Road to Disinvestment

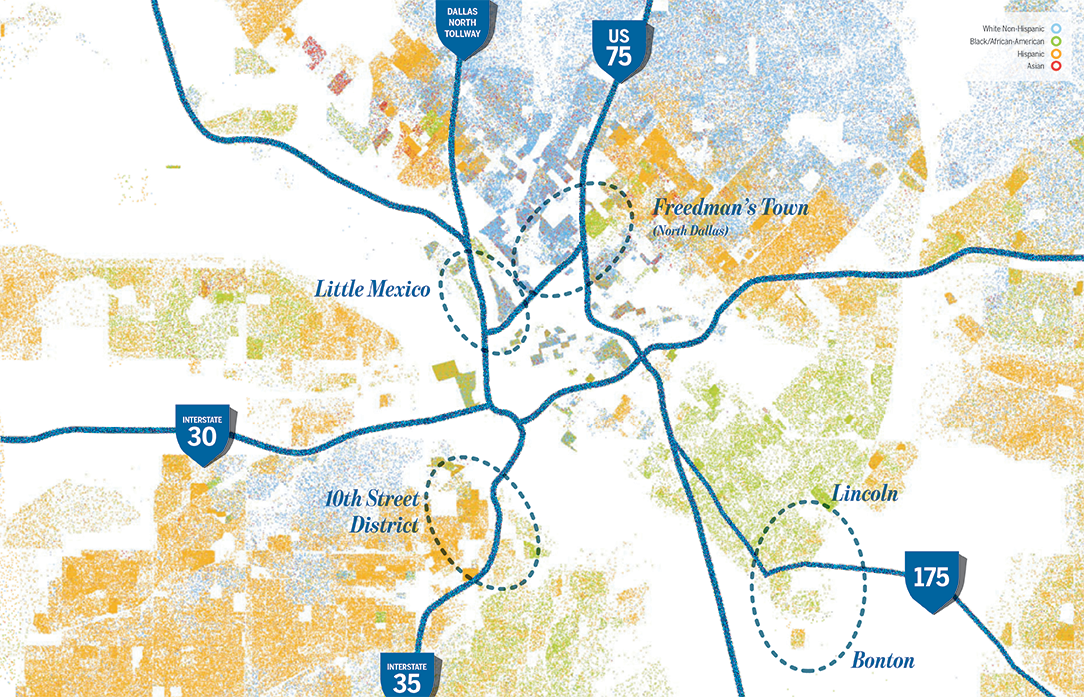

As the Dallas highway system grew, it cut through and destabilized historically African-American and Latino neighborhoods. Those physical barriers continue to divide the city by race today. (Original map copyright, 2013, Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service, Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia (Dustin Cable, creator); additions by Jenny Thomason, AIA)

As the Dallas highway system grew, it cut through and destabilized historically African-American and Latino neighborhoods. Those physical barriers continue to divide the city by race today. (Original map copyright, 2013, Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service, Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia (Dustin Cable, creator); additions by Jenny Thomason, AIA)

A couple of years ago, some of my architecture students at the University of Texas at Arlington (UTA) participated in the Tenth Street Sweep, a survey of the Tenth Street National Register Historic District organized by Activating Vacancy, a buildingcommunityWORKSHOP project. Their job was to catalog vacant houses, missing curbs, broken sidewalks, illegal dumping, boarded-up windows—every symptom of neglect and decay they could find. As we talked together in class, their concern and confusion was palpable: How did the neighborhood get this way?

Tenth Street is one of Dallas’ oldest neighborhoods, and it is deeply important to the history of African-American culture and life in the city. It is one of the city’s Freedman’s towns, established after the Civil War when freed slaves founded their own neighborhoods. The nucleus of the Tenth Street neighborhood formed in the 1880s and 1890s south of the floodplains of the Trinity River and on the eastern side of Oak Cliff—a place where the black community could actually own property during Reconstruction and its aftermath. Across generations, the neighborhood grew and nurtured business leaders, artists, and families.

But back to that original question. What happened to the neighborhood?

