Painting on the Wall

Good-Lattimer Tunnels // Photo by Justin Terveen

Good-Lattimer Tunnels // Photo by Justin Terveen

As long as man has had the inclination and desire to create art or to visually record the world around him, walls have served as the original canvas. The painting of walls adorns a space for any number of reasons, from the religious to the display of personal wealth. Its large format provides a sizeable surface on which to provide artistic expression and thus a grand statement for both the artist and the commissioner. It is natural then that wall painting and architecture should go together, with the former providing an additional two-dimensional layer of texture to a form of design that deals with the creation of space with three-dimensional tectonics.

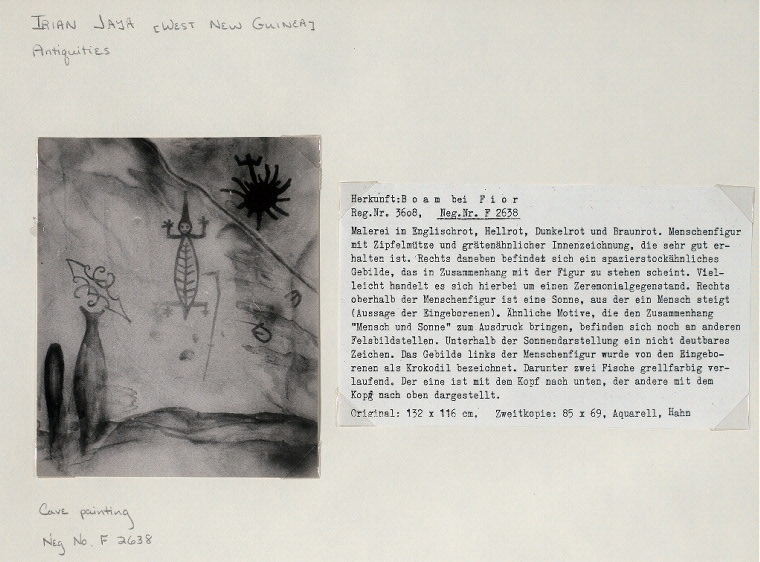

The human instinct to mark the walls of their spaces is nothing new. The earliest cave paintings originated over 160,000 years ago, and since then humans have used walls to tell stories. Over the millennia, frescoes and murals have served to represent a variety of messages, including the outward display of wealth, religious storytelling, the history of a place, and in the current moment, the opportunity to stage a photo for social media.

Adorning available surface was essential to sacred buildings as they not only illustrated the world view of the people who built the walls and ceilings, but also instructed worshippers within the structure of their metaphysical universe.

Temples in all ancient civilizations were rich containers of imagery, whether with colorful painted scenes, mosaics, or reliefs sculpted onto the surfaces of their columns, beams, and especially walls. Even the stark white ancient Greek temples that still stand around the Mediterranean were once covered in vivid pigments, with their friezes and architraves embellished with stories about their gods and heroes.

Murals weren’t limited strictly to the sacred realm. They were just as much a part of the domestic realm, where home interiors became a free canvas that provided a pictorial background to the activities that took place. Along with continuing their predecessor’s architectural tradition in the design and construction of their religious structures, the ancient Romans developed a sophisticated tradition of interior murals, particularly within the lavish residences of its social elites. A striking example of this can be seen at the Villa San Marco in Stabiae near the city of Pompeii.

The frescoes of Stabiae, an ancient luxury enclave on the Bay of Naples, are notable for their opulence and conveyance of wealth. The villas of this enclave were occupied by the Roman elite during the Roman empire, and the frescoes depict subjects ranging from the production of wine by the god Bacchus to figs resting on a shelf, waiting to be eaten (presumably paired with the wine, production overseen by Bacchus). The murals take on different significance in terms of their spiritual connection to the divine but are no less impactful in terms of making use of the architecture of the dwelling to serve as a surface on which to impress.

This particular class of elite Romans built their villas not only to display of their wealth but also as an assertion of their political prominence. According to Thomas Noble Howe, Professor of Art and Art History and chair of Art History at Southwestern University, the houses, “were as much instruments of their social power as they were places of luxury and retreat.” Thus, the art showcased within their villas had to reflect their projected values; portrayals of sophistication and scholarship, poetry and material goods, were all on display in the architecture of the house. Roman gods and goddesses flanked various walls and bestowed virtue and good tidings upon the inhabitants, while tiny nooks featured birds or visual representations of architectural vocabulary.

