Is the Pope Catholic—and Should his Architect Be Too?

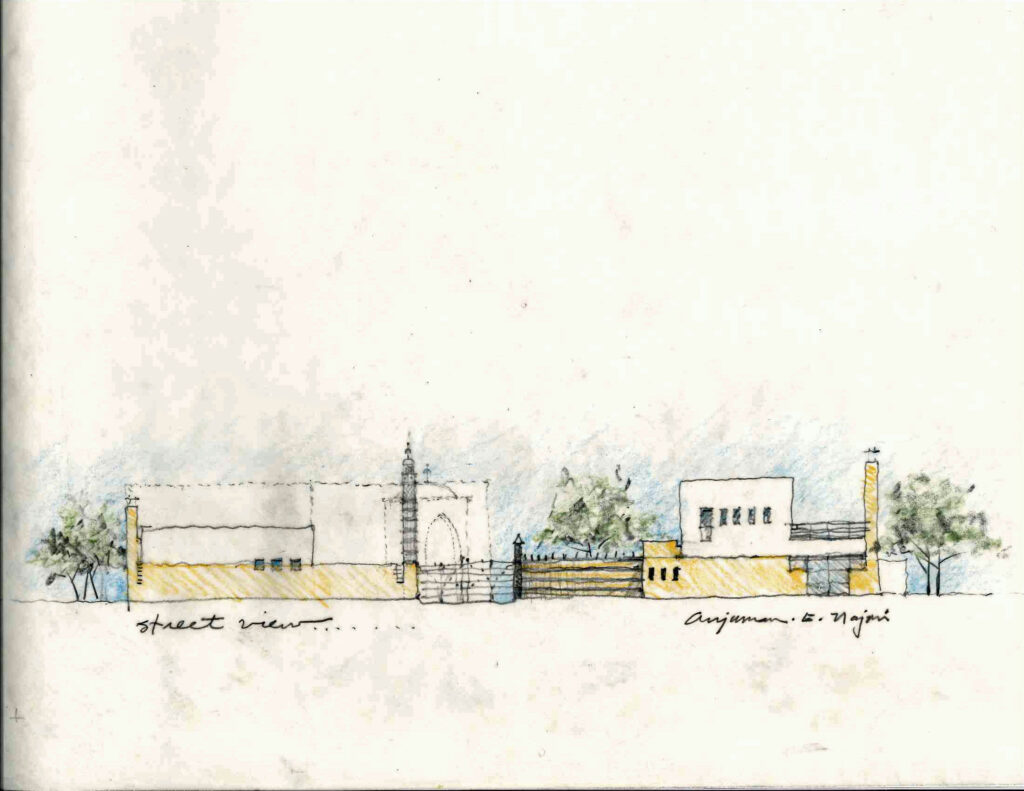

Sketch by Joe McCall, FAIA

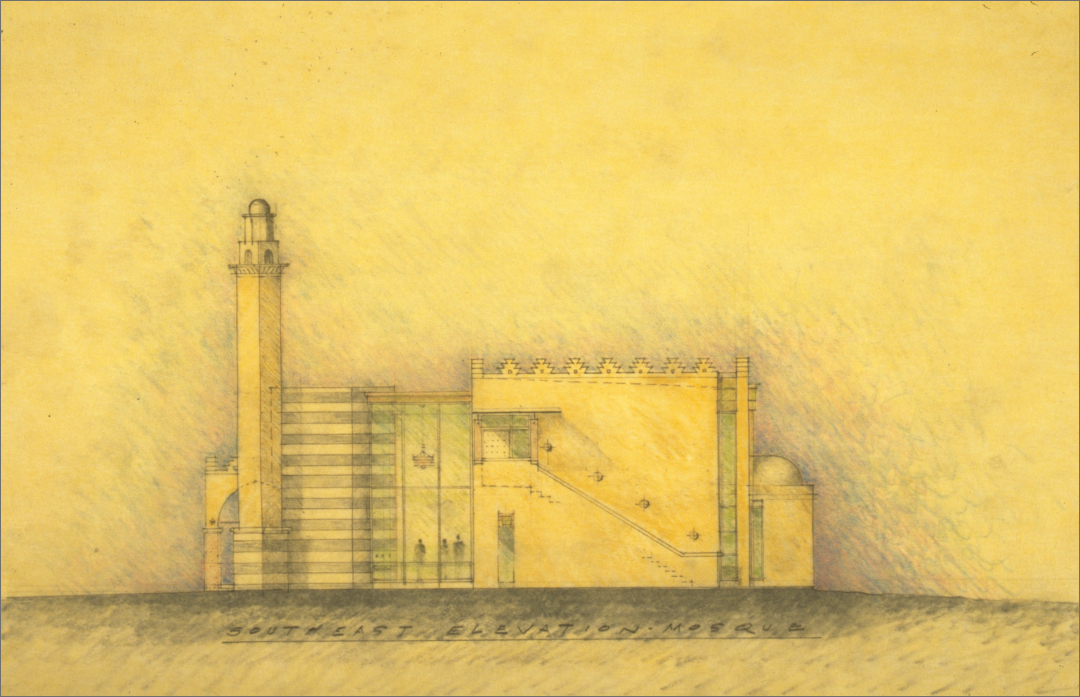

Sketch by Joe McCall, FAIA

Beyond the sardonic, rhetorical question in the headline above lies another honest question: What roles do an architect’s beliefs and piety play in the design and realization of spiritual spaces? Are there ramifications if an architect practices another faith or is even a person of secular beliefs? To dissect the question further, is a Baptist architect at a disadvantage in designing a United Methodist church or a Shiite architect in designing a Sunni-based mosque?

Other than the knowledge and experience of a particular faith — its liturgy, rituals and beliefs — most of us might agree that the true criteria for the creation and realization of a truly spiritual space transcends well beyond the traditional baseline qualification of experience or belief.

We need look no further than revered architects and their seminal works to debunk the question of allegiance or belief in a faith as a precondition of its successful design as a holy or spiritual space.

Le Corbusier was an avowed atheist, but he also had a strong belief in the ability of architecture to create a sacred and spiritual environment. He designed two important religious buildings: the Chapelle of Notre Dame du Haut at Ronchamp (1950-55) and the Convent of Sainte Marie de La Tourette (1953-1960). Le Corbusier wrote later that he was greatly aided in his religious architecture by a Dominican priest, Père Marie-Alain Couturier,who had founded a movement and review of modern religious art. Le Corbusier wrote: “In building this chapel, I wanted to create a place of silence, of peace, of prayer, of interior joy. The feeling of the sacred animated our effort. Some things are sacred, others aren’t, whether they’re religious or not.”

