Max Levy, FAIA

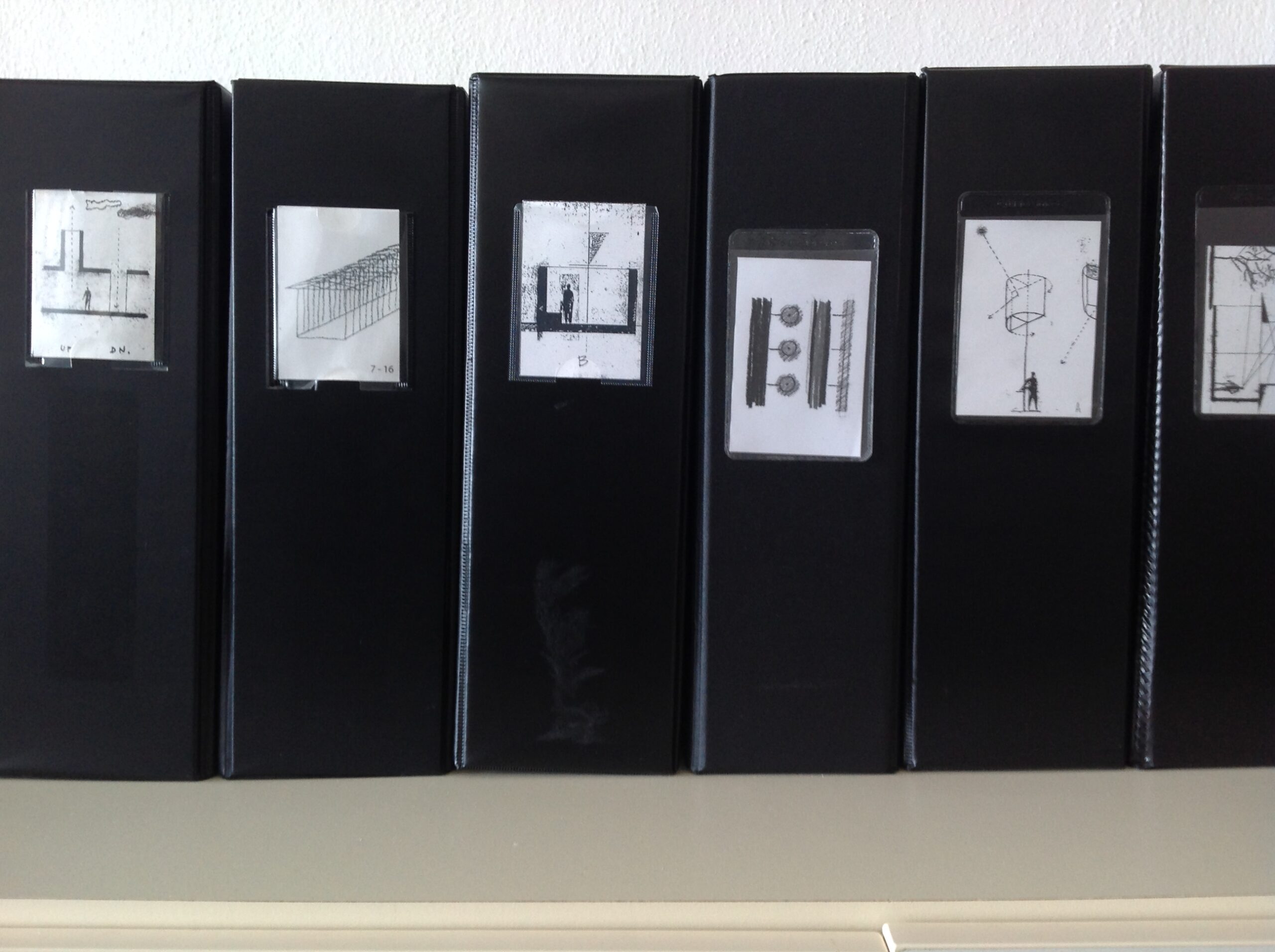

Max Levy, a Fort Worth native, studied at Berkeley and USC before practicing at SOM in Chicago. He then returned to his home state to work at the Oglesby Group before beginning his own practice in 1984. His highly decorated portfolio champions Texas regionalism while bringing awareness to nature and the sense of wonder design can evoke. His creative skill has led to a library of carefully archived sketchbooks, basswood models, and collection of written articles.

