Sketches by Studio Hillier

Akin to her approach at Becton Dickinson, “Barbara did two sketches that were traditional and one that stacked the volumes,” he said. What set the third sketch apart was its rational ability to effectively organize the convention program, the aspirational vision to meaningfully link the project into greater moments of purpose for people, and its respect for the environment.

“The group right away decided to pursue the stacked approach, even increasing the budget to make it so,” Bob said.

Hiller approached the stacked convention volumes through a simple layering. Sculpting and separating the forms created opportunities between and outside the convention volumes to form a series of civic spaces that would extend the functional program as well as link spaces to the surrounding views and skyline. A network of ramps and stairs acts as a thread that links the ground plane upward and through the project, a true rethinking of the urban fabric.

Copper, a cost-effective material at the time, shrouds most of the exterior volumes. Each form is dynamically expressed by the weight of the convention spaces themselves, as well as the shifting interplay with the civic spaces that wind upward along and through the entirety of the project. The extensions expressed through a distortion in form were critical to providing shade and comfort for the civic spaces in the Texas heat and also create the compelling filtered light captured in Leonid’s photos. The perforation within the copper panels, with a gradient of transparency moving from the bottom of the forms upward, adds the final layer that diffuses the direct sun exposure. At night, the copper shroud gives the entire volume a transformative aesthetic, where the skin takes a back seat to the light, showcasing the systems of structure and space within and between.

On a cold December day, by Texas standards, our return to the Irving Convention Center was greeted by a large Christmas bow lining the edge of the lower volume. The LED lighting danced in with the color of a candy cane in the afternoon sun. The building has been well-maintained and respected, albeit in a way one might only expect in North Texas. It is clear the building is loved for its own unique charm.

Most cities look inward when it comes to urbanism. However, the Irving Convention Center was intended to be an active player in defining its neighbors. “You would think this building would have inspired the surrounding environment, but rather it went in the opposite direction,” explains Leonid. “We must question why doing something different was not the direction.”

Photo by Leonid Furmansky

The current condition is a clear indication: an empty plaza surrounded by buildings with their own agendas. Texican Court, to its east, is the most egregious of urban responses with its inward-facing identity and inability to connect to Las Colinas. Aside from the Westin Hotel complex, which relates subtly in form and material to the convention center, our visit to the site prompted questions.

“What is happening around the Irving Convention Center today is noise,” Leonid says, “and you have to wonder what it would look like if the trajectory of design were reversed.”

For a building that has been underwhelmingly documented, we hope the accompanying photographs prompts the “what ifs.” What could have happened differently? What will take shape in the future? After all, both Dallas and Fort Worth are facing similar questions with their future convention centers.

With the recent passing of Barbara Hillier at age 71, we feel even more urgency to not only bring attention to the impact of her work, but also to remind us why a place like the Irving Convention Center should be respected. “Reflecting back, and when I think about moving forward, our focus should be to understand buildings and cities through our unique points of view,” Leonid says. “In a way, our photography and documentation should remind people why design is important, why we should save buildings, as well as remind us of what is good and beautiful.”