Alvar Aalto, Hon. FAIA, surrounded by Lutherans faithful to the national church of Finland, was not religious, even absenting himself from Christmas services. Despite his lack of religious faith, his ecclesiastical works — particularly his churches and parish centers from the 1950s and 1960s in Finland and abroad — remain some of his most inspiring projects. What distinguishes Aalto’s religious projects from those of many contemporaries, however, is their ambiguous relation to religious tradition and imagery. Just as Aalto remained careful not to associate with any particular political viewpoint, he was careful not to commit to any particular religious doctrine.

Louis Kahn, FAIA, born of Jewish parents, immigrated to the U.S. at age 5. He was married to a Jewish girl, Esther Israeli, by a rabbi, although it was said to be done to pacify his parents. He never celebrated Jewish holidays, but over time he donated to Jewish causes as well as to the Unitarians. He was described as a person of great spiritual depth, although he did not practice any religion himself. While two of his greatest synagogue designs were never built, two of his most successful projects were a church (First Unitarian in Rochester, N.Y.) and a mosque (part of the National Assembly Building of Bangladesh).

Frank Lloyd Wright, a lifelong Unitarian with a minister for a father, is well known for one of his earlier works, Unity Temple in Oak Park, IL (1909), and later for Beth Sholom Synagogue in 1954 and Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church in 1956. Wright had a pantheist reverence for nature. He once stated, “I believe in God, only I spell it Nature.” He also said “ugliness” was his idea of sin. Amen.

Recently, Anastasia Calhoun, Assoc. AIA wrote a fascinating article in Texas Architect on awe — that experience that transcends our understanding of the world — and the neurological basis and measurement for the feelings of oneness and interconnectedness that often arise in association with the experience of awe in contemplative buildings compared to the ordinary. She states, “we are sentient constructs, each bestowed with a wondrous living network of cognitive circuitry, and that we shape, and are shaped by, the world around us. It is in our best interest as designers, but more importantly as human beings, to acknowledge the power of intuition in our work and our lives; to turn off the chatter in our minds; to pause, breathe, and marvel at the beauty that surrounds us.”

