Beyond the Border: (Un)Rooted

Nature for culture. Nature for society. Nature for nature. Its essence omnipresent and definition untethered to any one meaning: natural, urban, prehistoric, designed, wild, manicured, curated, preserved, restored. Its variability and permanence make it magical—taking on memory, emotion, and infrastructure. Our relationship to it, also variable, evokes feelings of freedom and healing or devastating consequences at its most poetic.

I believe that how we value nature and design with it will chart a course for either energetic growth or outmoded stagnation of city culture. Can a different development philosophy—one that prioritizes positive social-ecological dynamics—help us build a connected and tangible here? Because I am here, and because this is where I want to be, how I can advocate for a here that values people, nature, and culture equally and authentically?

By exploring the nature x culture nexus through the duality of two Texas cities—the one where I grew up and the one where I live now—the similarities and differences, the good and uncomfortable, and the variation of nature’s role in culture and urban development are revealed.

South Texas—Rooted in Land

Southern Texan-Mexican border towns are some of the most unique places in their geography and culture. Living along the border enables an understanding of how Earth’s natural shape, manifested through hydrology, is a mechanism to create geopolitical boundaries that cannot contain culture in the same way it attempts to contain people. Growing up, the “boundaries” of community did not halt at invisible county lines, nor did they halt at the very visible riparian condition that separates two countries. The feelings of community, visibility, and culture permeate—we are connected with or without permission. Simultaneously we see that same portal of connection being manipulated as a boundary of separation, a barrier, and at times, a graveyard… What if nature had a voice? Would she approve?

Walking over the Rio Grande River doesn’t feel disjointed or like you’re arriving in another country—it feels like an extension of the community where we grew up. Because of this, I didn’t understand the significance and deep rootedness of [RGV border] culture until I no longer lived in the place I grew up. I’m no longer there—a city located within the larger geographic collective known as The Rio Grande Valley. This collective feels representative of my identity, extending past myself and into a larger people, region, and community. Hunters, farmers, ranchers, vaqueros—the RGV roots and maintains a big piece of our character in our relationship with the land. Though undoubtedly tied to the economy, the majority of people are not using the land to make themselves rich; they’re using it to connect. There’s a respect, a reverence, and an appreciation for what it can provide for you, how it can sustain you, and the opportunity it provides to gather with friends and family. This is how nature serves as a conduit for culture—one that bridges people on either side of the Rio Grande and acts as an infrastructural tether to connect us as neighbors and people.

Though these values centered around our natural environment didn’t come full circle to create a “sustainable urban plan” for our cities in the RGV—for example, we are still heavily vehicle-dependent and seemingly allergic to density—they did contribute to a cultural foundation that translates into auras of familiarity. Its result is an inexplicable one, one that immediately connects people that have never met before in places across the country and around the world. “Oh you’re from the valley?! No way! I grew up in ___” … the feelings of home flood back, making me now more grounded, more here, than I was moments ago. This ease of connection had set up a host of cultural expectations and standards within me without my realizing, only presenting themselves when I left and arrived somewhere else.

North Texas—Rooted in Development

Now, after my migration north, I’ve realized that self-reflection carves out a path to assimilation and comfort, which is not always easy when you no longer live in a community that is culturally familiar. To non-native residents of a big city and an even bigger metroplex, it’s easy to feel disconnected, isolated, and hesitant to explore outside of your neighborhood—which often involves getting on a highway and driving 20-40 minutes in any which direction to arrive at your destination. Here, the river also contextualizes experience, but its impact feels opposite. It shocked me that cultural and urban differences can feel more distinct crossing a river within a city than crossing a river to another country. Earth’s natural shape is still being manipulated, but this time for efficiency and the promise of economic benefit that has yet to come to fruition. With Big Business serving as due north, it’s no wonder fleeting feelings of connection pass through as we drive around the city, similar to the river that’s been stripped of its curves, relocated, and channelized to maximize efficiency—flowing, flowing, gone. Intrinsic respect for land cannot exist as a cultural value when others prioritize development and profit over people and planet. As Ned Fritz said during a 1983 interview to defeat the Trinity River Project 50 years ago that saved the Great Trinity Forest, “The environment is up against entrenched profit-making interest as well as long-standing cultural myths, and so to save the environment requires great cunning, skill, breadth of appeal, and, therefore, diversity. So I’m in favor of everybody joining the environmental movement or participating in it as much or little as they see fit … From that respect, why, we need the hard-liners. We need real cutting edges.” About 50 years later, have we drawn these lines? Have we created these cutting edges to diverge from business as usual? Or did Ned’s message get lost in the entropy of capitalism? There seems to be a veneer on the “new” that pops up because feelings of inauthenticity are unequivocally tied to requirements of capitalism—how can you feel rooted here if here doesn’t feel authentic?

Where interventions of greenspace could serve as a cultural thread, stitching up the urban fabric of a disjointed metro, we’re seeing nature being sacrificed for vehicular infrastructure to get people places faster. And for what? Does driving a car bring you more peace than walking down a tree-lined street, or relaxing at the park, or biking through the city? Highways leave thoroughfares of cultural fragmentation all over the metroplex all the while public greenspace exists to serve as a vehicle for human connection. But for some reason, we’re still talking about investing in highway expansion instead of highway burial. We’re divesting from what could be a functional, safe public transit system that not only saves emissions but saves space—space that can protect, restore, and invest in the public green and natural ecosystems within the city. Accessible spaces to gather and unwind among trees and neighbors are few and far between here—not to mention inequitably distributed—so why don’t we do something different?