As centuries passed and the city was transformed by the industrial revolution at the turn of the twentieth century, murals migrated from the home to the casual public realm of emerging industrial and commercial districts. The utilitarian character of new building types, such as warehouses with unadorned facades, provided many opportunities for beautification and community identity through art. After these areas experienced the exodus of their original industrial uses at the end of that century, murals consisting of pictures and bold text graphics were essential in adding layers of meaning to an inherently bleak built environment. The United States has a rich heritage of promoting murals as a way to enliven the cultural vibe of its cities.

MURALS IN DEEP ELLUM and TUNNEL VISIONS CASE STUDY

In Dallas, the surfaces we find about the city are not so different from those found in the Mediterranean. The walls of the Deep Ellum neighborhood serve as usable canvas space for painted signs and advertisements, and it’s only natural that they would also serve as canvas for self-expression. Deep Ellum is a neighborhood known locally for its rich demographic history, as well as its deep artistic and industrial roots. As an area that was settled around a railroad junction in the late 1800s, it served as a literal crossroads. The railroad brought a creative class and the earliest blues musicians in North Texas. The predominant art form in the area was music—blues and jazz—that was enveloped by a layer of industry and warehouse building types. As the development of the automobile progressed and space dedicated to manufacturing and assembly grew more ubiquitous, so too did the brick warehouse and factory building types. These buildings, with their expanses of woven brick envelopes, easily lent themselves to visual decoration and advertising, and later to creative expression.

By the late 1960s, the area had seen a rotation of business types and demographic shifts. The construction of Central Expressway through the middle of the neighborhood all but obliterated what business was left in Deep Ellum. Finding empty buildings at fire-sale rent prices, a new creative class of musicians and artists moved in and began an urban renaissance in the 1980s. Among the pioneers of this new wave of artists was Frank Campagna, founder of Kettle Art Gallery. As a practicing artist, Frank was entrenched in the art scene and worked out of a studio in Deep Ellum. He was also intimately tied to the music scene, designing flyers and posters for bands that came to town. Eventually he combined the two—art and music—by using his studio space as a makeshift club called Studio D. This space saw performances from the likes of the Misfits, Dead Kennedys, and the Meat Puppets. With codes and concerns about occupancy at a low level due to the warehouse-ness of it all, Campagna was free to experiment with the textures of his neighborhood and his space. Over time, Frank and his peers saw the brick walls they occupied as ways in which to enliven the neighborhood, and bars and clubs such as Club Dada, Blind Lemon, and Trees became known as much for the bands they hosted as the paintings on their walls.

