Light Beyond Boundaries

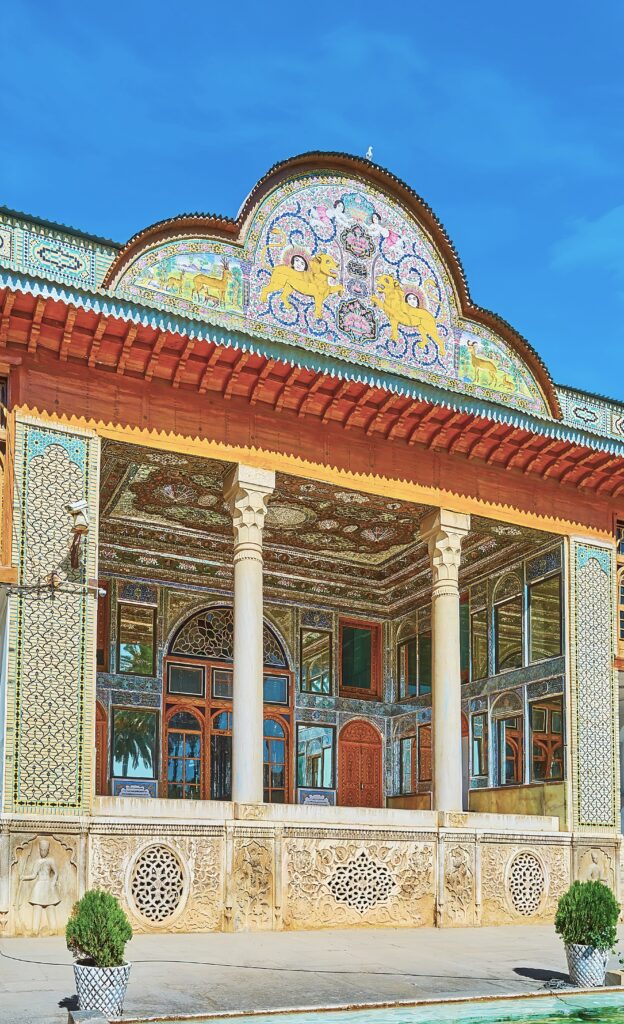

Narenjestan Qavam House, (1879–1886), Shiraz, Iran. Photo by Evgeniy Fesenko

Narenjestan Qavam House, (1879–1886), Shiraz, Iran. Photo by Evgeniy Fesenko

Architects have always sought ways to bring light into space, guiding it vertically through ceilings, horizontally through windows, and across openings to create brighter, more livable environments. Persian architects went a step further: they sought to capture it, multiply it, and set it into motion. By covering the walls and ceilings with countless geometric pieces of mirror, they created radiant surfaces where light danced endlessly within the interior, inviting occupants to experience light, reflection, and shadow.

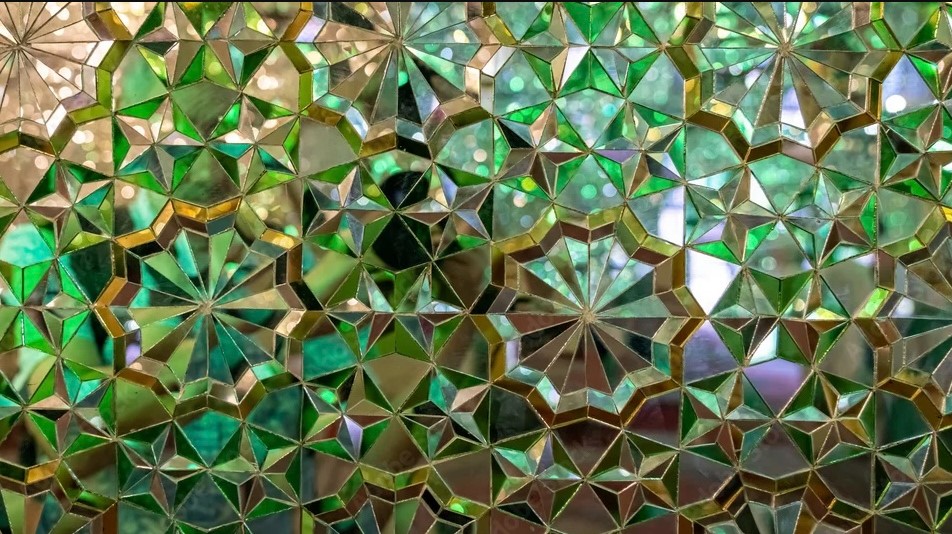

These techniques are known as Ayeneh-kari (eye-neh-kah-ree), also called Iranian mirror artwork. Many believe that Iranian mirror work was influenced by Italian, especially Venetian, glass-making traditions. During the Safavid era (1501–1736), large European mirrors were imported to Iran, but many of them broke during transportation. Instead of discarding the pieces, Iranian artisans began reusing the fragments in creative ways. That’s how ayeneh-kari was born, turning a problem into a beautiful new form of design. In this craft, thousands of small, precisely cut mirrors are applied to walls, ceilings, and domes, creating surfaces that sparkle with movement. As sunlight or candlelight enters a space, it is fractured, scattered, and multiplied across every angle, turning architecture into a luminous, ever-changing environment.

