Seen Versus Unseen

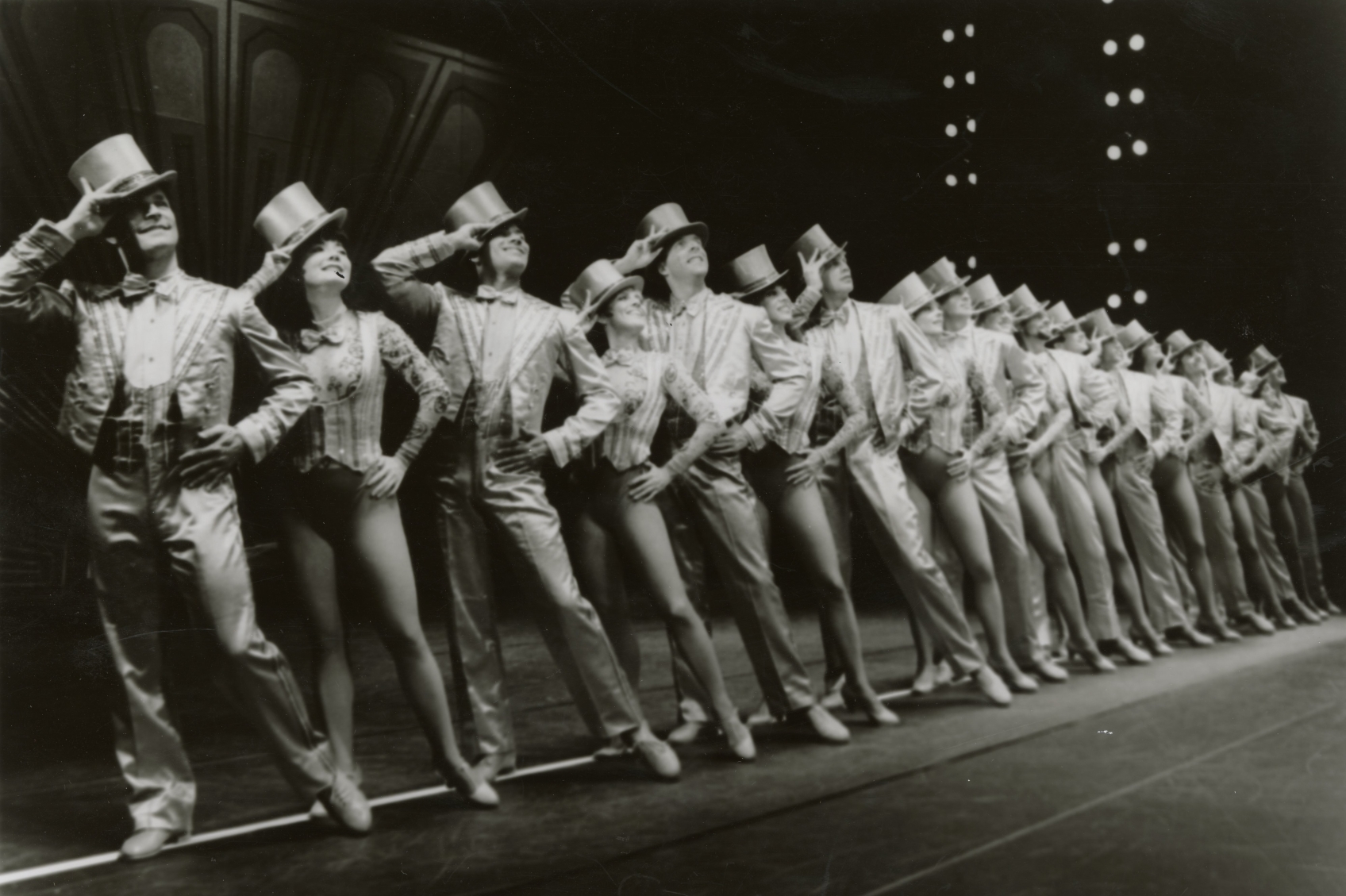

A Chorus Line, 1981. The Bushnell Center for the Performing Arts

A Chorus Line, 1981. The Bushnell Center for the Performing Arts

The audience is shuffling into the theater on a warm Saturday evening. There’s a buzz around the lobby as everyone is excited to see a production making its debut in Dallas – and are maybe a bit excited for the air conditioning. After grabbing a drink and making a final stop at the restroom, theatergoers file into the auditorium to take their seats. The beautiful interior is expertly illuminated. An announcement comes over the speakers reminding everyone to silence their phones.

Then the transformation of the space begins.

