ACTION!

The slate claps down and as the camera scrolls, background actors chat quietly off camera, actors not in this scene observe keenly from the side, and the lead actors put on a display of what they’ve been rehearsing for months. A quintessential, if not cliché, scene we can all conjure when imagining a film set. Yet, as architects, we would not conjure a similar image when imagining an architectural design studio. However, intriguing similarities emerged during detailed observations of multiple long running design-build studios at the University of Kansas. The parallels materialized as I watched a group of nascent student designers move from the studio, to the workshop, and, finally, to the construction site to assemble something full-scale and tangible in the real world.

HANDS-ON STUDIO EDUCATION

Although hands-on (design-build) approaches to architectural education in the form of full-scale construction continue to develop at schools across the country, as a whole, they resist theorizing. One of the first hands-on studios in the United States emerged at Yale in 1967. The progressive architect and educator Charles W. Moore was the head of the architecture department and founded the First-Year Building Project in collaboration with faculty member Kent Bloomer. The studio offered first-year professional degree students the opportunity to design and build a structure as a collaborative group. Hands-on studios began more regularly staking their ground in American architecture programs in the 1990s with studios at University of Washington (Steve Badanes), University of Kansas (Dan Rockhill), and Auburn University’s Rural Studio, guided by the late Samuel Mockbee. In fact, many directors of hands-on studios can be traced back to some connection to Samuel Mockbee and the Rural Studio. Now, if an architecture school doesn’t offer a hands-on designing and building experience they are seen as old hat. These studios design and construct real life, full-scale projects, using real materials for a real client.

The term “design-build” is slightly misleading. The intent of design-build studios in architectural education isn’t to review the popular alternative delivery method but as a hands-on experience to expose students to the embodied values of real structures, materials, and architectural details.

Design-build studios encourage students to resolve the disconnected nature of drawings to the reality of gravity and material limitations. They teach students that design thinking and philosophy is in the details. The students will draw, work as collaborative teams, resolve conflicts, manage a construction budget, and experience communicating with clients. You may ask yourself, “Can’t these topics be taught in a typical design studio?” They can and should be integrated into studio to ensure that students value these topics. However, the continued growth of design-build studios in architecture education is based in opposition of the design studio’s long running focus on the lone architectural genius developing elaborate representations of grand designs. This concentration on one kind of architect results in the success of a stereotypical architect personality type at the disservice to the naturally occurring diversity of personality and talents necessary for a successful architecture firm.