Nicolas McWhirter, AIA and Madalyn Melton sat down with Max to discuss performance in architecture.

What has performance meant to you in practice?

There are two types of performance. One dealing with pragmatics and one dealing with poetics. You can’t successfully bring poetics into architecture unless you deal forthrightly with all the pragmatics.

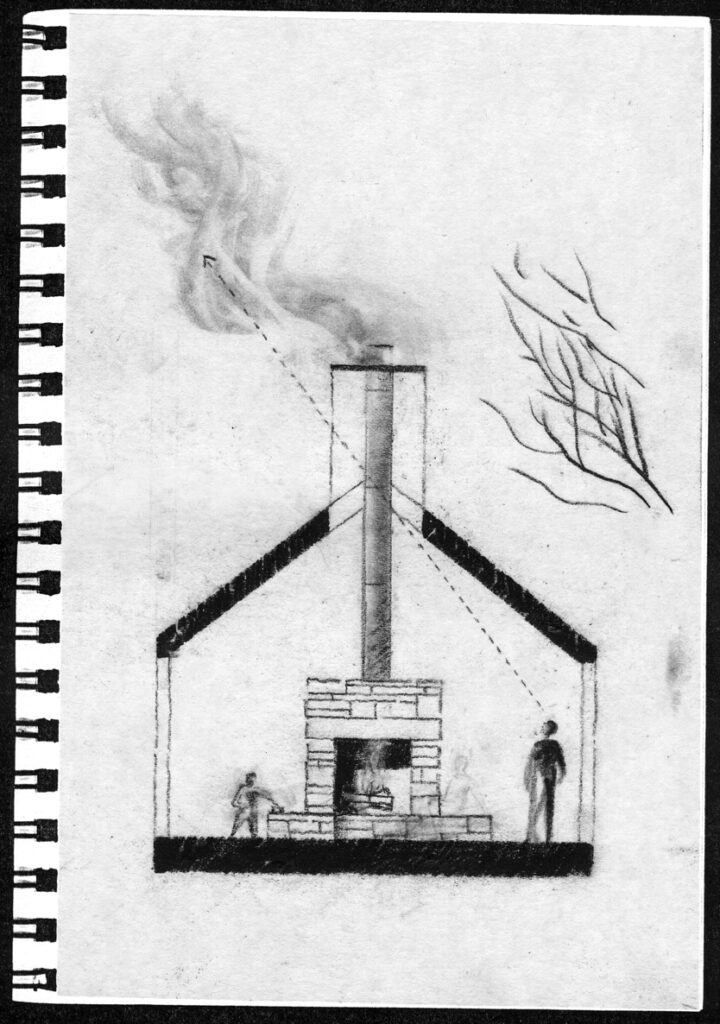

If poetics are meaningfully woven into the life of a building, people will care about that building and therefore take care of it in ways that allow it to endure for a long time. When programs and technology change, buildings that over-concentrate on metrics empty out, stand idle, and all too soon get demolished. If the greenest thing we can do is not tear down buildings, maybe the poetic buildings are actually greener.

Your approach and body of work is a perfect case study because there’s simplicity in it. How do you introduce poetics while balancing budget?

