Lessons On Vacancy

Credit: GFF

Credit: GFF

There have been two times during my 45-year career in architecture that the condition of vacancy has played a leading role. We founded the firm of Good Haas & Fulton in the spring of 1982 and enjoyed four years of growth and success. Then the regional economic crisis of the late 1980s humbled us greatly.

Fulton, Haas, Farrell and Good at their Trammell Crow Center office in 1985.

The boom of our early years in practice, in which our marketing program consisted of answering the telephone, was driven by the easy availability of money for our clients’ real estate projects. The Garn-St. Germain Depository Institutions Act of 1982 deregulated the savings and loan industry by allowing the S&Ls to expand beyond making residential mortgages to loan up to 10 percent of their assets for commercial projects. Our clients received loans to build a number of speculative shopping centers and office buildings that perhaps should never have been built. (How does a midblock, unanchored, two-story neighborhood shopping center sound, for instance?)

The Good Haas & Fulton team in 1985.

In this reckless environment of speculation and overbuilding, the oil industry collapsed first. West Texas Intermediate crude, which had been as high as $100 a barrel in 1980, plunged from $68 to $26 a barrel within a month: April 1986. Houston’s economy had already gone south in 1983; Dallas followed suit in 1986. The oil price crash took down the large local banks down in both cities. The combination of bad oil loans and bad real estate loans brought about the demise of First National, Republic, Mercantile, Allied and Texas Commerce banks, all of them purchased by or merged into larger out-of-state institutions.

‘THE LAST SKYSCRAPER’

In the early 1980s, each of these banks wanted a signature high-rise office tower, and got them. I remember a column that architecture critic David Dillon wrote for The Dallas Morning News in 1988. He reviewed SOM/Richard Keating’s 2200 Ross Tower for Texas Commerce Bank, calling it “probably the last skyscraper that will be built in Dallas in this millennium.” I refused to believe it in light of the spectacular boom we had been enjoying. But he was correct. All of these monuments were now going begging!

Dallas’ office building vacancy rate soared to 30 percent, the highest in the nation. Without laying off a single person at Good Haas & Fulton, our thriving young firm went from 31 people to 14 people by 1990. Talented young professionals had to go elsewhere to advance their careers. And they could move to Washington, D.C., Boston or San Francisco to find a good job because this recession was regional rather than national.

Other fine Dallas architecture firms closed their doors or merged to survive, or they were purchased by firms headquartered elsewhere. AIA Dallas suffered from reduced membership and closed its bookstore by 1988. In 1993, Texas Architect editor Joel Barna chronicled this era of vacancy in an excellent book appropriately titled The See-Through Years: Creation and Destruction in Texas Architecture and Real Estate 1982-1991.

The collapse of the Texas real estate market in the late 1980s ultimately caused the closure of 168 S&Ls and 334 banks by July 1990. In his book, Barna cites the fact that at the bottom of the bust “there was more vacant office space in the towers of Houston than there was total office space in Atlanta and Denver combined.”

The Good Fulton & Farrell office in the Centrum in the early 1990’s.

Our firm emerged from the grip of vacancy by the early 1990s with a new name, Good Fulton & Farrell, and as a smarter, leaner, more humble firm. That period was frightening, but it shaped us into the practice we are today. The City of Dallas, however, experienced lingering impacts from the loss of vitality from vacancy, which leads to the second story.

BOEING BLOW

In 2001, I was serving as the chairman of the Central Dallas Association (now known as Downtown Dallas Inc.). That March, Philip Condit, chairman and CEO of Boeing, announced that the company would move its corporate headquarters out of Seattle to one of three finalist cities: Chicago, Denver, and Dallas. The criteria were represented to be transportation, business climate, education and quality of life. Rather than allow the Greater Dallas Chamber to wine and dine them, the Boeing contingent sneaked into town and did its own touring – like the restaurant critic who prefers to dine anonymously to avoid getting special service.

Chicago was selected. Legend has it that Condit’s wife was the lead decision-maker. She was looking for a rich urban experience and laid Dallas’ failure to impress directly at the feet its lifeless downtown streets. Storefronts were empty. Other than Neiman Marcus, retail had abandoned downtown. Office workers moved from parking garage to workplace in the below-grade tunnel system. Our Arts District was an idea that had yet to achieve any critical mass, so cultural offerings appeared to be lacking. Only the four loveliest of our empty historic office buildings had been converted to residential or hotel use by that time – not enough to make a difference in street life. In a word, vacancy ruled the day in downtown and the headlines weren’t good.