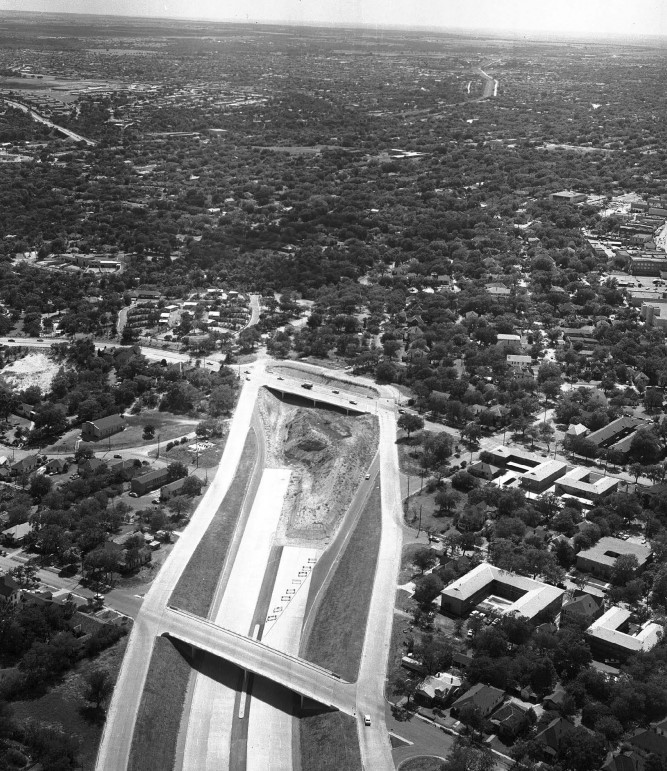

That’s a complicated question and one key chapter in the story is the construction of R.L. Thornton Freeway directly through the middle of the neighborhood in the early 1950s. The highway construction did several things. First, it demolished thriving businesses, undercutting its economic heart. Second, it cut Oak Cliff in half, destroying homes and separating neighbors from each other, disrupting the social networks that make neighborhoods thrive. Third, those who lost businesses and homes scattered to new neighborhoods, further destabilizing the community.

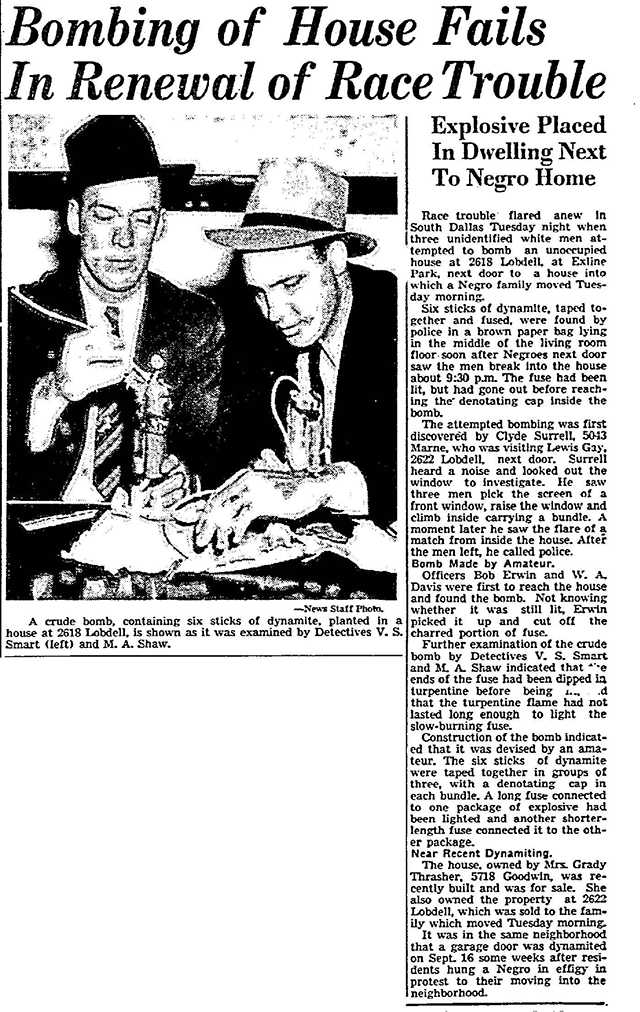

In an era in Dallas history with a huge shortage of housing for African-Americans who were unwelcome in white neighborhoods, these forced moves magnified the detrimental effects of segregation and mid-century racism. As the city’s black population grew and homes were lost to freeway construction in the 1940s, a series of bombings targeted black families that moved to traditionally white neighborhoods. In 1950 and 1951, at least 12 new bombings again targeted the homes of black families in South Dallas who had moved into formerly white blocks. No one was killed and no one was ever convicted for the crimes. These bombings sowed fear and amplified mistrust, leaving African-Americans with extremely limited choices about where they could safely live in the city. All of these actions together created a massive disinvestment in Tenth Street that went, and remains, un-redressed.

Tenth Street is only one of many Dallas neighborhoods eviscerated by highway and infrastructure construction in the 1950s and 1960s. The Freedman’s town of North Dallas—of which only St. Paul United Methodist Church, Moorland YMCA/Dallas Black Dance, and remnants of Booker T. Washington High School remain today—was bulldozed during the construction of Central Expressway in the 1940s, Woodall Rodgers Freeway beginning in the 1960s, and I-345 in the 1970s. The construction of the southern portions of Central Expressway and C.F. Hawn Freeway bisected Lincoln Manor and Bonton, leaving the neighborhoods, which had been contiguous, connected only by Bexar Street. Hundreds of families lost homes and businesses and churches closed. Listings in the 1956 edition of the Negro Traveler’s Green Book for Dallas businesses hospitable to traveling African-Americans show clusters of properties that were all in the shadows of this urban surgery: the Howard, Lewis, and Powell Hotels; the Palm Café; and the Shalimar Restaurant all disappeared.

