Some Buildings Are Special. Some are Not.

Image by Cody Ulrich

Image by Cody Ulrich

Sitting in the back row of a cramped, windowless, clammy classroom with flickering fluorescent lights, I was exhausted from a string of late nights in Studio. Our professor droned on and on about mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems, as I struggled to stay awake. On this particular day, he must have sensed our collective apathy because just as I was considering the feasibility of nodding off, he suddenly yelled “LISTEN! One day, very soon, you are going to be responsible for how the buildings you design perform! And you will be held liable if it doesn’t measure up to certain energy standards!”

As a nature lover and architecture student on track to earning a certificate in Sustainable Urbanism, his words struck me deeply. Over 20 years later, as predicted, our responsibility as designers includes ensuring our buildings meet high performance standards.

There are many performance aspects within the built environment that can be measured. It may be helpful to separate these into two categories – intangible and tangible.

Intangible aspects include qualitative data, like occupant surveys which measure the project’s impact on users. For example, classrooms with natural daylight often see improvements in student test scores, while stores with biophilic interiors increase sales. Tangible aspects are quantitative, using predictive modeling to evaluate factors like daylighting, energy use, and carbon emissions. Post-occupancy, these can be monitored via utility bills or sub-meters. This reflects the mantra: “If we can’t measure it, we can’t improve it.”

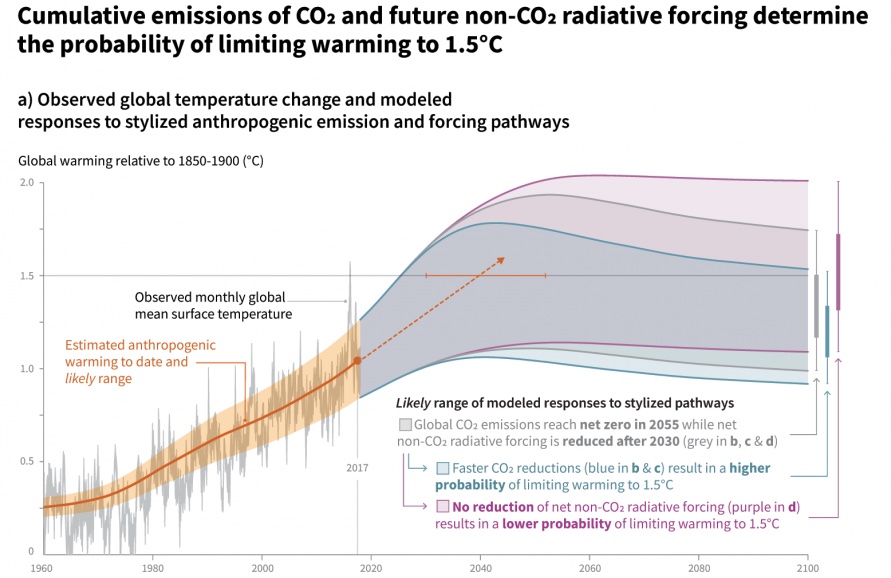

Measuring energy, carbon, and more is now standard practice for many firms and a requirement for the AIA Design Awards. This is crucial, as we must significantly enhance the performance of our existing building stock to cut global emissions in half by 2030, staying below the 1.5 degrees Celsius threshold set by the United Nation’s The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

As it turns out, my professor was only half right. While monitoring energy and operational carbon is vital, it is only part of the challenge. To meet our “carbon budget” we must also focus on embodied carbon and the reuse of existing buildings.

Imagine being on a fixed income, not just for you but for future generations. As a planet, we have a limited carbon budget, and last year we “spent” 41 billion tons of CO2. At this rate, we only have six years before we “go broke.” Therefore, it is imperative to reduce embodied carbon and reuse building materials to preserve our planet.

While there are many helpful tools and resources, I have found we usually learn best from examples. Therefore, we will examine two Texas case studies: the restoration of a historic hotel in Waco and the transformation of a warehouse into a high-performance office. These contrasting projects demonstrate that all existing buildings, whether unique or mundane, have value and can be repurposed into vibrant spaces that attract new life and community.

Hotel 1928

Design Team: Hartshorne Plunkard Architecture (HPA): Sophie Bidek, AIA (Partner), Andrew Shimanski (Associate Partner), Krista Weir, AIA (Director of Preservation), Janice Jones (Senior Associate); Developer AJ Capital Partners; Magnolia with Chip & Joanna Gaines

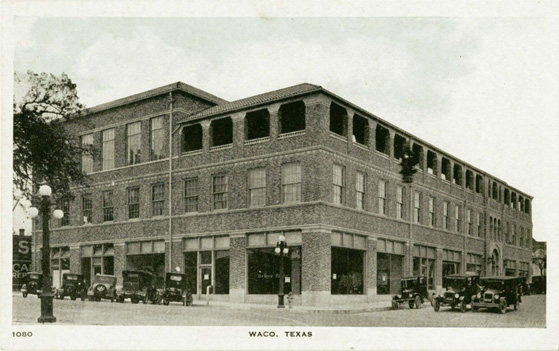

“Located at the intersection of Washington Avenue and N. 7th Street, Hotel 1928 is a contributing property in the Waco Downtown Historic District, listed in the National Register of Historic Places. It is one of at least 80 buildings in this district that were built between 1920 and 1929, one the largest building booms in Waco’s history,” said Krista Weir, RA, CDT with HPA.