Fairchild Aerial Surveys, Inc.

Nature Futures Framework – A Different Way

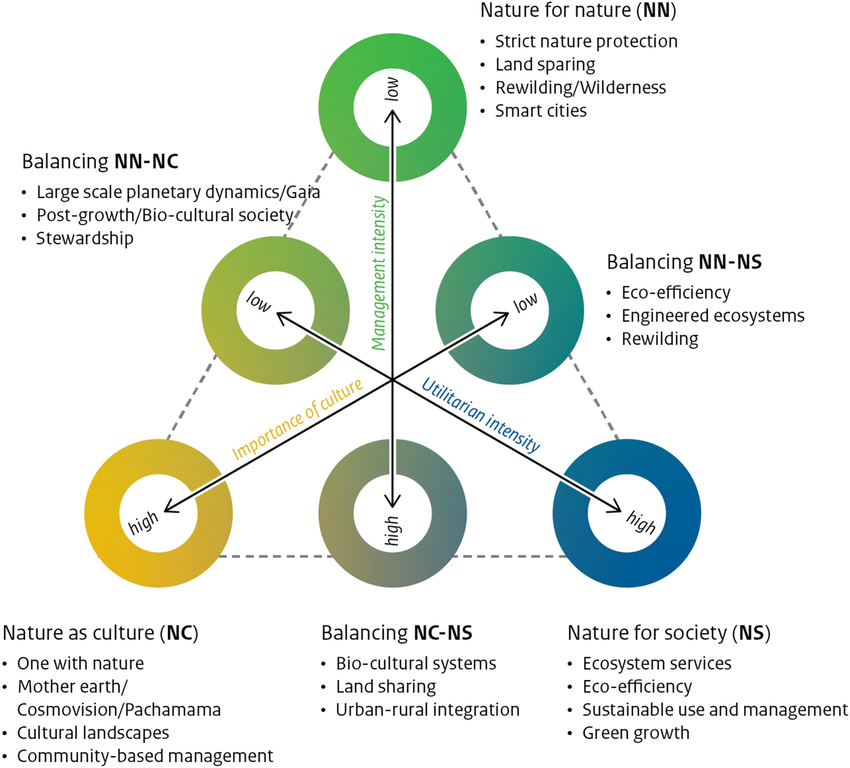

Addressing the negative side effects of the disconnection of humans from the environment, which has been caused by the planning, design, and construction of our built environment, is not a problem easy to solve, but it’s also not outside of our reach. What can we do to stitch back these connections and create positive feedback loops within our social-ecological relationships? How do we make sure we always consider nature when we’re dreaming up a masterplan, writing design guidelines, or putting pen to paper on a site? The Nature Futures Framework provides an opportunity and a vocabulary to do just that. It’s a pluralistic and participatory framework that enables exploration and creation of positive nature futures that depend on how the user group values nature. By going through an exercise that explores stakeholder’s connections and value systems for the benefits of nature, you can uncover how best to preserve, restore, and build with nature to create a symbiotic relationship that is managed uniquely based on project scope. Here we explore and ask, “Do we value nature for nature, nature for society, or nature for culture”?

Bringing the Nature Futures Framework to life: creating a set of illustrative narratives of nature futures

A. Paz Durán, Jan J. Kuiper, Ana Paula Dutra Aguiar, [..] Laura Pereira

“To halt further destruction of the biosphere, most people and societies around the globe need to transform their relationships with nature. The internationally agreed vision under the Convention of Biological Diversity-Living in harmony with nature-is that “By 2050, biodiversity is valued, conserved, restored and wisely used, maintaining ecosystem services, sustaining a healthy planet and delivering benefits essential for all people” READ MORE >>

In the nature for nature perspective, people view nature as having intrinsic value, and value is placed on the diversity of species, habitats, ecosystems, and processes that form the natural world, and on nature’s ability to function autonomously. The nature for society perspective highlights the utilitarian benefits and instrumental values that nature provides to people and societies. The nature as culture/one with nature perspective primarily highlights relational values of nature, where societies, cultures, traditions, and faiths are intertwined with nature in shaping diverse biocultural landscapes.

Having grown up somewhere that operates closer to the intersection of nature for society and nature as culture, it’s a stark contrast now living somewhere that seems to culturally exist somewhere between nature for society and whatever it means to be outside of this triangle. Disconnected. We need a development compass that points us to opportunities that prioritize a different set of values—values that promote the restoration and healing of our ecologies, values that respect land above profit, and values that ensure equitable access to nature and sustenance. These are our rights. If we can acknowledge how an unsustainable growth economy forces us to conform to development standards that don’t prioritize human or planetary health, we can recognize the entropic nature of capitalism we’re continuing to invest in. Radically refusing this path as a collective opens a window into a cultural reset that transforms entropy into momentum. With momentum, our advocacy creates impact. We can advocate for something different. We can design in a way that prioritizes positive social-ecological dynamics, values culture and authenticity, and helps us build a connected and tangible here, together.