“Boeing fight was lost downtown/Firm found Chicago more vibrant” – The Dallas Morning News, June 1, 2001

“Downtown’s awful truth/Is downtown Dallas the worst central business district in America?” – Dallas Business Journal, March 16, 2001

“Dallas is the only CBD in the nation expected to lose property value by 2003” – Integra Realty Resources

“Dallas’ downtown office vacancy rate leads the nation” – Urban Land Institute

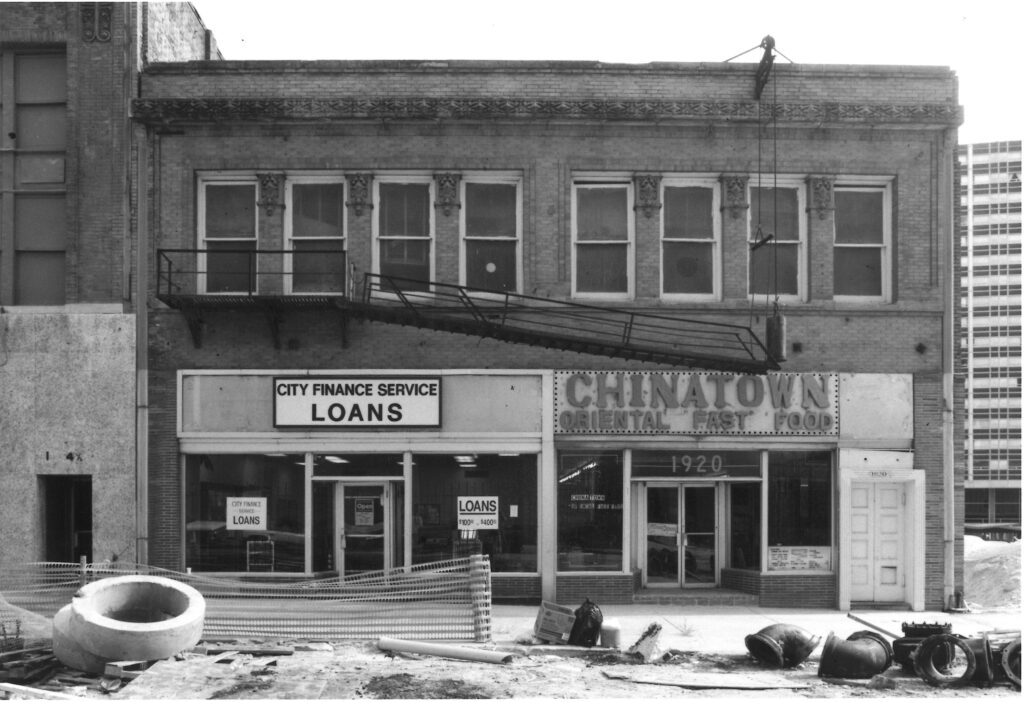

Blighted storefronts on Main Street in the 1990’s.

BACK ON OUR FEET

But sometimes a snub like Dallas received from Boeing can inspire a successful self-improvement program. The Boeing decision had a profound impact on the resolve of our leadership to improve the vitality of downtown. Mayor Ron Kirk immediately called to order the Mayor’s Task Force on Downtown. Laura Miller, Hon. TxA followed that initiative when she became mayor with her Inside the Loop Committee. That group, led by Belo chairman Robert Decherd, was to come up with the agenda for the most pressing items for advancing the health of the center city.

Of the items identified in that 2002-2005 post-Boeing decision period, virtually all have been accomplished.

- Build a convention center hotel.

- Design and complete three downtown parks.

- Extend the McKinney Avenue trolley into downtown.

- Advocate for the second DART alignment through downtown.

- Advance the quality of our pedestrian linkages.

The 2006 bond program was heavily weighted toward investments in downtown projects and assets. So in this case, as in the case with our architectural firm, the pains inflicted by vacancy led to lessons learned and the inspiration to improve and rise above.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2018 “Vacancy” issue of AIA Dallas Columns magazine.