Originally designed by the Dallas-based firm, Greene, LaRoche, and Dahl in 1928, the structure was designed “to support the Masonic organization’s social and philanthropic activities. The Karem Shrine Temple’s Moorish Revival style of architecture…includes three floors and a partial basement, featuring a rectangular plan, combination flat, hipped roof, and a square rooftop penthouse tower.” At the time, the building was mixed use including ground-level retail, a 150-person dining room, game rooms, administrative offices, meeting spaces, the Crystal Ballroom, and a covered exterior deck that overlooked downtown Waco.

The principal design directives were clear from the start. Firstly, to “preserve and integrate as much historic material as possible into a contemporary hospitality program,” and secondly to “install necessary upgrades, such as a new roof structure and building systems.” and thirdly, “create warm, community-gathering spaces throughout the building, even in spaces that had previously been back-of-house areas.”

HPA painstakingly worked to catalog and preserve the existing historic features while also providing an energy efficient building that exceeds today’s energy codes and extends to personal thermal comfort. For example, the Crystal Ballroom suffered significant water damage due to undersized roof trusses. The existing roofing was carefully removed to repair the structure, allowing the team to fully restore the existing plaster.”

The majority of the original windows were replaced long before the current owners bought the structure, therefore new windows were selected (with input from THC) “to both be acceptable from a historic perspective of transparency and reflectivity while also preventing excessive heat gain. “Additionally, during construction, the original wood transom windows were discovered behind non-historic paneling. A wonderful find, they were restored and new striped “awnings were added…to both protect historic transom windows and to provide shade.”

“All of the existing building systems were replaced and integrated around historic finishes. For example, in the main entry, the decorative stenciled ceiling pattern is original to 1928. The exposed beams are the building’s concrete structural system, and unpainted examples of the structure can be found exposed in other locations in the building. The design team routed all mechanical systems, plumbing from the guestrooms above and other systems around the volume of this room to protect the historic ceiling finish, existing plaster walls and original terrazzo floors.”

When we, as architects, encounter such a treasure, we are not just inspired but feel responsible to honor, respect, and return the building to its former glory for the new occupants, whomever they may be. This level of craftsmanship and detail would be almost impossible to recreate, and with the 100 years of embodied history, it would be irresponsible to do anything less.

Completed in 2023, Hotel 1928 now features thirty-three guest rooms, three restaurants, a ballroom, and a rooftop terrace within the existing 59,143-square-foot structure. The team took great care to restore and preserve every original detail. This project received the 2024 Design Award from the Texas Society of Architects.

“I was most impressed by the creativity of the renovation in terms of the found spaces—the idea that they not only enhanced what may have been there but elevated it to a more contemporary and consistent language, not just internally but also externally.”

— Gordon Gill, FAIA, 2024 TxA Design Award Juror

Fifth + Tillery

Design Team: Architect: Gensler, Original Owner: CIM Group, Current Owner: Capital Metro, Developer: 3423 Holdings, LLC, MEP Engineer: Arete, Electrical Engineer Lloyd Engineering, Structural Engineer: MJ Structures, General Contractor: RM Chiapas, Landscape Architect: Campbell Landscape Architecture

Upon completing my research and interviews with HPA on Hotel 1928, I set out to find an “opposing” example to the “special” building. My goal was to find an ugly and mundane building that through adaptive reuse or renovation is now an example of high performance and objectively beautiful.

Through my exploration, I found many great examples. Some projects adaptively reused mundane modern buildings and kept their historic integrity as the driving design principal. Others selected the building for reuse based on the shape of the space or its materiality. At the same time, it is important for our readers to showcase projects in our hot and humid climate. I personally have rolled my eyes at amazing Net Zero Projects in temperate projects of Portland, Oregon and said to myself. ‘Yeah! Try that here in Texas!’

I came around to the realization that there is not a clear juxtaposition of “special vs not” but rather a wide swath of existing structures, all of which have real value and immense potential.

Therefore, the “opposing” example is a special project in East Austin. While this project did not reuse the entire building, the design team reclaimed the existing concrete slab, which embodies most of the carbon in an existing structure and reused several key items such as the above ground water cisterns. They also recycled the existing steel. The design team went so far beyond high-performance and connection to the neighborhood, I simply had to share.