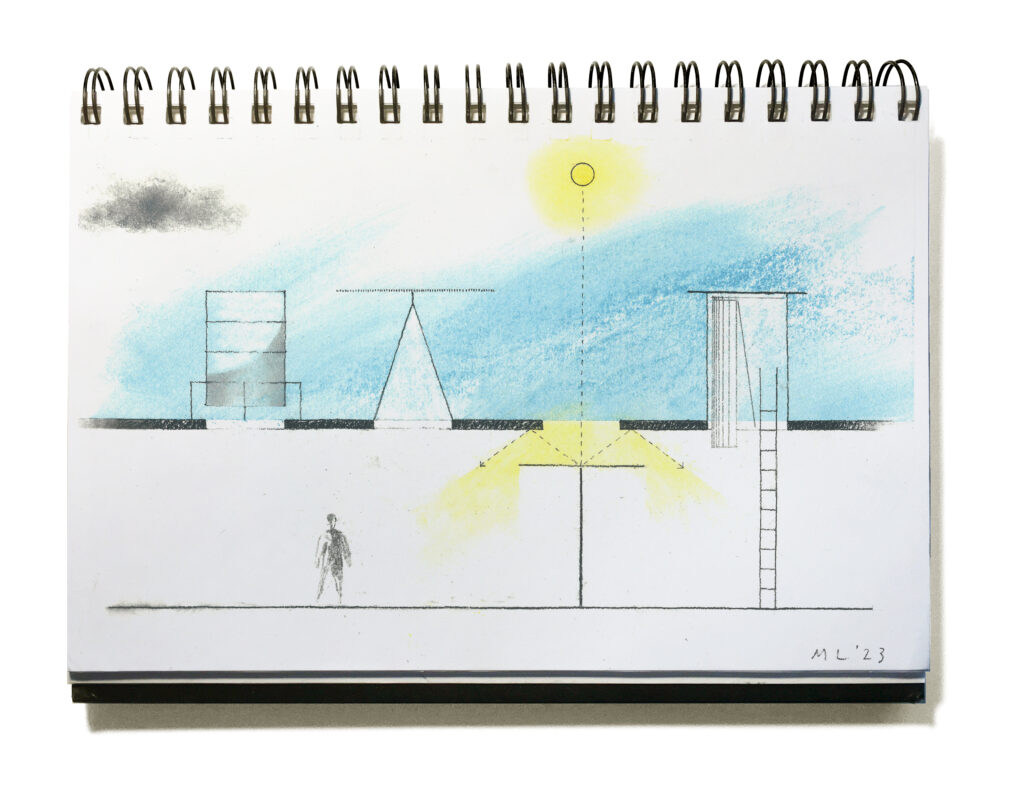

For architectural poetics to work you must attend to placement, proportions, alignment, and editing. These things may require more of the architect’s time, but they are basically free construction-wise. They clarify what you’re trying to express by clearing away the background noise. If you get things lined up and pay attention to proportions, there is something divine.

What holds up your day-to-day practice behind the scenes?

My days are usually 90% dealing with life’s complications, about 9% dealing with design, and 1% architectural daydreaming. Design’s what I’m always trying to get at of course, but all the complications keep getting in the way. Unfortunately, you can’t always rely on design activity to relieve that frustration because design is an unrelenting cycle of elation and despair. So, the 1% daydreaming is crucial to give you a lift and help you keep going. Although the complications take you away from design, they also give you the opportunity to come back to design. This helps you see your work more clearly and makes it better.

The public may not understand what we do and see architects with a sense of mystery. How have you shown clients the depth of architecture and that we have flexibility in design?

Clients rarely ask for a creative adventure. But I’ve found that if you accommodate all their programmatic concerns, and then go on to weave something imaginative into their project beyond program, they become enthusiastic. A kind of spark appears in the project and in them too. In fact, if in further developing this imaginative design concept you discover that you really can’t pull it off, and you break this disappointing news to the client, they will often hold your feet to the fire and insist you work harder to make it happen somehow. In this sense clients sometimes help you keep the faith.

In your recent “Grace Notes“ article in Texas Architect magazine you talked about bringing elements into a project that go beyond the program. How do you maintain focus on these ideals?

Have you ever had a client afraid to tell you they didn’t like something?

Yeah, or tell me too late. More often than that, however, are clients who are embarrassed to reveal that they don’t really understand drawings. The only antidote to that is to make the presentation itself a beautifully crafted thing apart from the design of the building. Then the client will usually interpolate that the beauty of the presentation is going to wind up in their building, even though they may not fully understand the specifics of the drawings. So, it’s important to “design” your presentation and to “design” the words that accompany it so as to express the architecture to come. How much time and effort you put into the script matters.

You’ve spoken on an awareness, but not a fear of AI Factor in our practice. Can you explain further?

Computer generated graphics or designs, though remarkable, usually have an airless quality about them. Meanwhile, the human touch, whether of the mind or the hand, carries with it something from beneath our consciousness, some instinct or yearning breaking through. A bit of this elusive realm seems to want to be involved with the making of architecture. And when this shows up in a design concept, or in a hand drawn sketch, or a lovingly made physical model, it seems to awaken a client. Their spirit and the underlying spirit of the project connect. This gives the architect more running room to bring depth and meaning to a project beyond merely a thin veneer of attractiveness or stylishness.

