Narrative Mapping

Narrative mapping has become a new facet of cartography that augments objective reality by storytelling through subjective perception. Traditional cartography maps physical environments in states of stasis within particular moments in time; our realities, however, are not solely objective or static. They are always in flux. While they negotiate often with physical geography; they are more accurately defined by the intimate links between history and memory as they relate to changing geographies over time. Narrative mapping seeks to reimagine geography and investigate ephemeral operations, while juxtaposing the historical and the contemporary1 and liberating phenomena from the encasements of convention.2 This reimagining of how we choose to map our realities actually better helps us to tell the stories of those who cannot so easily tell them on their own.

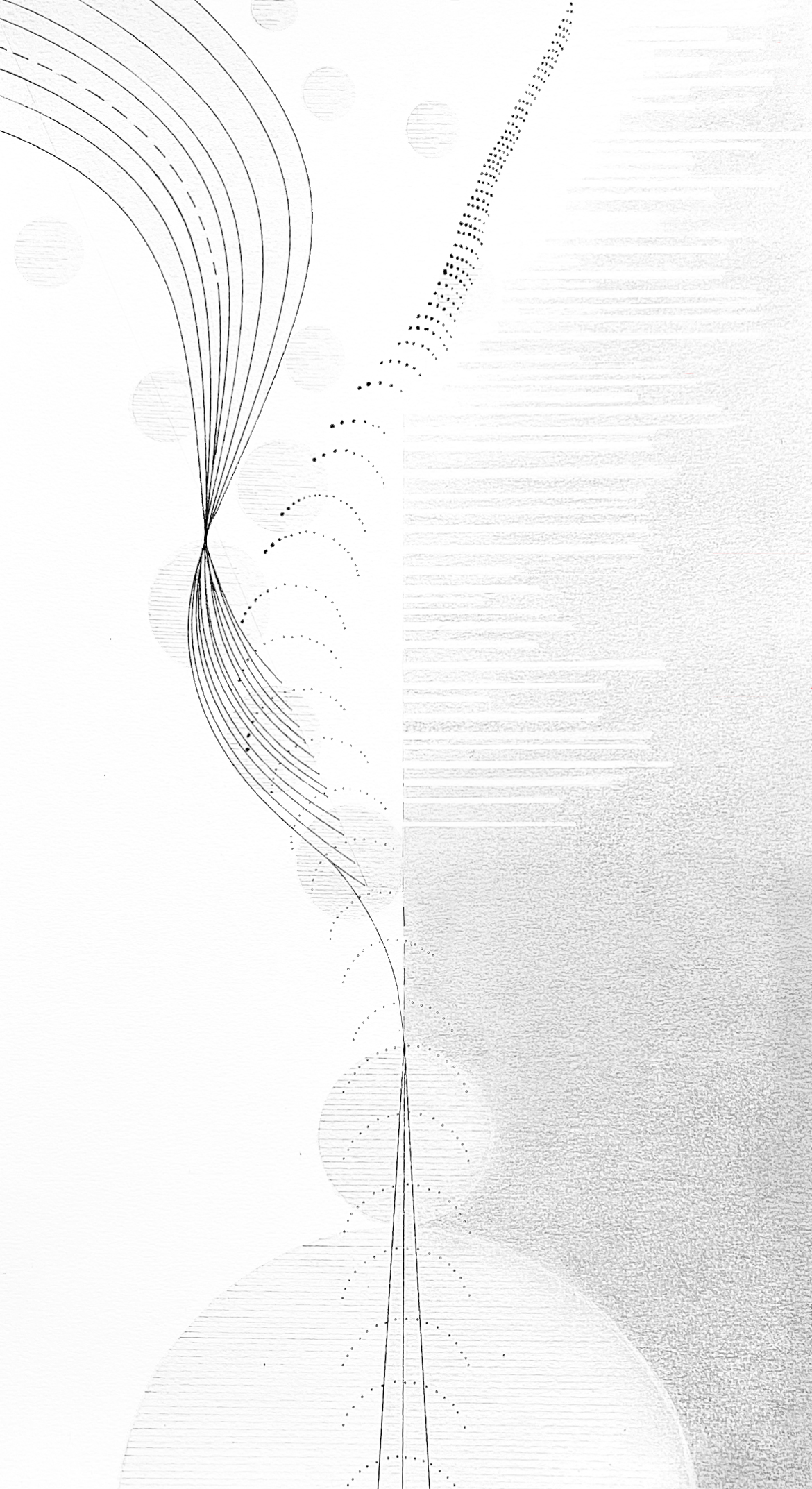

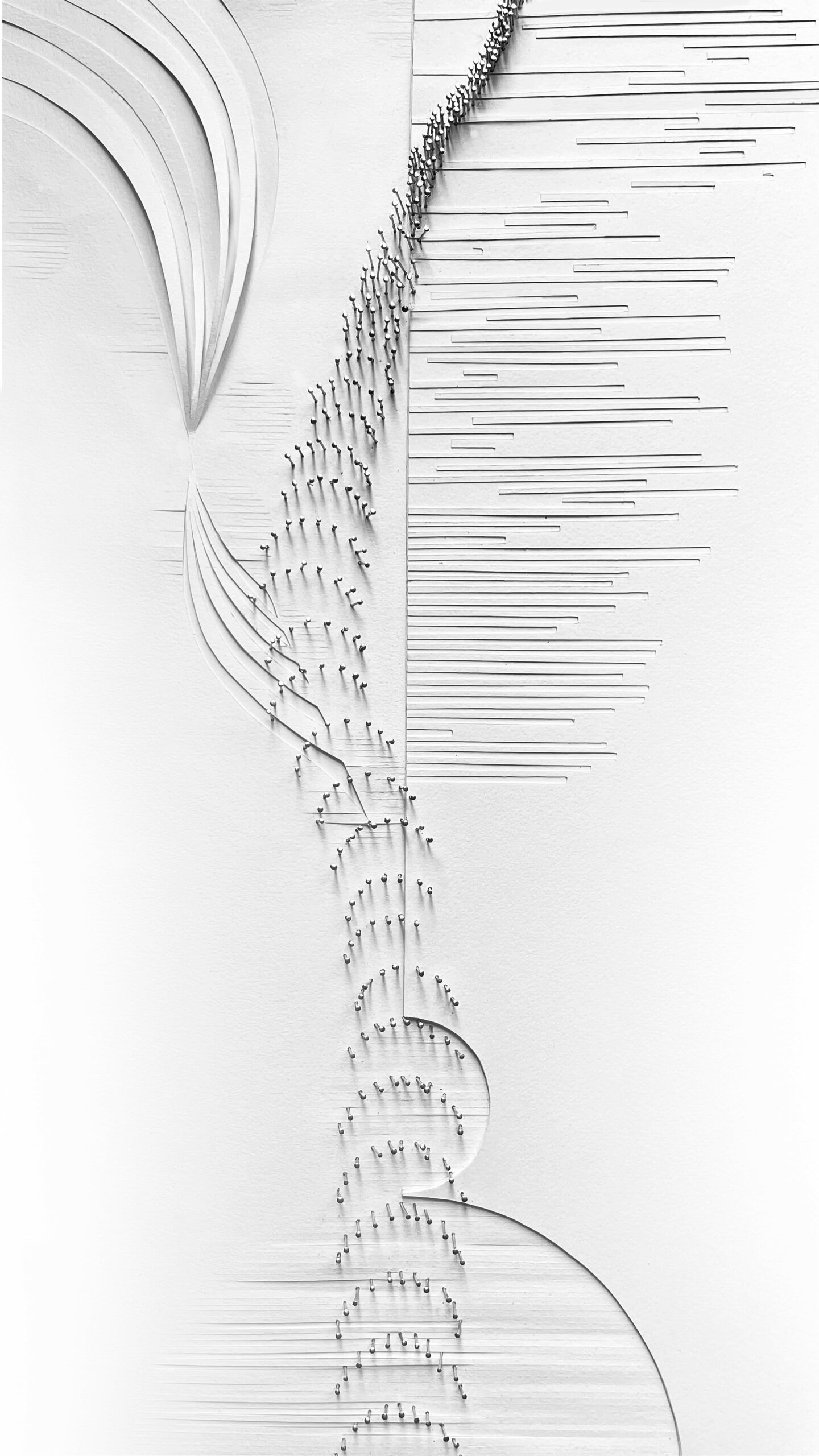

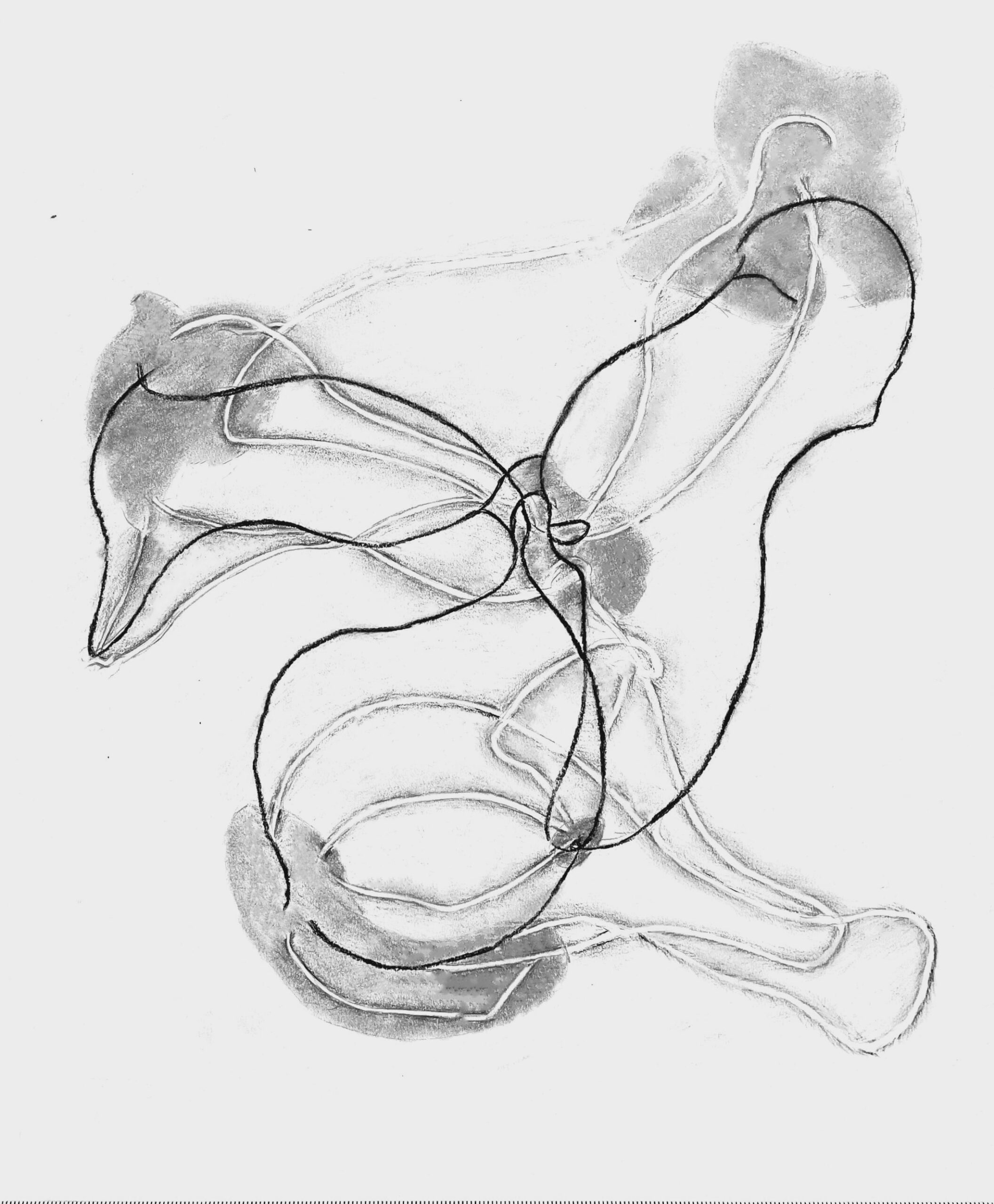

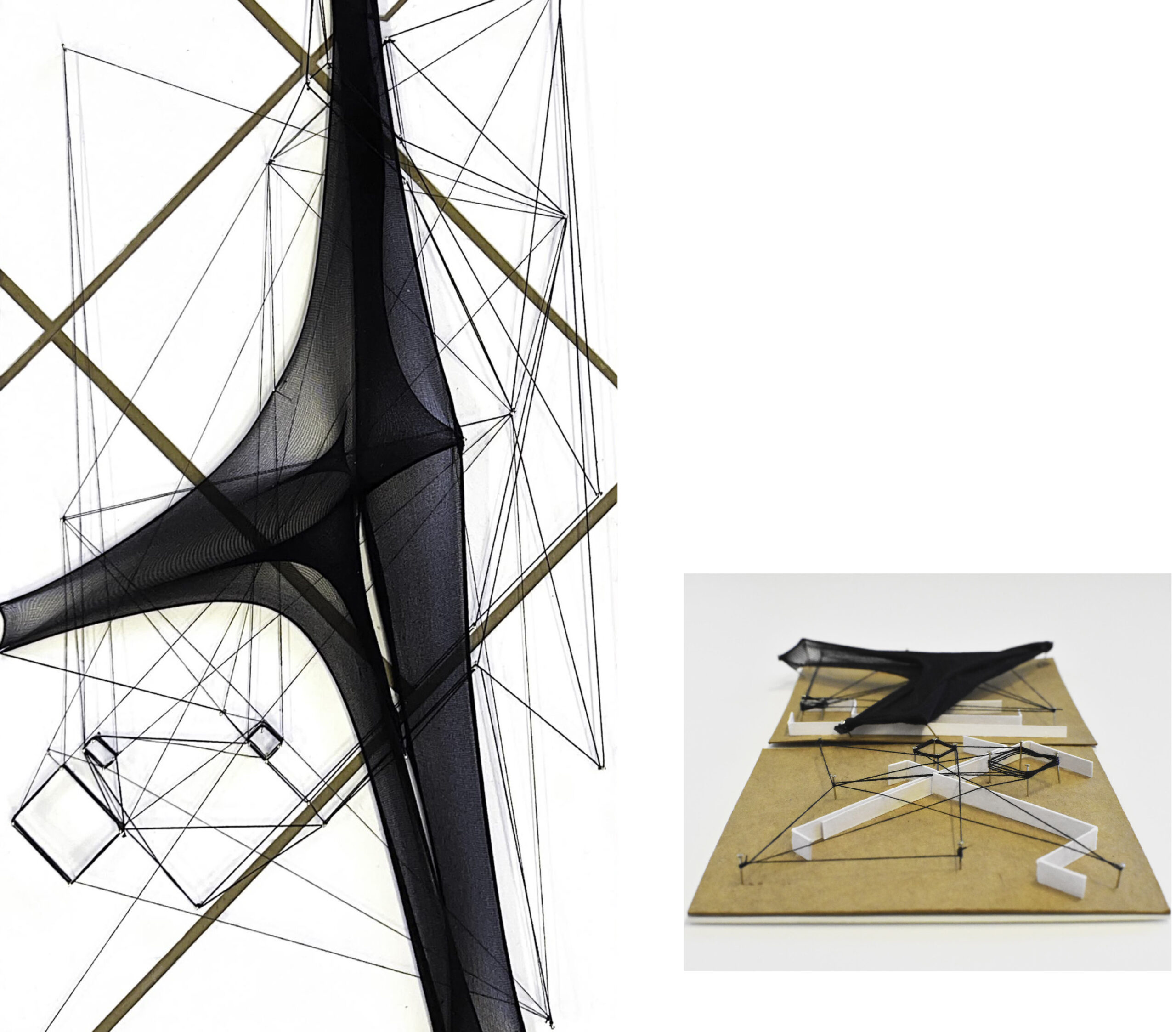

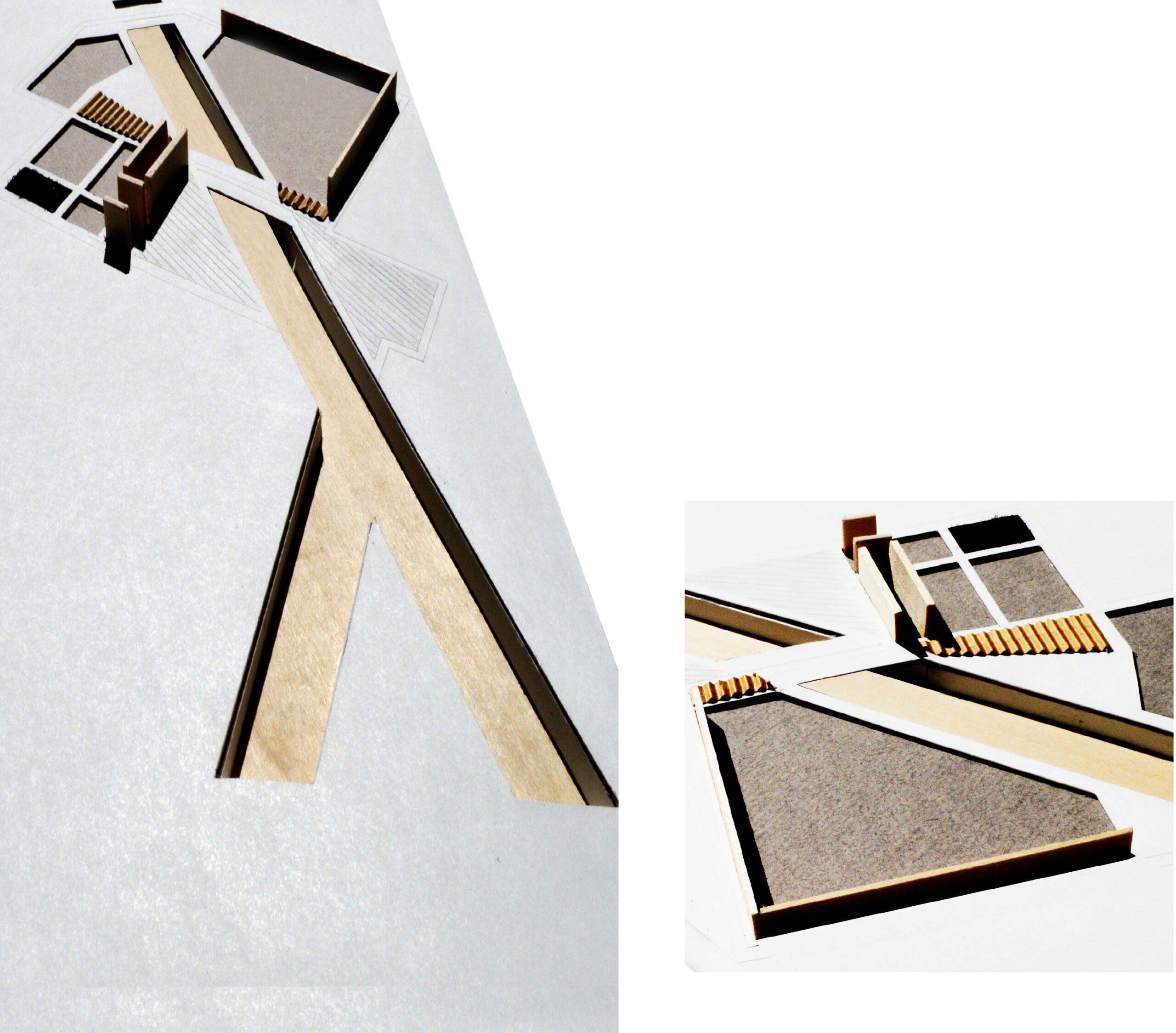

The narrative mapping process requires a balance between the interpretation and editing of archival maps and documents, various scales and types