Artistic Explorations in Architectural Delineation

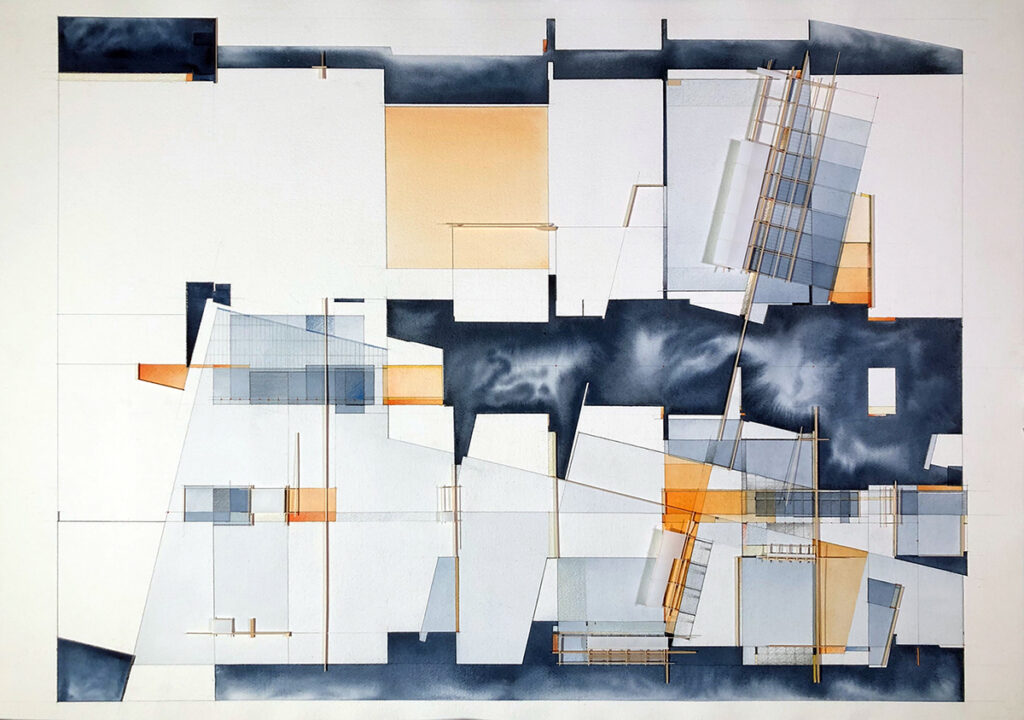

Untitled, by Brad McCorkle

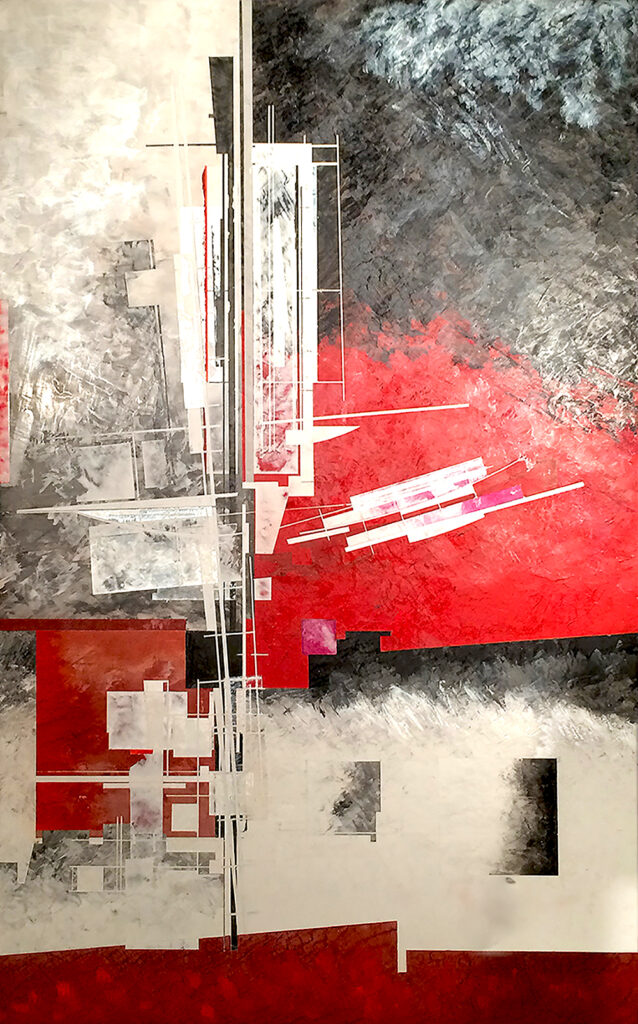

Untitled, by Brad McCorkle

Compared to most university architectural programs, the College of Architecture, Planning, and Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Arlington has a distinct style when it comes to the artistic output of its students. Visual communication is strongly emphasized, thanks to a faculty that teaches a variety of techniques to help students generate concept drawings and analytical models.