The architectural lighting goes down, shrouding the space in darkness. The anticipation builds. Then the stage lighting comes up, and the performance begins. Actors move around the stage, interact with each other and the set, and entertain the audience with clever turns in dialogue. As the applause fades after the last curtain call, the stage lighting fades, and the auditorium is once again illuminated to provide a beautiful backdrop as the audience exits.

The conversations between patrons heading to the parking garage likely focus on the performers, the music, the script, maybe even the set design. Let’s be honest: It may include commiseration on the comfort of the seats and whether the temperature was too hot or chilly.

Less prevalent will be discussions about the lighting. Yet lighting is one of the most critical components to a performance.

In a literal sense, you can’t see what’s happening on stage without lighting. At a deeper level, the stage lighting influences how audience members feel in any given scene just as much as the emotions emanating from the actors. For the entire performance, the stage lighting adds to the action, growing brighter or dimmer to match the mood, and even changing color to emphasize the action.

A good lighting design does more than blast the stage with light or wash the set with color. It can also draw the audience’s focus toward the action that the director wants to emphasize and, critically, away from what the director wants to obscure. The balance between what is seen and unseen is one component of the magic of live theater. There is no on-screen and off-screen as with television and film to show audience members exactly what the director wants them to see.

With live theater, audiences can look wherever they want at any time. Clever set design, limited off-stage space, scenic elements that rise or descend into view, and lighting are the only tools that directors have to keep the audience focused and pull them into the action.

Lighting is also a tool that can have an indelible effect on architecture. When done well, lighting enhances the architecture, deepens textures and layers, and invites people in by directing them toward entrances and other features. When done poorly, the architecture suffers, feels flat, and fails to create a welcoming space. One could argue the difference between good lighting design and poor lighting design is a balance between what is seen and what is unseen.

An excellent yet simple example of this is the board-formed concrete walls surrounding Dallas’ own Moody Performance Hall. Up-lighting and down-lighting the texture of the walls illuminates the proud peaks and ridges while obscuring the valleys. The result is the transformation of the cold, hard concrete into a velvety texture that softens the room and creates depth in what in reality is a relatively shallow space. But front lighting these same walls would wash out the texture and give the appearance of, well, raw concrete.

This method is all about angles – the angle of the light to the material, the angles of the material’s texture, and the angle at which someone views the material. Most architects recognize and appreciate the straightforward, commonly used approach of wall washing. We can go deeper, though, to draw out hidden or unique elements of the architecture and focus attention in a more intentional and alluring way.

Stanley McCandless was one of the most important influences on modern stage lighting. A Yale drama professor who literally wrote the book on 20th century stage lighting, McCandless developed a design approach that relied on multiple angles of lighting to highlight the facial features and bodies of the performers.

In its most direct application, two primary lighting sources are set at opposing angles (ideally 45 degrees) off center from the performer or the set element being lit. One of these primary sources is a cool color, such as blue. The other is warm and contrasting, like amber. The combination of angle, intensity, and color creates a sculpting effect for everyone and everything being lit, with dramatic yet pleasing shadows. Secondary filler and back lighting can gently light other elements that will appear to recede into the background and add depth to the overall diorama.

While there is much more nuance to the McCandless method, these are the basic elements. The method has proved so effective that it is still taught and often used today to light productions from high school up to Broadway. Just like with architectural lighting, this method has had to adapt to the transition to LED sources. But the impact remains the same: McCandless developed a lighting approach that is timeless, dramatic, and beautiful. Imagine whole buildings – the set design and backdrops of our real lives – being lit to such great effect.

Yet whole buildings don’t always need to be lit. There is an intrigue and drama to be found in selectively lighting facades or, more to point, selectively not lighting building elements. This is part and parcel to the magic of live theater – quite literally in the Broadway and West End productions of Harry Potter and the Cursed Child.

The world of witches and wizards is brought to life through a wide variety of special effects, some more complex than others. One of the simpler effects occurs during a wand fight between Harry and his nemesis Draco Malfoy. As they fire spells at each other, they each seem to fly through the air as their bodies react to the impact of the spells. This is accomplished with a crew of performers lifting and spinning the lead actors in a highly choreographed dance of sorts. The crew is dressed in black and set against a black background. The lighting illuminates the actors’ costumes and simple set pieces, drawing the focus to them rather than the ninja crew doing the heavy lifting. While children certainly delight in the effect, adults can appreciate how deftly it is pulled off when everything is in sync.