We intuitively know and sense this ineffable trait of awe, spirituality, and contemplation. Such senses of awe are not reserved strictly for religious spaces but can be realized in secular spaces in powerful ways as well. Kahn’s Salk Institute, through form, space, light, and even silence, masterfully creates a sacred place. A local example, at a far different scale and program, is the Dallas Police Memorial, designed by Ed Baum, FAIA and codeveloped with our firm, Oglesby Greene Architects. Here no liturgy or ecclesiastical trappings exist — simply a wondrous metaphorical object and place that evokes an emotional, contemplative spiritual setting.

The juxtaposition of materiality and nature are other ways that architects have successfully created spiritual spaces void of religious program. Kahn’s Salk Center, Carlo Scarpa’s Brion Cemetery and Peter Zumthor’s Therme Vals come to mind as calm, contemplative spaces of clarity.

With certain liturgical exceptions (a minaret, Torah, baptistry, etc.), there are few fundamental forms of worship spaces in most major religions. Throughout history, many sacred spaces were switched from one religion to another, depending on those in power. Hagia Sophia in Constantinople morphed from its original Greek Orthodox creation in 537 A.D. (900 years) to Roman Catholic (57 years) to an Ottoman mosque (458 years), and now is a museum. The Pantheon was stripped of its sculptures of pagan gods, which were replaced with Christian imagery while the architecture itself stayed the same.

Other projects have been conceived and realized purely nondenominational or interfaith by design, such as our own Chapel of Thanksgiving by Philip Johnson, FAIA in Thanks-Giving Square. The House of One, by Kuehn Malvezzi architects and currently under construction in Berlin, is billed as the world’s first house of prayer for three religions; it contains a church, a mosque and a synagogue. Eero Saarinen’s MIT Chapel from 1955 began as a shared Christian-Jewish space. Here, from behind sculptor Harry Bertoia’s beautiful shimmering screen, a Torah cabinet rises hydraulically through a trapdoor at the press of a switch to adapt to the occasion, while sharing its inspiring form, materiality and light for both faiths to experience a truly spiritual space. Last year, the Vatican Chapels opened in Venice as a potpourri of 10 chapels by international architects, including Norman Foster, Hon. FAIA and Eduardo Souto de Mourao. It is “not only religious, but also secular as well, as a path for all who wish to rediscover beauty, silence, the interior and the transcendent voice, the human fraternity of being together in the assembly of people and the loneness of the woodland where one can experience the rustle of nature which is like a cosmic temple,” said Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi, president of the Pontifical Council for Culture.

Reflecting upon the architectural selection for a religious project being predicated by the broad-brushed word qualifications, the seminal question is its very definition or interpretation as to prioritizing such criteria for optimal results. So does the pope’s architect need be Catholic, or Christian, or even a believer in God as a prerequisite for consideration, not to mention the candidate having a recent history of designing Catholic churches?

The Brooks Act of 1972 is a U.S. federal law that requires the government to select engineering and architecture firms based upon their competency, qualifications, and experience rather than by price. Today, virtually all municipal, county, and state agencies have adopted a version of this law in the form of a Qualifications Based Selection process, or QBS. They are by law neutral or nondiscriminatory as to race, religion, and gender. Their process involves the solicitation of “requests for qualifications” and subsequent “proposals” from shortlisted firms. Quantitative point systems are assigned to qualification criteria, with extremely heavy weight assigned to not only “experience in similar or specific project type,” but often “in the past five years.” Under such a system, the most points equals the most qualified. A firm with little to no experience in a project type has virtually no mathematical chance to be in the running. The result is a self-perpetuating pool of architectural firms that have such experience separating themselves from those that don’t. Selection committee members or facility staff can be naturally biased as to the safe or conservative selection of a firm with experience and predictability versus gambling with a less familiar, riskier choice.

If such criteria were in place for most of the iconic religious buildings in this article, these architects would not have been selected. The same would be true for Oglesby Greene’s award-winning Islamic mosque project, where we had zero experience and were generally unfamiliar with the nuances of the Muslim faith. While criteria such as experience or history of being within budget, on schedule, sustainable, and diverse in makeup are important, the void — the missing key criteria — is the experience and ability for awe-making. Such measurement is, in fact, measurable, as noted in Calhoun’s article mentioned above, though not quantifiable to the degree of documenting and transcribing into an RFQ or RFP. Nor is the question even asked. Short of documenting neurological laboratory findings, it is for most of us a real but immeasurable and ineffable quality that we sense. Sadly, some decision-makers may simply not sense or undervalue such qualities.