of datasets, and the recording of oral histories interlaced within those geographies. This interpretation, editing and distillation are all invisible but critical processes. A particularly novel take on narrative mapping seeks to reimagine places as defined by agents of space and time specific to those contexts. The process utilizes a combination of drawing and physical modeling whereby a set of graphic and dimensional rules are generated that begin to codify, abstract, and give form to each agent. In the practice of research, as well as in an academic design studio setting, this begins as a drawing that evolves into a hybrid relief modeling exercise that collates these abstracted agents into a system by imagining their invisibility and temporality becoming visible and permanent upon the landscape. Continual editing transitions from the mapping of physical geographies to ephemeral geographies, creating a spatial palimpsest that tells a more accurate story of the place being mapped. The result is that known boundaries shift and blur, systems and relationships become graphically intertwined and dependent upon one another, spatial and cultural narratives become clearer, and memories become materialized.

Mapping agents of both space and time warrants representation that accounts for change. For this reason, the identification of geographic commonalities, both those that change and those that remain over time, are paramount. Infrastructure and rivers, for example, exemplify this category of geographic commonalities as they both serve as agents of a larger framework that histories are tied to. Selective development patterns and shifts in ecological composition then serve as agents of context. Jumping down in scale, key architectural nodes and landscapes are physical manifestations of our histories providing specific anchors for elements extracted from oral histories. The physical manifestation of memory then becomes an important next layer wherein oral histories that reveal traditions, patterns, and stories become spatially communicated. The mapping of historic walking paths, for example, spatially communicates a number of human-centric behaviors and patterns that change over time and can also begin to reveal hidden realities that geographies are void of. These hidden realities are the backbone of narrative mapping; they are not known from the beginning but are rather discovered through the process and hold immense value in storytelling.