‘Harry Potter And The Cursed Child’ Makes Its Magic The Old-Fashioned Way’

DECEMBER 29, 2019 – 7:54 AM ET

HEARD ON WEEKEND EDITION SUNDAY

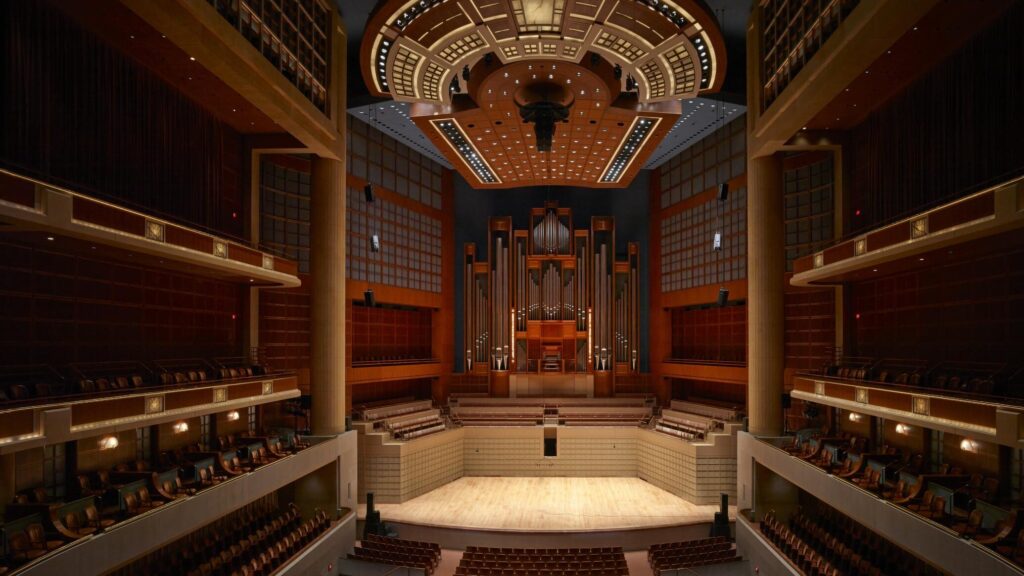

So, too, can architecture seem to take flight or levitate in space. Think of the overhead ceiling reflector at the McDermott Concert Hall at the Myerson Symphony Center and how the warm and richly lit surface sits in contrast to the dark, veiled cap to the room beyond. The contrast keeps the focus on the reflector rather than all the rigging, lighting, and audiovisual infrastructure above. (It’s worth noting that the antithesis of this approach is across the street at Moody Performance Hall, where the technical infrastructure is exposed and lit to celebrate what is often hidden in theaters.)

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

This same concept can be applied to facades, juxtaposing illuminated elements against unlit ones to create depth, focus attention, and even draw people into the building. The NBC Tower along the Magnificent Mile in Chicago is a good example of using selective lighting. At night, the light emphasizes the striking verticality of the building and draws the eye toward the entrance. In doing so, it adds a delicate layer to what, by day, appears to be a hulking structure.

A related move is changing the lighting so that the building or performance can be experienced in several ways, capturing a moment in time and controlling a view that is exciting and mesmerizing.

The dance Caught, choreographed and originally performed in 1982 by David Parsons, utilizes quick strobes of light synchronized with the choreography to give the appearance that the dancer is flying. With each flash of the light, the audience sees the dancer seemingly hovering in space. Unlike in Harry Potter and Cursed Child, the dancer is propelled off the floor by his own feet. It is the absence of illumination when those feet are on the ground followed by the sudden burst of light when the dancer is in the air that creates the stunning effect.

While strobing is generally not recommended for architectural lighting, it can be adapted in many ways. Different parts of the building could be lit at different times, using a variety of lighting angles and color (like McCandless did) to change the mood and experience. It’s akin to creating the different scenes of a performance that affect how the audience interprets the action on stage. Nobody wants to see a show that has static lighting throughout, and what is a building but one big stage on which all of us live our lives?

Stage lighting is all about contrast – drama versus subtlety, intensity versus calm, seen versus unseen. Choosing what to light and, perhaps more important, what not to light can have as big an effect on a design as do the materials that are selected or the organization of the elevations. Architects and architectural lighting designers can learn a lot from stage lighting design on bringing out the inherent drama in a building.

If more architects learned what makes great stage lighting so powerful, they would elevate their designs. When taken to the next level, the integration of the lighting design from the start of the design process would lead to innovative solutions that inform the architecture rather than lighting design that is merely reactive. There is so much nuance – so much drama! – that could translate from stage to street to create stunning, memorable, and award-worthy lighting designs.