But let’s hope that, as Lou Kahn once said, “One feels the work of another in transcendence-in an aura of commonness and in belief.”

The accompanying case study of the Masjid mosque reveals the inefficiencies, trials and errors, and redesigns encountered in the journey of the project I headed up in our office several years ago. But also realized was an opportunity and curiosity to somewhat naively explore a new arena with eyes wide open for a fresh look at a building type and culture, unencumbered by the accrued postulates of the particular faith.

Case Study- Masjid, Irving, Texas

It seems odd that I, an Anglo-Saxon Protestant Texas architect, designed a mosque, or masjid, for an India-based Muslim community in Irving, Texas. Some mix of fate, circumstances, and Allah’s will — combined with architectural firm credentials and design skills — led to a seemingly incongruous assemblage. This narrative speaks to the interactions, translations, and architectural interpretations interwoven to shape the resulting mosque for this transposed community, bonded by their unique religion and culture.

Over 6 million Muslims reside in the United States, and, among major religions, it is reported to be the fastest-growing. Anjuman-e-Najmi Dallas Inc. is the corporate name for the Dawoodi Bohra Jamaat community of Dallas-Fort Worth. Members, relocating from their native India, represent a Shiite Fatimid (descendants of Mohammed’s daughter Fatima and son-in-law, Ali) denomination of Islam. Their roots trace to the Fatimid period, 969 C.E. to 1140 C.E., a dynasty that ruled over Egypt and North Africa. Their worldwide leader, known as Dai-ul-Mutlaq, is His Holiness Dr. Syedna Mohammed Burhanuddin.

Architectural Selection

The Masjid project did fall, in part, from the heavens, bypassing any committee selection process. A community leader, who continues a family legacy of building and restoring mosques, learned of our firm through a mutual friend and approached us, not so much over credentials but from a social connection. By the end of the second meeting, the project budget and size were established, we agreed on fee, and shook hands. To our client, that was the contract, a handshake. Little did we imagine at the time the bond and resulting friendship that would ensue from this symbolic gesture.

Our firm’s conventional business practices, like most, compelled us to press for a formal contract. Our ignorance and naivety of the Muslim religion quickly exposed itself. Fortunately for us, the client, a successful international businessman, was graceful in dealings with Westerners not of his religion and native culture.

The standard AIA agreement contains interest clauses for unpaid invoice balances after designated periods, which we completed and forwarded for review and signature. He bluntly marked through this section in its entirety, and we learned that his religion does not allow interest payments or income. Despite not having any previous working relationship or even knowledge of the client, we decided to move forward and extended “good faith” without such provisions. Throughout the project, the client proved worthy of such good faith. As the project concluded, we received a significant “bonus” beyond the contractual fee as an act of gratitude. That was a first as well.

The consultant team proved another melting pot. The structural engineer, a close family friend, was dictated by the client and became a wonderful asset. Not only was his engineering excellent, but he also was an invaluable interpreter and arbiter in another context, as he had been raised a Dawoodi Bohra Muslim. We selected the mechanical/electrical engineer, who often worked successfully with us and happened to be Jewish.