THE DALLAS MORNING NEWS > FROM THE ARCHIVES

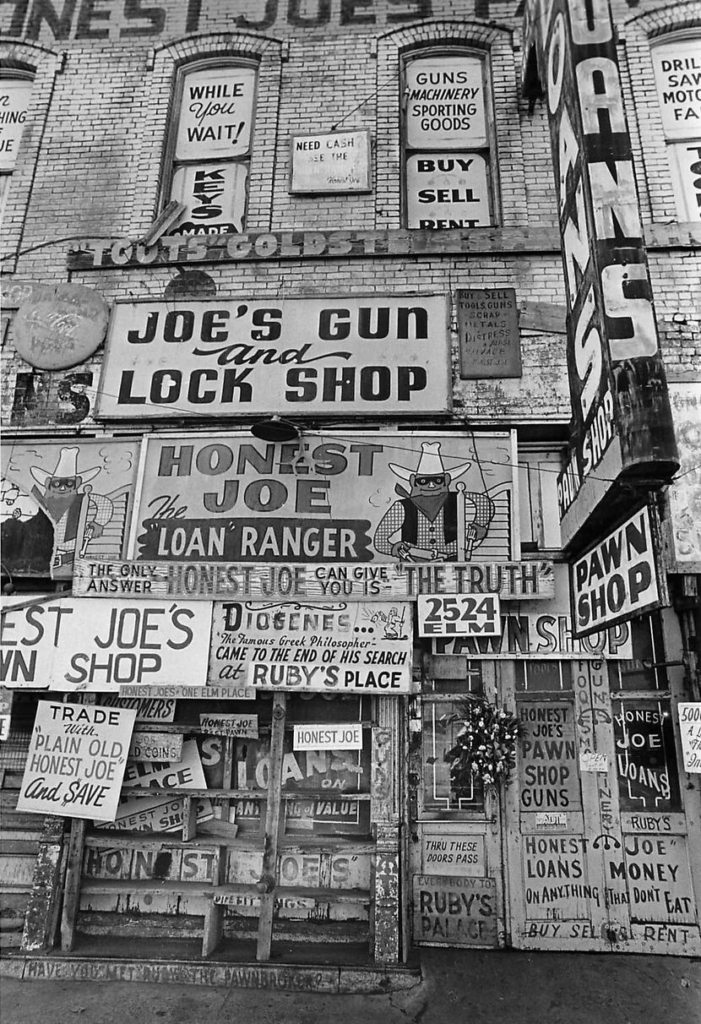

Where one man’s trash became another man’s treasure: Pawnshops lined Elm Street in Deep Ellum for decades

The stores played an important role in the neighborhood from the 1920s through the 1980s.

“Watch those bear traps when you walk through here,” pawnbroker Rubin Goldstein of Honest Joe’s warned Dallas Morning News staff writer Larry Grove in 1964, while he threaded his way through “the clutter of a million valuable items that bear a striking resemblance to junk.” This scene was common along Elm Street in Deep Ellum from the 1920s through the 1980s.

This group of young artists had the chance to use the architecture of the neighborhood to beautify it and to express themselves on a large scale. Those who were around during that time will remember the colorful reliefs of Club Dada and the bright signs of the Art Bar, the glowing lights of local head shops and clothing stores illuminating the club-goers and passers-by. Alley-facing facades that typically see dumpsters and the occasional stolen chance for urination were covered with painted homages to Blind Lemon Jefferson and Che Guevara. In a time before social media, these paintings were raw projections of musical heros and revolutionaries, texturized by brick, mortar, and the film of urbanity and car exhaust.

The gritty music scene taking place during the cultural renaissance of Deep Ellum during the ‘80s brought with it a fledgling development opportunity and ways in which to capitalize on some of the “leftover” spaces of the neighborhood. Developers saw such an opportunity in the Good-Lattimer tunnels, a non-descript concrete structure connecting downtown to Deep Ellum. Dark and fairly uninteresting, Frank was contacted as a potential muralist. Recognizing that he could not tackle such a project alone, Campagna mobilized his network of fellow artists to curate Tunnel Visions in 1993. The artists selected to paint the murals of the tunnels were not all muralists; there were painters, illustrators, and graffiti artists, and Frank was less interested in what kind of art they brought to the table than the kind of art they would leave behind.

Not unlike the residents of Stabiae, Frank understood that the visitors to Deep Ellum would be influenced by the images surrounding them and the manner in which it was executed. Armed with painting tools and open minds, the artists of Tunnel Visions took their ideas to the walls of the tunnel, imparting bit of themselves and their neighborhood along the way. The project was planned for one day, with each artist having selected their spot and designed their mural for that location. The end result was a half-mile array of works, fantastic illustrations and bright colors. The tunnels remained painted from 1993 onward, with three updates before the demolition of the structure to make way for the DART light rail in 2007. Longtime residents of Dallas cannot divorce their memories of Deep Ellum from the experience of passing through the tunnel to get to the neighborhood, or from the big, wide toothy mouth swallowing you whole before passing you through the guts of the painted passageway.

The Good-Latimer Tunnel Project, or Tunnel Visions as it came to be known, helped catalyze the modern use of murals to enliven the spaces in Deep Ellum, with subsequent programs such as the 42 Murals Project following in its footsteps. The use of painted walls has come to define the neighborhood, and it has been the unifying visual thread tying the decades of transformation together. In more recent years, the industrial grit has slowly been washed away with new buildings—high-rises, condos, shiny eateries and retail spaces. But in the narrow spaces and alleyways, the evidence of Deep Ellum’s past is still there, co-mingling with its present. Whether walking past a hundred-year-old brick wall with a mural painted in the ‘80s, the ghost of a painted ad behind it, or a freshly laid brick wall with a mural painted two years ago, the intent of the mural remains the same as that of a mural painted in Stabiae during the Roman Empire: to project a feeling of importance using paint as voice.