TO BURY A CEMETERY

The construction of Central Expressway also buried the historic Freedman’s Cemetery beneath its concrete in the 1940s. It was rediscovered 50 years later amidst anguished public controversy over a plan to expand the expressway in the 1990s. After an archeological survey documented more than 1,000 unmarked graves, the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDoT) altered its plans for the expansion. The Freedman’s Cemetery Memorial, dedicated on Juneteenth in 1999, became a powerful reminder of that forgotten past. Standing at its gates, surrounded by the rush of freeway noise, is a potent reminder of the destruction that highways brought to African-American history and neighborhoods.

To the west of downtown in the early 1940s, the expansion of Turney Avenue into the Northwest Highway Connection began a decades-long process of demolition in Little Mexico. Local and state funding turned what had been a neighborhood commercial strip into a four-lane highway with a median connecting Dallas to Denton. Although terms like “civic beautification” flew around the project, Little Mexico’s dilapidated housing was the real target. Rather than investing in the paved streets and water and sewer infrastructure that Little Mexico needed, redevelopment like the highway connection, soon renamed Harry Hines Boulevard, focused on wiping the slate clean and starting over. By the middle of the 1960s, the Dallas North Tollway bulldozed through Little Mexico’s center, repeating the patterns that destroyed businesses and dislocated families and extended social networks.

INTENTIONAL DEMOLITION

One of the issues that is difficult for contemporary observers to grapple with is how intentional these demolitions in African American and Hispanic neighborhoods were. It is critical to understand that they were indeed intentionally targeted for demolition, both through racist national policies established by agencies like the National Highway Administration and discriminatory state and local policies that targeted the poorest and most disenfranchised populations. Highway development proceeded in parallel with housing policies created by the Federal Housing Administration to undermine the economic viability of minority neighborhoods.

Discussions of urban blight and “undesirable” populations may have partially sanitized the language of the planning process, but in the eras of Jim Crow and the postwar civil rights movements, these huge infrastructure projects played a key role in creating and enforcing an urban geography that privileged the priorities of civic elites at the expense of minority populations. This was the case not only in Dallas, but in cities across the country that used federally and state funded highway construction to enact local policies of discriminatory urban renewal.

These stories should matter to us today because they helped create the foundation of the city that we live in together. The city is not a level playing field. Constellations of federal, state, and local policy targeted minority and low-income neighborhoods for disinvestment for decades and the consequences of those choices and policies remain with us today. While the modern highway and interstate system was undeniably a vehicle for economic expansion, it spread the advantages of that expansion unevenly. The historian Raymond Mohl has called attention to the “devastating human and social consequences of urban expressway construction” because of its lopsided impact on the communities of color it displaced and the white middle-class suburban populations it served.

Acknowledging and understanding that our shared urban history contains both utopian optimism and structural inequality is a necessary first step in considering how to move forward.

The issues raised here are far too complex to sum up in 1,000 words and I would hope, above all, that everyone in Dallas takes the time to grapple with them in a serious way. As a historian, I am all too aware of the desire for quick conclusions, easy reads, and sound bites. Our lives are busy, complicated, and full, and history takes time and effort to unravel and unfold. If this essay encourages us to do anything, I hope it is to reflect on, to read about, and to visit places and neighborhoods that are outside of our daily routines and engage more fully in the shared story of the city we all call home.

FOR MORE ON DALLAS NEIGHBORHOODS AND FEDERAL HIGHWAY POLICY

Marsha Prior and Robert V. Kemper, “From Freedman’s Town to Uptown: Community Transformation and Gentrification in Dallas, Texas” Urban Anthropology and Studies of Cultural Systems and World Economic Development 34, No. 2/3, (Summer-Fall, 2005), 177-216.

Hardy Heck Moore, “Tenth Street Historic District,” National Register nomination form, 1994.

Sol Villasana, Dallas’s Little Mexico. Arcadia Publishing, 2011.

W. Marvin Dulaney, “Whatever Happened to the Civil Rights Movement in Dallas?” in John Dittmer, ed., Essays on the American Civil Rights Movement. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1993.

Robert B. Fairbanks, The War on Slums in the Southwest: Public Housing and Slum Clearance in Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico, 1935-1965. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2014.

Mark Rose and Raymond Mohl, Interstate: Highway Politics and Policy Since 1939. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2012.

William H. Wilson, Hamilton Park: A Planned Black Community in Dallas. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2017 “Equity” issue of AIA Dallas Columns magazine.