Program and Site

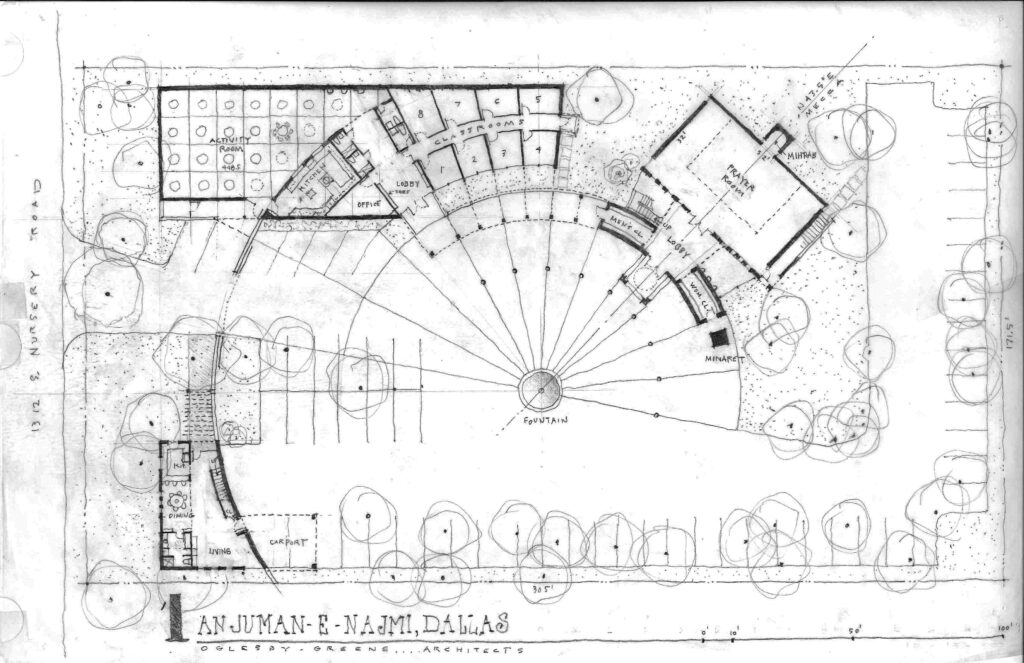

The program consisted of four distinct components for the proposed mosque accommodating about 200 members: a prayer hall (bait-us-salat), a school (madrasa) for religious studies, a dining/community hall (jamat khana), and the priest’s residence (darul-imarat).

Historically, mosques were located geographically based on attendance. Today it is the same, except the religion and community are not concentrated in the U.S., as in Muslim-dominant countries. Dawoodi Bohra members reside over a huge area of cities and suburbs. The client requested a traditional minaret, which serves as a symbolic marker for worship much like a contemporary steeple. But the traditional act of adhan, or the call to prayer five times a day from atop the minaret, would fall on deaf, if not unreceptive ears, within this eclectic neighborhood.

Design Criteria and Influences

As non-Muslims with no experience in such projects, we anxiously sought a primer, a code or a rulebook delineating liturgical and cultural do’s and don’ts. We never found one and instead relied upon our own research and an extremely patient and didactic client. The unorthodox programming and schematic design process involved significant trial and error on our part, combined with the layerings of liturgical requirements from client reviews.

The Dawoodi Bohras wanted certain traditional elements from the Fatimid period to be included within the new facility. Particular reference was made to the finely detailed Al-Hakim and Al-Azhar mosques in Cairo, Egypt. The empowering distinction is the selective recall of symbols and forms to be interwoven into the project versus demand or expectations for a traditional mosque design. Architectural elements included keel arches with their precise formula for construction, geometric-patterned crestings adorning the perimeter walls, parapets and copings, specific form/composition of the minarets and mihrabs (prayer niche centered on the qibla wall), and unique patterning in mosaics, stone and wood carvings.

The paramount design criterion was the qibla, or direction of prayer toward Mecca. From Irving, it calculated to be N43.5E. Considerable clarification and confirmation was requested, including true vs. magnetic north, for the accuracy of prayers being aimed and received. Another requirement was that the floor of the prayer hall be directly on the ground, void of any air space. Also, no construction could be above the mihrab, or niche, axial about the qibla wall. The prayer hall’s plan dimensions were set as a width of 52 feet (52nd Dai-ul-Mutlaq) by 32 feet in depth (reference to the 32nd Dai, who had an important role). The minaret height also was determined to be 52 feet. Groups and bays of five were desired.

Translating Spatial and Symbolic Needs

While never specifically delineated in any programmatic requirements, it became clear that the mosque design had to be, above all, an anchor for the identity of its community. It bonds its users in many ways, through both secular and spiritual needs. Their multicultural day-to-day lives dilute their culture, which the mosque distills and refocuses again.

Budget constraints demanded that richness be reinterpreted into the detail, form and collective composition versus its traditional materiality. Further importance was given to the prayer hall by layering traditional Fatimid elements only on the prayer hall itself, thereby stratifying its significance. A tension between traditional and modern idiom was established to honor authenticity and clarity for each.