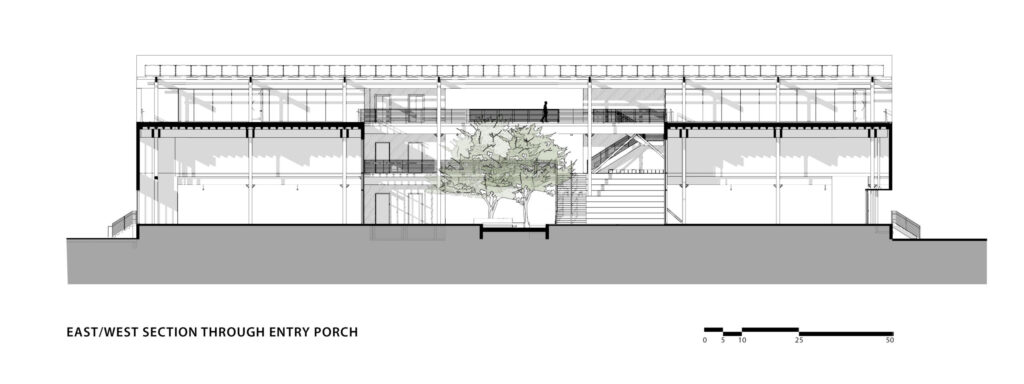

As architects and designers, we are accustomed to projects that start with strict requirements and boundaries. For the Fifth + Tillery Project in East Austin, the site came with existing land limitations and the team was immediately limited to the footprint of the existing warehouse and therefore the site was reimagined as a vibrant indoor / outdoor creative office building. The building was originally used as a distribution warehouse and was later converted into a creative maker space. Marking the transition from neighborhood to industrial district, the project draws inspiration from its contracting surroundings, and with a focus on sustainability, wellbeing, and community, “Fifth + Tillery turns a traditional office building inside out.”

In an interview with Michael Waddell, design director with Gensler, he explained, “when we first met the client on site to look at the existing warehouse, the main concern that kept coming up was how much impervious cover was on site…Initially, we talked about how to re-green the site and introduce meaningful landscape into the footprint. We decided to create a creative office space, incrementally making decisions based on sustainability, wellness, and workplace experience.”

The existing foundation was reused and the design team worked early on with “daylighting studies to right size lease depths to optimize daylight and minimize the need for artificial lighting. (They) introduced an L shape cut down the center of the steel structure.” The “sweet spot” was an 80’ wide depth in which natural daylight could come in from the punched windows around the exterior and the full height window walls on the shaded interior courtyard sides. This simple move allowed for ‘the massing to respond to daylight, predominant breezes…while also pulling in greenery.’

“With the forest-like approach, we created a cost-effective kit of structural parts, with a hybrid timber system of steel columns and long span glulams establishing a repeatable system that also results in a beautiful backdrop to the landscape within the building” Waddell continued, “In lieu of a traditional lobby, the one at Fifth + Tillery is an open plaza filled with trees and landscaping.

There is no multi-tenant corridor connecting tenant spaces, but instead, an open courtyard carves through the building, with open stairs and walkways connecting spaces and levels. There’s fresh air, nature, breezes, water, and the warmth of timber that creates this amazing space for people to come together.”

The original warehouse offered little aesthetic inspiration; the design team was instead inspired by the tangible outcomes of biophilic design. The benefits “are proven to increase happiness, concentration, and performance, all while decreasing absenteeism within the workplace. The research inspired us to build off that biophilic approach, with an idea of creating a forest-like building.”

With that in mind, the design architects worked closely with the landscape architects at Campbell to create a rain garden within the courtyard while using predictive modeling for water and energy. Additionally, they re-used three 10,000-gallon cisterns already on site “for irrigating the landscaping and supplying water for the central water feature that runs throughout the courtyard and a new shade structure, incorporating solar panel was sized to generate an annual production of 688,688 kWh, with peak summer production generating 90%+ of the expected demand. The modeling also predicted an expected payback on the system of 4.3 years, but with pre-pandemic utility rates. I would expect the payback to be sooner now.”

A tell-tale sign of high design, the Fifth + Tillery can easily point to all ten measures of the AIA’s Framework for Design Excellence. To highlight just two of them:

- “Design for Economy” focuses on material reuse, right sizing the space, and incorporating exterior walkways to reduce operational costs. The project incorporates these principles, while also “maintaining a cost-effective approach to construction. All these strategies add value to the owners, occupants, and community while reducing the embodied and operational carbon footprint of the project.”

- “Design for Wellbeing” focuses on the physical ideals for a healthy body, such as natural light, thermal comfort, movement, and indoor air quality. With the prioritization of biophilic design, in which they brought in wood glue lam beams, natural plantings and a minimalist and enticing white large social staircase that promotes active design and can also function as an auditorium for community events.

“The greenest building… is the one that is already built.”

Carl Elefante, FAIA, LEED AP

I believe most of us know the greenest building is the one that is already built. We know this so intuitively that we rarely stop to question it, or more importantly, stop to measure it. Fifth + Tillery, as well as Hotel 1928, are both beautiful in many ways, it is easy to overlook the embodied carbon that was saved by reusing the structure.

Designers have access to numerous resources for measuring and reducing embodied carbon in buildings, highlighted below. Key references include AIA’s Blueprint for Better on Embodied Carbon and their white paper on Building Reuse. Use tools like the CARE tool for building assessments and or the EC3 calculator for material specifications.

Whether restoring historic landmarks or reimagining mundane structures, every building has value. It is our responsibility to evaluate options, assess embodied carbon, and leverage inherent assets to create solutions that meet project goals with beauty and functionality. The main thing is to start. Just start.