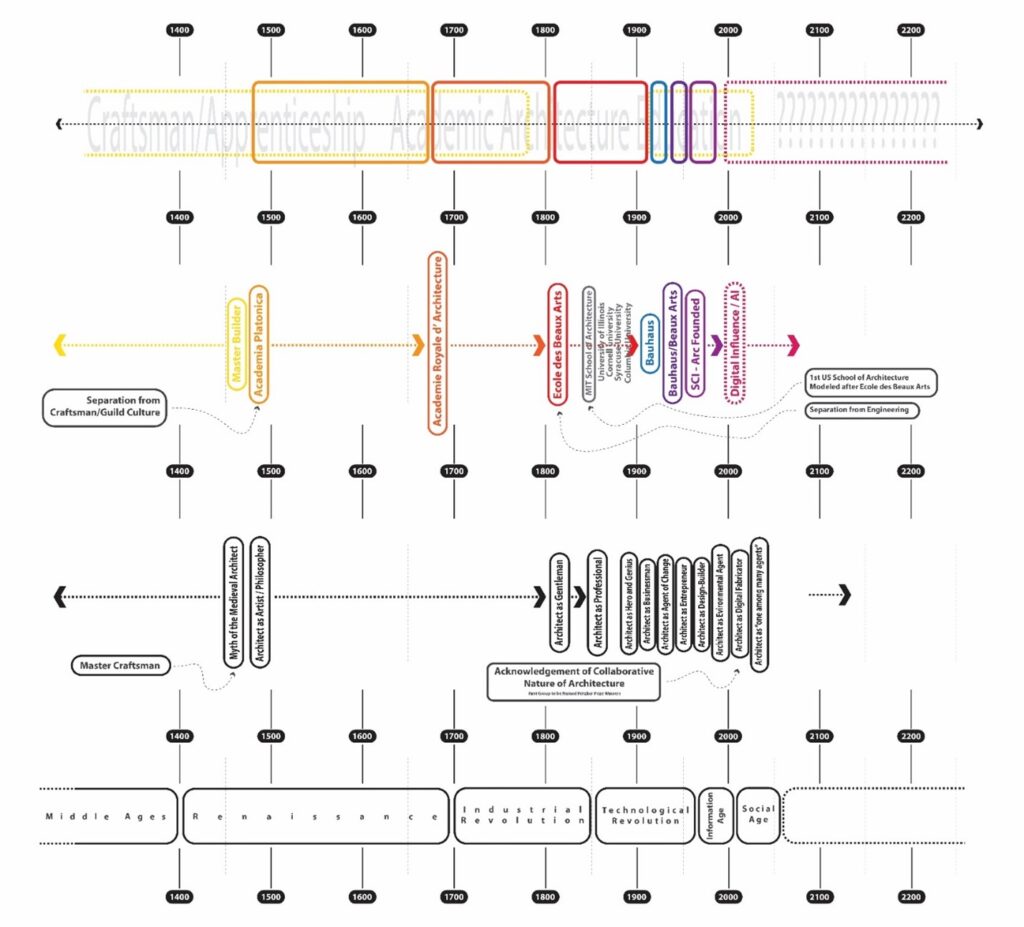

THE SHIFTING AND DIVERSIFYING “ROLE OF THE ARCHITECT” THROUGHOUT HISTORY

The architect’s role in society (or the “Image of the Architect”) and their responsibilities has long been confused with the role of the builder, going as far back as what Dana Cuff refers to as the “Myth of Medieval Master Craftsman”. This was the predominant “Image” from ancient Egypt until the late 15th Century. When the Renaissance established the first Academies of Art and Architecture, the role of the architect shifted to one of an artist or philosopher. This was the dominating view for the next three to four hundred years, until the Industrial Revolution ushered in the Ecole Des Beaux Arts and the persona shifted to the “Architect as Gentleman”. The Industrial Revolution gave way to the Technological Revolution and lead to the formation of the first United States schools of architecture which Americanized the role as the “Architect as Professional”, legitimizing its brand by associating it with doctors and lawyers.

The rapid social shifts of the Technological Revolution led to a shift and expansion to the image of the architect: “Architect as Hero/Genius”, “Architect as Businessman”, “Architect as Agent of Change”, “Architect as Entrepreneur”, “Architect as Design-Builder”. The Information Age and Social Age brought new roles including the “Architect as Environmental Agent” and “Architect as Digital Fabricator”. The architect isn’t a singular agent but an Architect as “one among many agents.” However, at the same time the role of the architect was rapidly diversifying, research at the University of Kanas in the early 1980’s showed that studios were weeding out diverse personality types, focusing more on developing the INTJ (Introverted, Intuitive, Thinking, and Judging traits) at the expense of other more collaborative and social personality types.