The priest’s residence (darul-imarat) sites with frontage to the neighborhood, as does the office and receiving to the public street. Otherwise, the mosque orients inwardly, privately, to itself. The traditional reinterpretation of a central court (sahn) is applied as a public collection space and the physical and spiritual linkage of all four building elements. A fountain is centered in the circular space, symbolic of ablution prior to entering the prayer hall (referencing the Al-Hakim mosque, Cairo). Its entry lies on axis from the fountain’s center toward Mecca.

The dining hall (jamat khana) is developed on a nine-foot module (54 by 45 feet), allowing for groups of eight to nine to sit on floor around a 36-inch round serving platter. Handwashing stations are prominently integrated within the space. It serves as an annex for special occasions when the prayer hall’s capacity is exceeded. Placed between these two primary uses are the seven classrooms (madrasa) for liturgical studies, used mostly on weekends.

The prayer hall (2,600 square feet, excluding the forecourt area) accommodates about 200 worshippers. “Ladies” occupy the peripheral mezzanine area above, while the “gents” align their prayer rugs along the ground floor toward the qibla. The mihrab centers on the qibla wall’s five bays, bearing a Koranic scripture carved and gold-leafed overhead. The scripture translates as, “In the name of Allah, the most gracious, the most merciful.” Flanking the mihrab, two round, carved gold-leafed medallions bear the names of Mohammed and his family members (Ali, Fatima, Hasan and Husein). Upon entry to the forecourt, shelving for shoe storage fills each side along the curving masonry walls, with toilets at ends.

Muslim liturgy and culture created occasional dilemmas for consultants and code authorities. Development codes base parking requirements on a space per linear foot of “pews” for religious facilities. In the absence of pews, we submitted a “prayer rug plan” to determine an official occupancy count, affecting exiting and plumbing fixture requirements as well. Both conventional Western and Eastern-style water closets were utilized, stymying code and accessibility reviewers.

Iftetah

In July 1998, upon the construction’s completion, a celebration, or Iftetah, followed. The community (mumineen) of Dallas offered to their worldwide holy leader (Aqa Maula), His Holiness Dr. Syedna Mohammed Burhananuddin, the facility to be pledged as a masjid. He accepted and ceremoniously “unlocked” its doors. The significance of this event to community members was overwhelming. About 2,000 followers from worldwide arrived for this special day.

To be in the presence of their Aqa Maula is a cherished life goal. The head of the construction company and I were the only non-Muslims invited to attend limited portions of the event. The prayer hall filled early and exceeded its interior capacity fivefold, with as many again viewing by video in the jamat khana annex and others pressing to view through the windows. Everyone was adorned in traditional Dawoodi Bohra dress — the men and boys in their sayas, kurtas and caps (turbans by the Sheikhs), and the women and girls in their embroidered ridas

His Holiness and entourage had arrived earlier from Bombay and were transported within the mosque grounds by horse drawn carriage to the steps of the masjid. I was positioned in the forecourt directly adjacent to the pair of doors to the prayer hall to be ‘unlocked’. The air conditioning was stressed far beyond its design as the midday temperature rose to 105 degrees outside and certainly more inside.

As His Holiness approached the entry, followers’ chants grew more intense as the crowd, both inside and outside lunged forward to participate in this great moment. If the building structure —the mezzanine, in particular — were ever to fail, this would be the ultimate test.

Despite my lack of affiliation, I truly felt the intensity and significance of the occasion. His Holiness carried an unforgettable aura about him. I was later presented before him and given a beautiful shawl, placed around me. He spoke in a language I did not understand, but upon raising my head and making eye contact, he clearly said in English, “This is a most beautiful building.” I wondered if he had in some way blessed me, and felt as if he had.

The celebration continued long after I departed, headed for my car in a remote parking area. Still in my business suit, I looked down to realize I had forgotten my shoes.

Reflections

Afterward, our insecurities about the mosque’s suitability for worship in accordance to the liturgy of Islam were relieved. The design spoke to those who use it, providing an uplifting, spiritual experience. It was anointed as a holy place and an anchor for its community. This mosque, while collectively unifying, in other respects is an odd contrast of traditional and modern idioms, secular and spiritual aspects, and richness and frugality.

During the course of construction, my mother died. Unbeknownst to me, several Dawoodi Bohra Jamaat representatives traveled to attend her memorial service and had “prayed for her soul” the previous night. The more I observed and discussed their religion with our client, the more similar than different their beliefs seem to mine.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2019 “Belief” issue of AIA Dallas Columns magazine.