Adjunct Assistant Professor Brad McCorkle and Associate Professor Steven Quevedo have been key figures in this most fundamental of tasks. Both have taught at UTA for over two decades, and both were students of Richard B. Ferrier, FAIA, who taught generations of students at the school during a long, illustrious career.

In addition to his many works of delineation and watercolor executed in his signature style, Ferrier instilled in his students the importance of exploring architectural ideas using all kinds of media. His works garnered praise through dozens of AIA Dallas Ken Roberts (KRob) Memorial Delineation Competition awards and found permanent homes at the University of Houston, the AIA National Archives, and even the U.S. Library of Congress. Ferrier also enlisted Quevedo’s and McCorkle’s help in realizing architectural designs for clients through Firm X, his personal practice outside his teaching duties.

Toward the end of Ferrier’s career, McCorkle became his primary collaborator, working through and resolving his mentor’s rough sketch concept for each piece. He continued this style after Ferrier’s death in 2010 but developed it further by making it more layered and complex, covering more of the picture surface. McCorkle expanded Ferrier’s investigations into the use of the third dimension to what was previously a flat drawing, carving away select areas of watercolor paper or adding basswood pieces above the surface.

“Since the work is an exploration of architectural ideas, structure, section, layering, grids, and juxtapositions, it is important to bring the third dimension into the work, blurring the line between drawing and model, to better investigate their relationships to each other,” McCorkle says. “It allows for a clearer understanding of their interactions and spatial implications than simply drawing in 2D.”

Looking closely at the thin wood model bits floating over the gradient tones inherent in watercolor or carefully shaded graphite that define McCorkle’s style, the viewer instantly perceives a form of optical illusion, bringing you into a dynamic inner world of lines, surfaces, and space.

The composition is the third in a series of blue and orange paintings. The primary generator for the drawing is the exploration of section (dark areas) and its interaction with the grid, rotations, layering, and physical constructs. The frame is pine with purpleheart inlays that relate back to the drawing, making it an extension of the composition. Watercolor, graphite, color pencil, basswood, and vellum

While McCorkle’s pieces a retain a consistently delicate quality, Quevedo opts for strikingly bold composition, texture, and visual complexity. “The plaster paintings start as photo montages, which are constructed on board from images which incorporate construction, frames, structure, and surfaces,” he says. “These are then scanned and further manipulated in Photoshop. The images are then printed on Strathmore in a low resolution and then redrawn to investigate new forms and spaces. They are also transferred to the plaster surface by Xylene and redrawn to generate new compositions.”

“El Paso” is part of a triptych of paintings that examines the section and site plan of imaginary walls. “The ongoing political discussion of border walls has always been an interest to me, as it was the subject of my graduate thesis. The wall is not so much as a barrier between two countries but an architectural instrument in which to stitch two countries together,” Quevedo says. The painting is 27.5 by 44.5 x 0.75 inches. The media is plaster with integrated pigments, acrylic and metallic paints on Baltic birch plywood.

Closer inspection reveals intricate graphite drawings depicting abstracted plans, sections, and elevations of structures often intersecting and overlapping each other. Quevedo explains that these orthographic projections “are speculative in nature about architectural forms.” Together with this mix of textures, datum lines, axes, and superimposed drawings, each work contains a strong collage-like quality. Quevedo argues that “montage and collage provide moments of the unexpected. Arranging varying elements and trying to assemble them into new spaces and forms result in discoveries not premeditated. Trying to design them into a comprehensive composition becomes an interesting design challenge. They could be facades, city plans, excavations.”

The inclusion of the last item reveals Quevedo’s careerlong explorations of ancient structures, which led him to work with joint compound as his preferred base material. He further clarifies: “I originally started to work in joint compound first because of the texture of the surface. The sanding leaves slight infractions, which the graphite can then be used to create small details and patterns. From traveling to Italy and seeing the beautiful Venetian plaster of the architect Carlo Scarpa, I learned to mix natural pigments in plaster, which can be burnished to a smooth surface resembling marble. The process is called marmolino. In the experimentation from the montages, it seemed like a natural next step to investigate the montages in painting, exploring surfaces and materiality.”

Both McCorkle and Quevedo can use architectural drawing as a point of departure for exploration into more concepts and themes. Each can produce work that shows a unique artistic focus, even as they both employ common elements such as regulating lines, fragments of buildings, composed in a rigorous architectonic style first developed by their mentor. The result are pieces that are both highly ordered and delicate. The fine linework, layers, textures, careful shading, and gentle tones invite you to come closer and uncover an intimate inner world that is tactile, colorful, complex, and infinite.