THE INDIVIDUAL AND VISUAL FOCUS IN THE DESIGN STUDIO

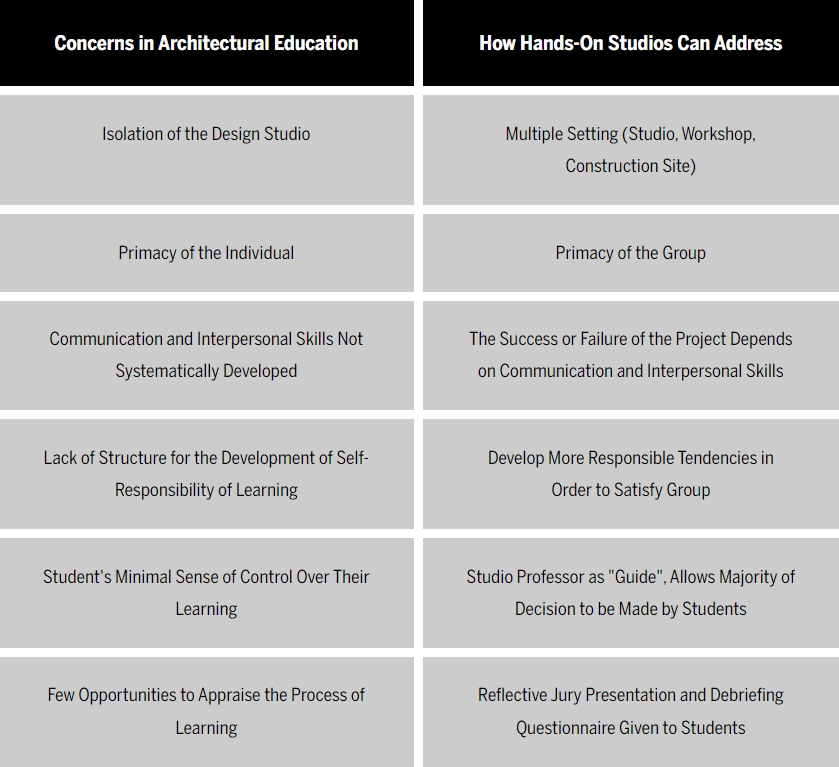

In their book Changing Architectural Education: Towards a New Professionalism, David Nicol and Simon Pilling bring together architectural educators, practitioners, and researchers to reflect on the previous century of architectural education. The essays outlined current issues of concern in architectural education including the following:

- Isolation of The Design Studio

- Primacy of The Individual

- Communication and Interpersonal Skills Are Not Systematically Developed

- Design As Product Rather Than Process

- Lack of Structure for the Development of Self-Responsibility In Learning

- Student’s Minimal Sense of Control Over Their Own Learning

- Few Opportunities to Appraise the Processes of Learning

The internal focus of the design studio, and the students’ long hours at the drawing board, produce students who become isolated from the outside world, learning only how to talk to architects. In stark contrast to this emphasis on self, the architect’s role in the profession is more aligned with a “translator” or “integrator,” drawing together people, process, and place in order to create a coherent working environment.

With the elimination of apprenticeship culture and the profession’s increasing speeds of production, architecture firms need entry level employees who can produce billable work. This puts more pressure on the education system to teach students professional concepts in the same time frame before graduation. What better simulation for the multiple environments and perspectives experienced in the profession than a hands-on studio with its often three distinct settings of Design Studio, Workshop, and Construction Site?

HANDS-ON STUDIOS AS PERFORMANCE ART

Designing – Script Writing (STUDIO) | Proto-Typing – Rehearsal (WORKSHOP) | Construction Process – Performance (CONSTRUCTION SITE) | Reaction to Reviews – Reflection (PRESS / SOCIAL MEDIA)

Hands-on studios move through processes of design and reflection during the semester, slowly moving closer to a full-scale built reality. The studios often begin with a playful introductory material exploration project akin to improvisational exercises of the performing arts. These exercises are used to explore ideas and grasp what the students know and don’t know about the problem at hand. Next, the group moves to designing a structure for a “real” client. This process resembles the script writing process. Once the major plot lines and concepts are defined, the studio begins to rehearse, much like a cast prepares for theater production, by fabricating full-scale pieces in the shop. Prototyping allows the group to better understand their design and further inform the “script writing” process. Following the preparation of shop drawings, representing the completed script, the group is ready to begin construction, or the architectural performance. In conclusion, the group presents the completed project including descriptions of client, invited members of the architecture faculty, and peers. This phase can be compared to a reception following a theater performance in which the actors celebrate the completion of the performance, reflect on the production, and await critical reviews.

The roles played by students in a hands-on studio can be compared to the performing arts. Firstly, there is a client or producer who commissions the work. The students’ and professor’s roles can be divided into 5 categories:

- Designers / Script Writers (Design Oriented Students)

- Architect / Director (Professor or Student with Construction Experience)

- Project Managers / Assistant Directors (Responsible but less Design Oriented Students)

- Skilled Trades / Lead Actors (Talented Students Interested in Developing Making Skills)

- Apprentice / Supporting Actors (More Observational Students Timid to Engage)

I equate designers to script writers. This position is first filled by each student designing individually, then everyone working as a group, and finally, a select group of students that choose to refine the design decisions. There is also a director or architect that oversees the day-to-day progress of the group and offers advice when appropriate. This role has been filled by the instructor and a student with extensive construction experience. A few assistant directors emerged as the students who typically took the responsibility of keeping the group organized or on task. From there, the group can be split into lead actors and supporting actors. Lead actors take on various leadership responsibilities such as refinement of the design and construction of specific parts of the projects, or completion of the shop drawings. The supporting actors are typically active fabricators during the rehearsal and construction process and take on other ad hoc responsibilities as needed but learn in a more of an apprentice or shadowing style.

