Code Stories

Credit: Huckabee

Credit: Huckabee

It’s 12:36 p.m. at Lakeview Elementary School and Mrs. Burrell has settled her third-grade students into their math exercises on equivalent fractions. Recess was inside today because the weather is turning as dark clouds roll by in the sky.

Suddenly there’s an announcement over the intercom of a weather emergency, instructing teachers to begin their sheltering protocols. The students leave their desks and line up facing the door. They’ve practiced this before, so there isn’t much alarm in their faces. But Susie asks, “Is there a tornado?” The teacher calmly responds, “No sweetie, it’s just a drill. Everything is fine.”

They head into the corridor to their designated location and take a seat on the floor with the other children. A low chatter fills the space while they amuse themselves as the teachers cluster together and whisper. Checking their phones, the teachers learn this isn’t a drill. Mrs. Burrell suddenly wonders: “Why are we in this corridor? Will this protect us from the tornado? How can this possibly protect us? Why doesn’t this school have a tornado shelter?” The sounds of laughter and little conversations fade as the wind roars and the rain pounds. Suddenly, the power goes out.

These drills are common in schools throughout Tornado Alley, where funnel clouds can pop up quickly and devastatingly. But the requirement for schools to have tornado shelters is relatively new. The 2015 International Building Code (IBC) was the first model building code to require storm shelters in schools. Any new school within the 250 mph wind speed map is now required to have a storm shelter constructed in accordance with the ICC 500 Standard for Design and Construction of Storm Shelters.

The 250 mph zone affects 23 states. There are 31 states within the 200 mph zone, although no requirements for shelters outside the 250 mph line. There are nearly 100,000 public schools in the U.S., a good number falling within the 250 mph zone and most of which do not have tornado shelters.

In Texas, this zone cuts through Waco, east to the state border and north through all but the very western edge of the Panhandle. On average, Texas experiences 155 tornadoes per year, more than Oklahoma, Arkansas and Louisiana combined. Since 1950, the state has seen nearly 8,700 tornadoes, as tracked by the Tornado History Project. Of that total, six were EF5s – the worst – and 48 were EF4s. The state’s deadliest tornado was an EF5 that tore through Waco, killing 114 people in 1953.

The Dallas-Fort Worth area has seen many tornadoes over the years. In December 2015, a storm system tracked from coast to coast generated 32 tornadoes, resulting in 59 fatalities and $1.2 billion in damage from New Mexico to Maine. In Dallas County, an EF4 spun out by the system the day after Christmas killed 13 and damaged 22 businesses and nearly 600 homes, almost 400 of them destroyed.

In October 2019, an EF3 tornado ripped through University Park in the Dallas area before crossing Interstate 635 and blazing a trail through neighboring Richardson and Garland. It’s the costliest tornado in Texas history at $1.55 billion. By no small miracle, no one died.

ICC 500-2020 recently published an update from 2014 that is now adopted in the 2021 IBC. The purpose of this standard is to establish minimum requirements to safeguard the public health, safety, and general welfare relative to the design, construction, and installation of storm shelters built for protection from tornadoes, hurricanes, and other severe windstorms. Any storm shelter that is meant for residential or community use for tornadoes or hurricanes must comply with this standard.

The Federal Emergency Management Association recently published the fourth edition of the P-361 (2021) Safe Rooms for Tornadoes and Hurricanes, the federal guidance and criteria on designing and constructing a safe room that provides near-absolute protection from wind and wind-borne debris.

FEMA P-361 includes emergency management considerations and risk assessment guidance that go beyond the scope of ICC 500. P-361 says: “Storm shelters provide life safety protection from extreme wind events; they are designed and constructed to meet ICC 500 criteria, but do not have to meet the additional funding criteria” in FEMA P-361 to be considered a safe room. All safe rooms are storm shelters, but not all storm shelters are safe rooms.” If a shelter is funded by FEMA, it has to meet the additional criteria of FEMA P-361.