Ayeneh-kari demanded extraordinary craftsmanship. Artisans cut glass into countless tiny triangles and other precise shapes, then carefully set them into gypsum plaster to form intricate, star-like mosaics. These mirrored fragments were often combined with tilework, stucco, and stained glass, producing layered compositions that balanced geometry with ornament. The smallest fragment contributes to the overall harmony, turning walls and ceilings into canvases alive with light, color, and pattern.

This use of mirrors was not simply decorative; it was intentional. Depending on the space and desired atmosphere, Persian architects thoughtfully varied the application of mirrorwork in both interior and exterior settings. On balconies and veranda walls, mirror mosaics were arranged to capture reflections of the surrounding garden, projecting trees, sky, and sunlight directly onto the architectural surface. As the day unfolded and the seasons shifted, these reflections transformed, turning the wall into a living canvas of light and nature in motion. A striking example can be found in Narenjestan Qavam in Shiraz (c. 1879–1886), where balcony mirrorwork reflects the courtyard garden into the space, blurring the boundaries between architecture and nature through the movement of reflected light.

Within interiors, mirrorwork carried even deeper symbolic meaning. In mosques and shrines, it created spaces of spiritual intensity: fragments of light scattered across domes and walls evoked stars in the heavens, surrounding worshippers in a sense of divine presence. The Shah Cherāgh Mosque in Shiraz, originally founded in the 12th century and extensively restored during the Safavid era, is one of the most extraordinary examples. Here, countless mirror fragments, combined with stained glass, transform light into a brilliant kaleidoscope. In palaces, mirrors adorned reception halls and ceremonial chambers, multiplying candlelight into dazzling displays that elevated the grandeur of royal power. And even within private homes, such as the House of Zināt-ol-Molūk, built in the late 19th century, mirrorwork was paired with colored glass and painted tilework to animate domestic interiors.

Photos by Tanya Hendel

Photos by Saba Banan

The reflection of light takes a different contemporary form in the United States. In Texas, a distinct relationship with reflection emerged, especially during the late 1970s and 1980s, when Dallas experienced a wave of glass skyscraper construction. Many of these buildings were clad in highly reflective façades that acted almost like urban mirrors. Towers such as I.M. Pei’s Fountain Place, the Bank of America Tower, and the Hyatt Regency at Reunion Tower captured and reflected the city, sky, and shifting sunlight across their surfaces. This reflectivity served two purposes: practically, it reduced heat gain in the intense Texas sun, improving interior comfort and energy efficiency; visually, it softens, blurs, or even partially disappears the buildings into the skyline. The city center reflects back to its inhabitants, creating a sense of openness and an expansive horizon and dissolving the boundaries of the city into the sky.

Today, this fascination with reflection continues at a much more intimate scale. The ÖÖD House, founded in 2016 by Jaak and Andreas Tiik and originally developed in Estonia, now has cabins here in Texas. These prefabricated modular structures are built with mirrored façades that allow the structures to “disappear” into the landscape, reflecting trees, sky, and horizon in a way that creates a sense of quiet immersion rather than monumental presence. The mirrored exterior blends the cabin seamlessly into its surroundings, extending the natural panorama and visually erasing the building so that nature appears continuous.

Design Meets Nature: ÖÖD Mirror Houses Debut at Austin, by Lake Bastrop

May 12, 2025

“ÖÖD is excited to announce the opening of its newest location in the US: two award-winning ÖÖD Mirror Houses nestled within the peaceful landscape of Lake Bastrop, just 45 minutes from downtown Austin.

Each of the two signature ÖÖD Mirror Houses is carefully positioned to reflect the surrounding forest, seamlessly blending modern luxury with immersive natural beauty. The 180-degree mirror walls create a striking yet subtle presence, allowing the architecture to blend into the trees while guests enjoy a luxurious private retreat with uninterrupted views of nature from three sides.”

While both Iranian mirrorwork and Texas’s mirrored architecture use reflection to shape perception of a space, they do so with different intentions and at different scales. In both traditions, there is a desire to capture the surrounding environment, whether the garden, the city, or the sky, and to let these reflections soften the boundary between built form and nature. However, the continuity of reflection unfolds differently. In Iran, mirrorwork extends from outside to inside: reflections of trees, sky, and daylight are carried inward, where fragments of light animate walls and ceilings, creating intimate, contemplative, and often spiritual interiors where space seems to expand from within. The experience becomes embodied, light surrounds you, and you feel held inside it. In Texas, reflection is oriented outward. Expansive glass façades mirror the skyline and horizon, dissolving a building’s mass into its surroundings and allowing architecture to blend back into the landscape. Here, reflection softens the exterior presence of the building rather than intensifying interior light. It is an architecture that deflects attention to itself, instead giving precedence to its surroundings, allowing the natural landscape becomes the focus.

By shaping reflection, shadow, and movement, we can create spaces that are alive, continuing a tradition where architecture does more than shelter life; it illuminates it.