Thomas Fisher, in his work In the Scheme of Things, considers design as a performance art and not as simply a visual one. He explains, “Unlike the notion of an individual creation prevalent in most of the visual arts, the performing arts offer a model of an inherently interdisciplinary, collaborative art form. Buildings or landscapes, as we know, never arise from the mind or hands of one person. In that sense, they are not like a painting or a sculpture, but rather more like putting on a play, involving designers, contractors, consultants, and clients much as staging a drama involves writers, performers, lighting/set/costume designers, and a receptive audience.”

Fisher puts out a call-to-action proclaiming, “We should attend to how students communicate to various audiences, how they work together on projects as a cast, and how they address the performance of what they do as well as its form.”

A CALL TO REFLECTION OR ACTION

In this article, we have reviewed the nature of hands-on studio education, the diversifying role or image of the architect throughout history, issues of concern in architecture education at the beginning of the 21st century, and the theory of architecture as a performance art. It is my hope that the next time you see an Instagram post with a shiny new tiny house or biomorphic shade canopy designed and built by students, you will consider the multitude of experiences and challenges those students learned to navigate. That the next time you interview a potential intern with a hands-on studio project in their portfolio, you will value the persistence, problem solving, and real-world teamwork they experienced along the way. As you design our city’s next library, plan our next public park, or negotiate our next urban design policy, you will reflect on the following:

“What if buildings were considered not as objects but as actors in the city, which perform with and among people in the small improvisations of urban life? What if design focused on how architecture acts, even without moving, in a thousand stories depending on the people, the place, and their interactions in the moment? From this point of view, an architect is akin to a theater director for he or she develops a building within a narrative of use, so that it may interact meaningfully with people and place.” – Gray Read in the Introduction to Architecture as a Performing Art

FURTHER READING ON DESIGN-BUILD (HANDS-ON STUDIOS) IN ARCHITECTURAL EDUCATION

Nils Gore, “Craft and Innovation: Serious Play and the Direct Experience of the Real,” Journal of Architectural Education (September 2004), no. 58/1 (2004).

Joseph Bilello, “Learning from Construction,” Architecture (August )(1996).

DesignBuild Education, ed. Chad Kraus (London and New York: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group, 2017).

Thomas Fisher, In the Scheme of Things: Alternative Thinking on the Practice of Architecture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006).

Gray Read, “Introduction: The Play’s the Thing,” in Architecture as a Performing Art, ed. Marcia Feuerstein and Gray Read (London and New York: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group, 2013). pp. 1-12.

Jori Erdman and Robert Weddle, “Designing/Building/Learning,” Journal of Architectural Education (February 2002), no. 55/3 (2002).

Architecture LIVE Projects, ed. Harriet Harriss and Lynnette Widder ((London and New York: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group, 2014).

William J. Carpenter, Learning by Building: Design and Construction in Architectural Education (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1997).

David Leatherbarrow, “Architecture Is Its Own Discipline,” in The Discipline of Architecture, ed. Andrzej Piotrowski and Julia Williams Robinson (Minneapolis: University of Minneasota Press, 2001).p. 87

Brian McKay-Lyons, Ghost: Building an Architectural Vision (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2008).

Andrea Oppenheimer-Dean, “The Hero of Hale County: Interview with Samuel Mockbee,” Architectural Record (February), no. 189 (2001).

David Nicol and Simon Pilling, “Architectural Education and the Profession: Preparing for the Future,” in Changing Architectural Education, ed. David Nicol and Simon Pilling (London: Spon Press, 2000). pp. 6-13.

Dana Cuff, Architecture: The Story of Practice (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1991).

Spiro Kostof, The Architect (Oxford: Oxford University Press,1977).

Andrew Saint, The Image of the Architect (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983).

Mary N. Woods, From Craft to Profession (Berkeley:University of California Press, 1999).

Dana Cuff, Architecture: The Story of Practice (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1991).

Ernest L. Boyer and Lee D. Mitgang. “A Profession in Perspective.” In Classic Readings in Architecture, edited by Jay M. Stein and Kent F. Spreckelmeyer. 492-509 (Boston:WCB/McGraw Hill, 1999), 500.

Ernest L. Boyer and Lee D. Mitgang, Building Community: A New Future for Architecture Education and Practice. (Princeton: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, 1996)