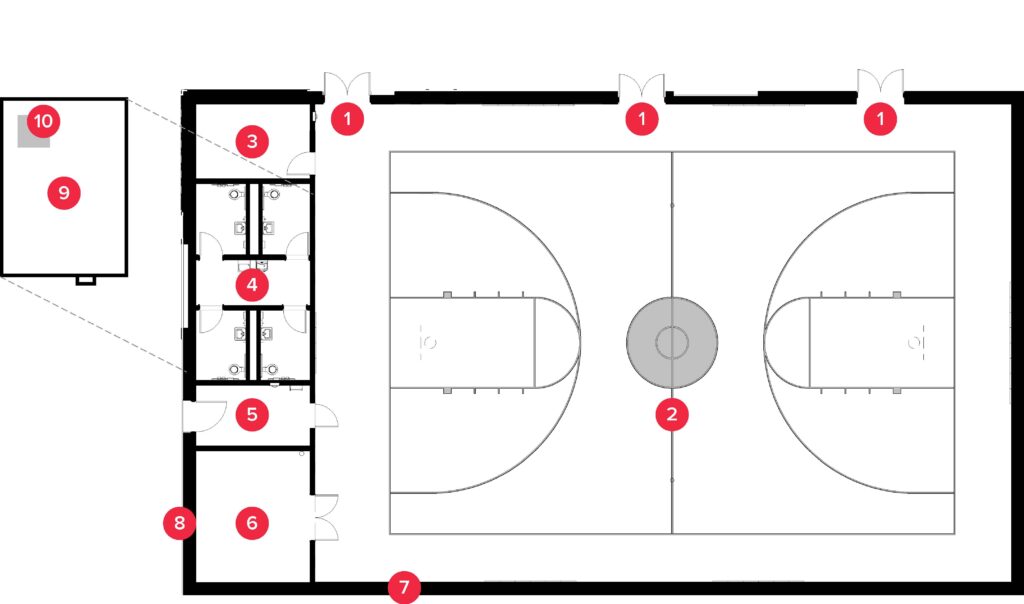

Tornado shelters in schools are typically constructed as a room or space normally used for other purposes, such as a classroom or a gym. The ICC 500 requires that there be 5 square feet per occupant. An elementary school that has 800 students and staff on a typical school day would require at least 4,000 square feet of usable floor area, not counting space for furnishings such as desks.

Elementary School: Currently the gymnasium storm shelter at 6,500 square feet can accommodate 1,000 occupants. The green is the additional area needed for the storm shelter to be 20,000 square feet if it had to be designed for the fire egress occupant load of this building, which is 2,600 people with a 35% reduction factor.

“It is not the intent of ICC 500 or FEMA to require the storm shelter or safe room to be designed to accommodate the total occupant load of the host building, which is much greater than the actual number of host building occupants at any given time. The total host building occupant load — based on fire exiting considerations — includes occupant loads for all host building spaces simultaneously and is used to determine the required means of egress for normal use. As a result, the total occupant load for the building would be excessive for storm shelter or safe room design capacity, which should be based on the number of intended occupants to be protected. Once the number of intended safe room occupants is decided, the density table is used for determining the minimum usable floor area,” FEMA P-361 says.

Two significant updates occurred in the 2020 publication affecting how capacity is determined.

- The definition for “Storm Shelter Occupant Load” was deleted, and the definition “Design Occupant Capacity” was added. Design occupant capacity is defined as “the number of occupants for which the storm shelter is designed.” Associated language throughout the standard was updated, and correlating language has been approved for the 2024 IBC. This was done in part to distinguish between setting a maximum occupant load for a space versus determining a minimum design occupant capacity for a storm shelter, which was initiated in the 2018 IBC.

- Understand that the ICC 500 applies to all kinds of storm shelters, including community and residential, tornado, and hurricane. It does not delineate any requirements between a storm shelter that serves a fire station, a public library, a large multifamily housing development or a school. Section 502 clarified that the design occupant capacity is either assigned or calculated. For example, the owner of a recreation center could either determine the size of the shelter and number of occupants served by two methods:

- Assigned: Either saying how big the shelter needs to be to serve a certain number of people, then sizing the shelter accordingly.

- Calculated: The exercise rooms combined are planned to be X square feet. Therefore if we make the shelter that size, it can serve X number of occupants.

The designer and the owner decide the assigned design occupant capacity. There are no other stipulations, minimums or maximums.

School districts will not only need to consider the size, but also the location and cost of storm shelters for new facilities and additions. School construction costs in general are on the rise. Schools are larger, more open, and packed with technology and specialized areas like science labs, fine arts, and athletics. That’s not to mention material costs are rising and a continuing skilled labor shortage. In Texas, costs vary greatly by region, with Dallas-Fort Worth and surrounding areas within the 250 mph wind speed map the most affected by the storm shelter premium.

The aftermath of COVID-19 has also put health and wellness on par with safety and security for schools. The design of vestibules has changed over the past 10 years; now the design of toilet rooms and mechanical systems seeks to reduce touch points and air particle transfer. Initial heating/cooling and insulation construction costs have increased with energy code requirements. On the other hand, buildings are more sustainable, resilient, and efficient, which decrease operating and life cycle costs.

Codes will continue to change and costs will fluctuate, but storm shelters are now an integral part of many schools. School districts and their designers will adapt to whatever threats or challenges arise. There will be innovations and efficiencies. Although driven by words like “faster,” “easier,” “lighter,” “cheaper,” the reality is that society tends to be reactionary. It takes disasters like Moore, Oklahoma, in 2013 and Joplin, Missouri, in 2011 to move us forward.