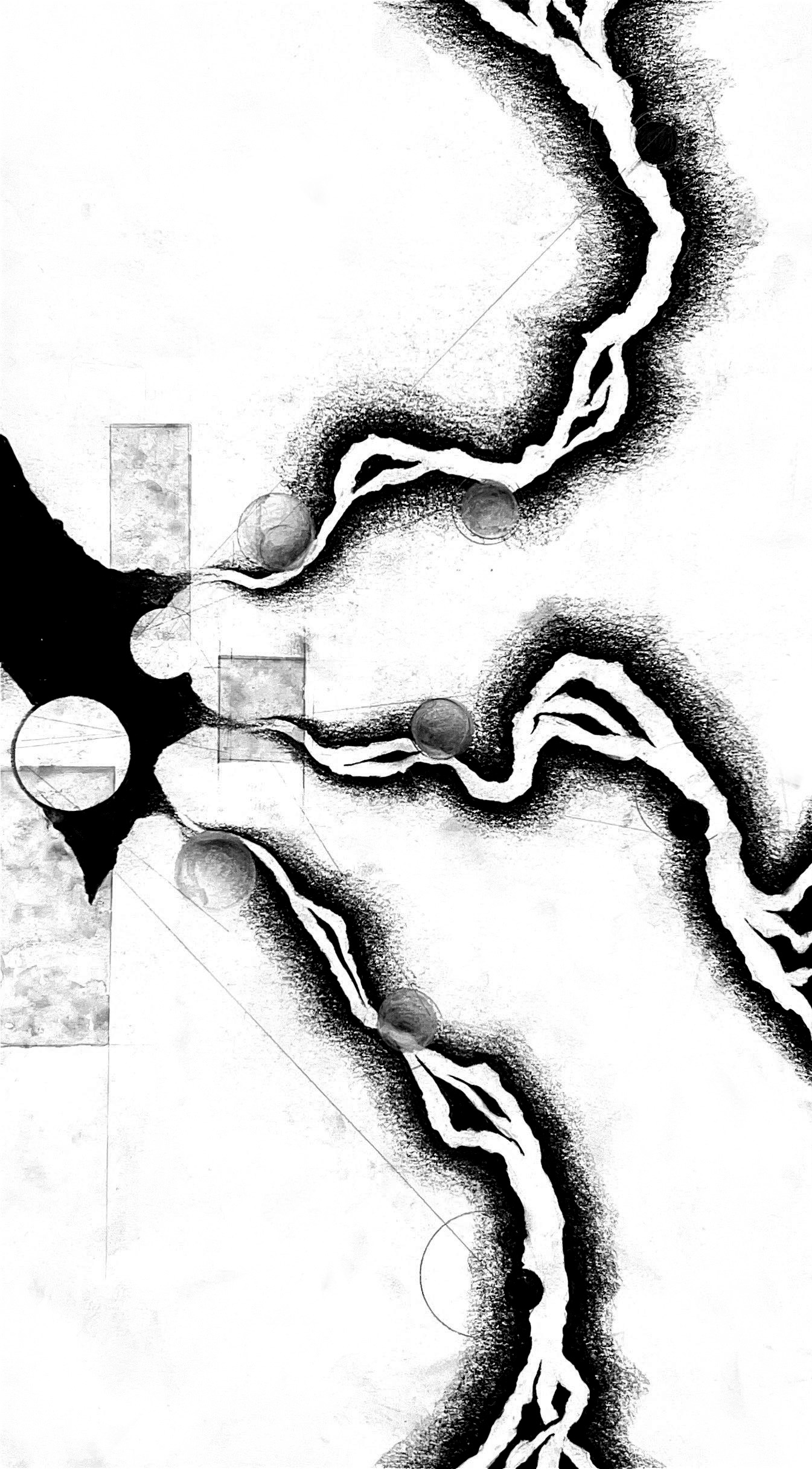

Rivers are often anchors for this kind of process. Unlike some of the most productive and operative river landscapes in the United States, such as the Mississippi River and the Hudson River, the Trinity River exists more as a ghosted relic that reveals only remote traces of a past life. It has only slightly emerged from a shallow grave in recent years, but severely lacks an authentic reading of who it has truly served and belonged to. Its watershed traverses a landscape that was once a complex network of Indigenous civilizations that cultivated and cared for the land; its productivity was a function of an ecological and anthropogenic symbiosis. It cradled cultivated fields from the fallow alongside Freedman settlements, tethered to rail lines emerging from an industrial spirit. It sacrificed much if its adjacency to the strip mining of gravel for the building of Dallas and Fort Worth, leaving a novel ecology of ruin in its wake. Histories and ecologies were altered and forgotten, leaving its landscapes without a real understanding of their own stories and those of the people living within them.

Storytelling on behalf of a collective of Freedman settlements along the Trinity River relies heavily on this narrative mapping process. Agents of space and time mapped together create a textured reality from the interlacing of physical places and temporal relationships, as well as through memory and oral histories. It results in a translucency that mimics the passing of time, allowing for moments of both clarity and turbidity. This operation helps to reveal how events from long ago, though not as easily remembered, still live in the subconscious of the life of these settlements, and ultimately lay the groundwork for their identity.

In a recent design studio, students were tasked with narrative mapping a particular settlement, Freedman’s Town, located in and around what is now the Arts District and State-Thomas Historic District of Dallas. The community thrived for decades, reaching its peak in the 1930s, navigating the creation of their own social and cultural institutions in spite of the segregation set in place. However, the construction of Highway 75/Central Expressway in the 1940s bisected the community, leading to its long decline, forcing the relocation of residents to other settlements in South Dallas and along the Trinity River. Today, the only physical remnants of the neighborhood include Booker T. Washington High School (though relocated), St. Paul United Methodist Church, Moorland YMCA (Dallas Black Dance Theatre), and a number of historic homes in the State-Thomas Historic District.