What advice would you have for young people in architecture that want to hang on to elusive effects in architecture while we’ve gone almost entirely digital?

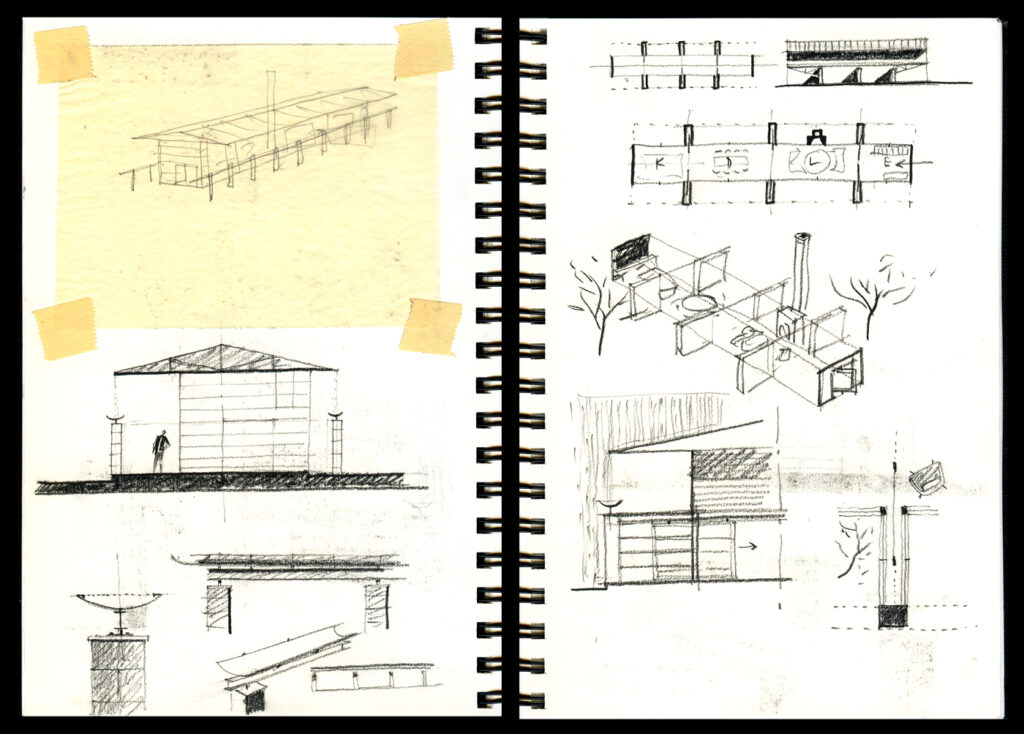

The computer is essential today, but it distances buildings from feeling. To avoid this shortcoming always begin a design by hand. And before designing, trust the power of architectural thoughts that come to you unattached to an actual project. You may think you’ll remember these fleeting thoughts, but you won’t unless you capture them and put them on paper. The crudest little diagram will do. In fact, these mysterious doodles are usually better than your more self-conscious belabored drawings. Such thoughts don’t show up on demand, so you must always be ready with your butterfly net. These thoughts will be incomplete, but don’t try to work them out too soon or the spirit of the thing will vanish. Let the idealism of the sketched thought ferment for a while. Then when a real project eventually comes along that has an affinity for that thought, you can bring it into the project and develop it, not as a cut-and-paste thing, but as something foundational.

What is root of those things, is it always emotional or is it sometimes technical?

The emotional aspect is the end, and technicalities are means to get there. If I were to pull up one of my sketchbooks, you’d see stuff that appeals to the mind, or the eye, or the heart. The trick is to take any one of those things and combine the other elements. The goal is to practice being sensitive to intuition.

We don’t know much about the metaphysical realm, only that it exists, it’s powerful, and there’s certainty hovering around it. Everything seems so uncertain in life these days, but there’s a reassuring sense of certainty in intuition. That’s what makes us human.

Did we not talk about anything that you wanted to with performance?

When my son was seven years old, he wanted to come up to the office to learn what his daddy did. He played with my electrical eraser, twirled around in my desk chair, and checked out my drawings, models, and books. At the end of our time, he said, ‘Dad, architecture is about everything!’ He’s right.