The Trinity River, the geographical anchor for these narratives, also serves as an agent in the course of its own story. Rivers are often employed as cartographic boundaries—they demarcate edges and peripheries of both occupied and geopolitical space that ultimately inform various categories of other boundaries. Their agency to bound, however, has shifted over time. In particular, the Trinity River was once a permeable edge, serving as a fluid conveyor of people and goods which helped to flourish its adjacent ecologies, both human and non-human. With the construction of the highway system, using materials harvested from the Trinity River, and the departure of Freedman communities, the river transitioned from a productive agent in the landscape to a near fortified edge that categorically altered the operation of conveyance and ultimately transportation. Fluidity and porosity gave way to barrier and division, a shift that laid the groundwork for decades of inequitable planning and development that have proven incredibly difficult to reverse. The story of the Trinity has had a profound impact on the stories of the communities inextricably linked to its depleted landscapes; it is through narrative mapping that the impact of the story is revealed and materialized in these communities.

With this story in mind, students began the mapping process by studying historic Sanborn maps, a series of large-scale maps dating from 1867 to 1999 which document commercial, industrial and residential buildings and their respective construction types, locations of windows and doors and sprinkler systems. These maps were made to assist fire insurance agents in determining the degree of hazard with particular properties but have been immensely informative in mapping cities over time. In addition, students collected written accounts and watched documentaries to reconstruct narratives of the Freedman’s Town community through a number of lenses. Layers of data extracted and mapped together revealed narratives of migration, social infrastructure, spiritual growth, business and medical pursuits, and of faithful perseverance. Narrative mapping collated this data into storytelling devices that enabled students to experience a new way of understanding a place outside of just its physical geography. They became attached to the realities that they were mapping. In this materialization of memory, they began to advocate for a deepened perspective of architectural design and ultimately for a more just world. One project studied the relocation of families from the neighborhood and followed the demolition of their homes through Sanborn maps and tracked land survey data. The lots of these family histories became the focus for an architectural intervention that framed the voids as spaces of memory and reflection. The introduction of varying depths of water would, throughout the course of each season, reflect the changing landscape while holding, in its fixed place, a memory of permanence.

In the construction of contemporary urban environments, narrative mapping is a critical necessity. It tells the story of the place being designed, reveals its histories, foregrounds the memories of its inhabitants, current and past, and ultimately communicates its voice that is likely underrepresented within the context of the larger environment. Without acknowledging these in the design process, we run the risk of vastly misrepresenting places and veiling their histories that texture our cities rich in identity. Without identity, the practice of placemaking falls short as these places are left to be perceived against a fictional background that promotes singular design strategies and policies s devoid of equity and accurate representations of what really makes a place.

The proposed planning for the Trinity River would greatly benefit from narrative mapping, for example. The story of the Trinity and its communities is vastly unknown to those that will occupy the future version of this project. To them, it may otherwise just be a park landscape meant to resurrect a utilitarian riverbed—a project that could exist in tandem with virtually any urban river in the U.S. But here in North Texas, the specificity of its histories and the memories of its inhabitants define its identity, one that wholly informs it as a place. Placemaking is ultimately the materialized derivative of a story and, when told through the lens of narrative mapping, it is the story that connects the place to the visitor and passerby willing to lend an ear. It is this connection that enables us, as designers, to advocate for the places and people we design for. The details, patterns, and memories that create our realities have spatial implications because they operate within both space and time simultaneously. We have great influence on our geographies, as evidenced by our heavy-handed operations on the earth from the first moment we were capable. But our geographies also have great influence on us—they are the framework, albeit one that is ever-changing, that ultimately give our memories a place to land.